The world of pop and rock music has been rocked by a series of non-events as of late. Woodstock 50 collapsed in on itself in an almost unbelievably boring, sub-Fyre-Festival fashion. Paul McCartney — by many accounts the greatest living pop musician — launched an aspirationally viral video “challenge” that was met with a collective shrug. A band that sounds exactly like Led Zeppelin won a Grammy, while Jimmy Page is holed up in his castle, allegedly working on music that he may never get around to releasing. As the 2010s draw to a close, it feels more and more like there’s a law of entropy at work in the music world: all an artist’s creative energy concentrates in the beginning, and then disperses over time, never to be recovered. Nostalgia tours, holograms, collaborations with younger artists — these all increasingly seem less like marketing ploys and more like attempts to construct a sort of Maxwell’s Demon to reverse the inevitable evacuation of artistic inspiration.

Simon Reynolds, writing in 2011, called this phenomenon “retromania,” or “pop culture’s addiction to its own past.” There’s an important, often overlooked corollary to retromania, though: the lack of late-career masterpieces in pop and rock. In fact, “name a late-career masterpiece” is probably one of the most frustrating exercises you can undertake as a fan of post-1950 popular music. Maybe a few come to mind: Johnny Cash’s covers albums, Bob Dylan’s “Love and Theft” (2001), the Robert Plant and Alison Krauss record, Leonard Cohen’s “You Want It Darker” (2016), the last dispatch from Bowie. Probably also Van Morrison’s “Enlightenment” (1990), maybe Jay-Z’s “4:44” (2017), and almost definitely Kate Bush’s “50 Words for Snow” (2011). This tier quickly exhausts itself, though, and then you find yourself in the murkier territory of comebacks, revivals, rebrandings, and retreads, very few of which get much acclaim, regardless of how much they sell or stream. After this second tier, things run dry.

And yet, in nearly every other form of artistic production, there is no shortage of late-career triumphs. Robert Christgau, the self-appointed “dean of American rock critics,” hinted at this when he wrote that Dylan’s “Modern Times” (2006) “radiates the observant calm of old masters who have seen enough life to be ready for anything — Yeats, Matisse, Sonny Rollins.” Sonny Rollins made urgent and sophisticated music right up to the end of his performing career, and Matisse and Yeats did some of their most enduring work in their final years. Henry James’s late novels are infamously love-it-or-hate-it among readers, but their dense, claustrophobia-inducingly inward style had an undeniable influence on literary modernism and everything that’s followed it. Toni Morrison arguably passed away at the top of her game, writing masterworks of both fiction and criticism in her last decade.

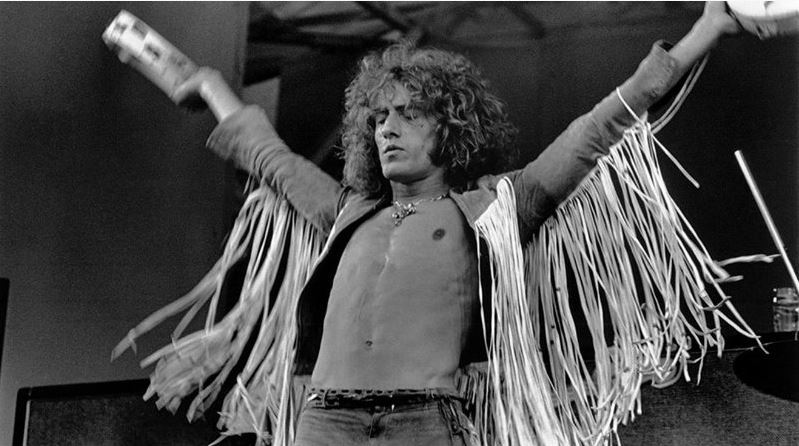

If there are plenty of late-career masterpieces in literature, the visual arts, and even jazz, why are there so few in rock and pop? One place to look would be the cult of youth that has been so crucial to rock since the early days of high school party songs and requiems for “teen angels” who died in tragic car accidents. From the start, rock and roll was at least nominally about young people, their messy vitality and surprising complexity. Roger Daltrey’s 1965 rallying cry “Hope I die before I get old” only spelled out the impulse that was there from the beginning. Of course, the trouble is Daltrey did get old, and along with many others from his generation, continued to make music, to ever-diminishing critical acclaim and fan excitement. (Who would put “Eminence Front” in their top ten Who songs?)

