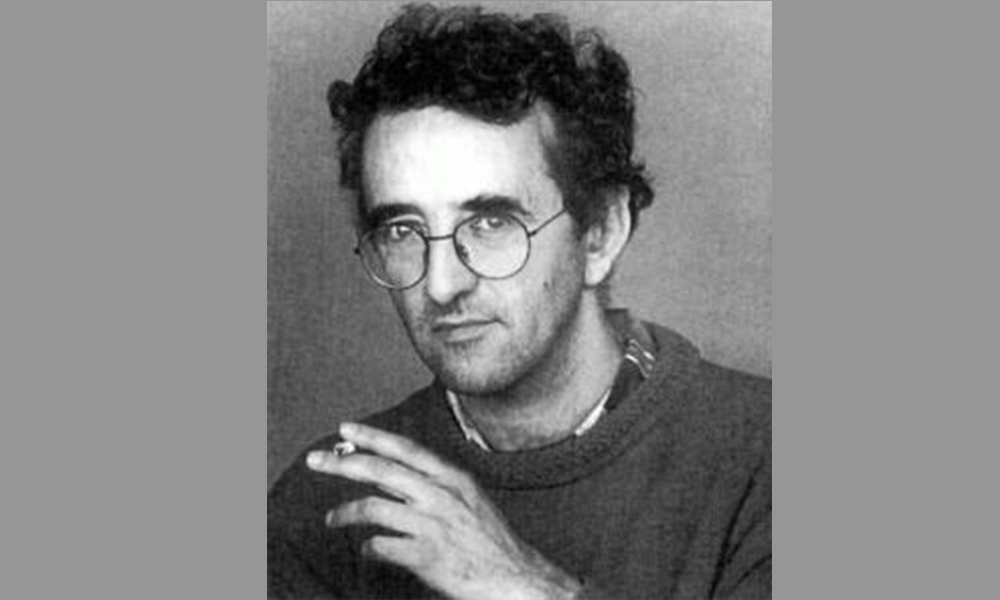

I read recently that Roberto Bolaño, who was from both Chile and Mexico, felt that because he was a child of both, he was a child of no nation. I very much relate to this idea, though I am, I would guess, more American than he was Mexican. He immigrated as a youth while I was born and raised in the United States, and in this multi-cultural era, all of us — of all faces, all tones — are called American.

I was drawn to Bolaño’s feeling of nationlessness. I love my mother’s culture in the Philippines: the warm lessons I learned from it, my sweet aunts and uncles, my most darling cousins, the friends who believe foremost in friendship (and puns). And yet, because it is an absolute foreignness to the country where I sit and type, there is a disjunction. By accent, by knowledge of sit-coms and mid-eighties radio, and foremost by law, I am an American citizen. But there is something that presses to the side. I am even more lost and groping in my mother’s country. I know only words and phrases in her language, only one sit-com, no mid-eighties radio. I wonder if this inability to look back through my ancestors, through to Ireland and the Philippines (but more the Philippines; mixed people are not white in our history) is something like being adopted, a feeling of the severing of the threads of time. My grandparents, sure, but my islands? They wouldn’t know me.

There is isolation in this, and there is beauty, too. There is a freedom. I feel allowed — even if slightly — to feel connected to so many places on earth. But then, in the introduction to Savage Detectives, after Bolaño expresses that he is a foreigner wherever he goes, he says that his “homeland is the Spanish language.” And I was jealous of this. I set the book down and blinked.

I am not a child of the English language. I identify more with the mestizo nations of Latin America, though I speak Spanish neither natively nor fluently. Spanish speakers of the Americas have always claimed me as much as Filipinos have because mestizo is what they understand themselves to be. When I tell them, they point at my eyes and say, “Oh that’s why you have eyes like that.” And I like that; it’s calling my experience natural, something they’ve seen before through their own almond eyes. I suspect it’s what my fellow citizens want to say but don’t. Carlos Fuentes wrote that Luisa Valenzuela has a “baroque crown, but her feet are naked;” this is what he meant.

¤

And so I had to think, if I’m not a child of the English language, what am I? Is there something I can crystallize, that belongs to the history of the world? English is not mine, though I revel in it. Spain colonized us (but not “us”) too, but Spanish is not mine. Tagalog (Filipino) is both the Mother Tongue and a great mystery.