Through the lens of rock’s youth cult, this near-universal downward trajectory looks like a simple loss of energy. Artists grow old, mellow out, lose touch with the spirit of the times, and their audiences gradually tune out. That’s the subjective side of it. The objective side is: pop music, born in the midst of a youth-culture revolution that was really a consumer revolution, is more subject to market forces than most fine art. Sounds go obsolete fast, even if they’re inevitably exhumed for a revival a few years down the line. As they age, rock and pop artists are faced with three options, none of them easy. They can keep making the same kind of music they made early in their career (call it the AC/DC route), they can chase the changing trends (the Rod Stewart route), or they can turn inward, making ever more idiosyncratic music that tries to sever itself both from their past work and the fashions of the day (Bjork, Radiohead). No matter which path an artist chooses, though, we can’t help but read the agony of this decision into their late work. We’ve seen too many rock docs, too many episodes of Behind the Music, not to feel the combined pressure of market and creative forces on late-career artists. The subjective and objective sides of the problem end up meeting: whether we see late work as a struggle against waning artistic power or a fight to retain a niche in the market, we experience the late work not as art, but as a document of the artist’s failing strength. We use the word “masterpiece” for those late works where we feel the artist has triumphed over these forces and managed, against all odds, to realize her individual vision.

Theodor Adorno attacks exactly this kind of interpretation in his short essay “Late Style in Beethoven.” He points out that when we talk about an artist’s late style we have a tendency to relate everything about that style to biographical factors in the artist’s life. According to this line of thinking, which Adorno calls the “psychological interpretation,” late works are often taken as evidence of impending death. They’re documents of death’s gradual intrusion into the creator’s life, like a death mask fitted while the body’s still warm. Adorno, granted, was a notorious opponent of pop and rock music — despite the far-right conspiracy theory alleging that he wrote the Beatles’ entire oeuvre. Still, the critical reception of Leonard Cohen’s “You Want It Darker,” the last album he released before he died, is a case in point for this particular theory of his. One reviewer notes how the album starts with “a nanosecond’s rush of labored air” from an audibly frail Cohen, setting the tone for nine songs’ worth of “Confronting Mortality at Close Proximity.” Around the same time, director Francis Whatley voiced his frustration with critics’ efforts to make Bowie’s last album fit with the psychological interpretation: ”People are so desperate for ‘Blackstar’ [2016] to be this parting gift that Bowie made for the world when he knew he was dying but I think it’s simplistic to think that. There is more ambiguity there than people want to acknowledge.” Of course, not all late work is done by artists who are on the verge of death, and not all artists’ last recordings even get the dignity of the psychological interpretation. No one reads the pathos of Malcolm Young’s coming illness into AC/DC’s “Black Ice” (2008). Still, the preoccupation with death, whether physical or a more metaporical “death of the muse,” speaks to our more general tendency to take late work as a mere biographical document.

Instead of getting caught up in this biographical reductionism, Adorno challenges us to focus on them as works of art. “Touched by death,” he writes, “the hand of the master sets free the masses of material that he used to form; its tears and fissures, witnesses to the finite powerlessness of the I confronted with Being, are its final work.” As the artist faces down her own mortality — or, as the case may be, the market’s turbulence — she is unable (or stops trying) to shape her medium according to her own idiosyncratic “vision.” Her material, left to its own devices, takes on an uncanny life of its own. This is why, as Adorno sees it, the moments of transcendent “polyphony” in Beethoven’s very late work are often interrupted by stray conventional phrases and ornaments, wandering clichés that have more to do with the materiality of music itself than the composer’s grand artistic vision. For Adorno, this is what’s so arresting about late style: rather than the artist’s individuality, the clash between carefully executed sections and patches of raw untamed medium expresses something universal about the “mythological nature of the created being and its fall.”

However you feel about the high Biblical drama of this last twist in Adorno’s argument, it seems right that later works across mediums tend to be more impressionistic — that is, works that are to some extent about their own medium, that let seemingly unworked-on, not quite representational bits of pure material have their own way. Plenty of late works in rock and pop take this sort of impressionistic turn. Dylan’s albums since “Love and Theft” have been exercises in letting the smallest intelligible particles from the blues, rock, and literary traditions collide and assemble into new forms. Segments of Parchman Farm work songs sit side by side with fragments of Confederate poetry; Charley Patton lines, Emily Brontë characters, and bits of surf-rock kitsch are mashed together but never fully incorporated, like lumps of flour in undermixed batter. Aretha Franklin’s “A Rose Is Still a Rose” (1998) interpolates jazz scat singing, contemporary R&B productions from none less than Lauryn Hill, and free-floating splinters of adult-contemporary pop tunes — see the title track, which features Aretha singing a strain of Edie Brickell’s “What I Am” in the background. After a string of tepidly received solo albums, Paul Westerberg of the Replacements released “49:00” (2008), a 43-minute sound collage where songs fade in and out of each other, recreating the experience of multiple radio stations fighting for primacy as you drive from city to city. Near the end of “49:00,” as a wistful song about “rock and roll battles” winds down, a medley of classic rock covers breaks in, tripping all over itself until it resolves into a sustained, earnest take on the Partridge Family’s “I Think I Love You.” It’s not quite sampling, which usually either obscures the origin of the sample by blending it seamlessly with the rest of the composition or serves as a winking reference for those in the know. It’s more that, in all these late-career triumphs, the artist and the material itself take turns running the show. While all these artists’ early work feels like an assertion of a totally individual vision (think of how authoritative Aretha’s “Respect” is), here there’s a thrilling oscillation between controlled self-expression and something like automatic writing, where phrases, melodies, and tropes from pop history come spilling out seemingly unbidden from our collective musical unconscious. We can only appreciate the richness and weirdness of this internal conflict if we abandon the psychological interpretation.

Ultimately, the label “masterpiece” has more to do with the conventions of criticism than the qualities of the work being criticized. Even in the age of poptimism, where criticism has absorbed elements of fandom and fandom has taken over much of criticism’s duties, there’s still a certain critical template for what constitutes a masterpiece. We’re looking for bold assertions of individual talent — of “vision” — that are either right in step with the spirit of the times or, preferably, ahead of it. So many late-career works fail to meet these criteria. “Love and Theft” has clinched the honor, but “49:00” remains something of a cult object, and “A Rose Is Still a Rose” has somehow slipped through the cracks of the nostalgia-industrial complex. We have an equally set template for what constitutes a failure, especially a late-career failure. Late-career duds fail to “say anything new” when their creators sound like they’re tapped out, out of step with the market, losing the struggle for relevance. Masterpiece or failure, our extreme judgments frame pop music as a strictly individual achievement, as if the artist is reinventing the entire tradition from scratch with each album. But if we listen closely, late work in pop blows up this assumption. Records like Franklin’s and Westerberg’s aren’t examples of artists triumphantly, or even successfully, expressing themselves. They’re also not just documents of their creators’ fading vitality. Strangely enough, it’s exactly their failure — their reliance on tropes, clichés, bits of unworked material from different traditions — that takes them from a purely personal place to somewhere collective, even historical. The pleasure of these records is listening to pop play itself on a level far beyond the individual.