Eventually, it came to me: I am the child of miscegenation. This is not a great word. It sounds like a scientific experiment. We also say “bi-racial,” but that doesn’t sound good either. There should be something more poetic. I like the idea of a Creole, which has meant, at various points, Africans born in the Americas, Europeans born in the colonies, mixed-race people in general, or a bastardized version of a (usually) European language spoken (usually) by conquered peoples. I relate to its disjointedness, its birth in the “New World”: a word for children of the New. And by this, I don’t mean Europe’s next branch, but I mean the whole new thing born of the apocalypse, holocaust, and beauty that was the birth of the Americas. But Creole is also not quite right.

So let me attempt the poetic. Of all the nations in this hemisphere, all but three would admit themselves the children of miscegenation, literally and/or figuratively. These countries are in a ridiculous amount of denial. I am in good company in my history as the child of maritime advances, in the company of the almond, hazel-eyed bastards of rapists and wayward winds. In the Philippines, they call me a mestiza, but artists and intellectuals find this pretentious. It’s a way people of old money assert their white blood. In the Americas, people use the word to claim their indigenous blood.

A Dominican-American woman I once met — very assimilated, WASPy, summers on the Long Island, school years in the Northeast, prep-school, Amherst — told me that just looking at me she could tell I was “displaced.” It hurt a little bit to hear that, like I was marked. But I liked it too, a succinct word for my experience. This woman, who had gone down a very different route from mine, still identified the not-quite-being-like-anyone-else feeling, the yank from time, the rip from the continuum.

People continually argue with me about what color I am. When people say I look white, they sound irritated with my more complicated explanation. But just as often, or perhaps more so, onlookers insist they’d never call me white. It makes no difference the race of the onlooker; I’ve heard it from all sides. But I think whites and people of color get mad for different reasons: whites because I should want to be white; black, brown, and yellow people because I shouldn’t complicate the color line so much, as I may receive white privilege. Recently, an old friend and her new boyfriend, both black — she American, he a Londoner of Nigerian descent — argued with each other about how to perceive me. He insisted I was white. She said she would never call me white. They asked each other, how could you think that? Welcome to me.

This fascination with the color line, the place I live, has led to my project, 1850, an episodic series based in New Orleans before the Civil War. Because of mismatched demographics (many more white men than women, many more free women of color than men), and because of Louisiana’s unique history of large amounts of free people of color (enhanced by refugees from the Haitian Revolution), there were many mixed couples in their history, some part consensual, some part love, some part coercion, and of course, the unutterable sexual violence of slavery contributed to this phenomenon. The city’s records are full of tales that fascinate me: passing, inheritance tussles between white and bi-racial half-siblings, and court battles over racial definition (including a few about whether people had African or “Malay” ancestry). I came to this subject matter after years of difficulty deciding about whom I should write, what color characters I have the right to create. Then it came to me one day, mixed people.

Sharing this doesn’t feel as grand and eloquent as I’d hoped, but it feels pretty good. I feel like I am telling some truth I’ve fought long and hard to discover, hidden in plain sight. Hidden in plain sight is the history of the Western Hemisphere.

¤

And what of my hemisphere? For I am a child of the Western Hemisphere more than the United States. Let me go to a simple trope of American culture: Elvis. He wasn’t fully white, but he was “the King.” I won’t debate the source of his music here, but I will say a forbidden truth outright: the rhythms of this country are African. And Elvis became a symbol of the United States’ contribution to world culture, an aesthetic that has traveled the globe via messengers like Charlie Parker or Mick Jagger: cool, the province of the anti-hero, the underdog. I can’t help thinking this has something to do with the ideas of democracy (that Jagger is American makes no difference he sings estadounidense music). That this position as the underdog is so often performed, a fantasy of being both king and cunning serf, is again a whole other monster. We are an empire wishing to be an underdog, jealous of the underdog.

There was a second musician we called the King whose race-switching was also at the center of his identity, Michael Jackson. Charles Mann, in his great history of the pre-Colombian Americas, 1491, credits Native Americans with the spread of democracy. He was not the originator of this idea. Benjamin Franklin, who wrote with some respect of the indigenous cultures around him, might have admitted it himself. But Mann’s articulation of these ideas is deft. Our world is deeply rooted in the collision of cultures and continents begun in the colonial error. We are the bastards of wayward winds, of the terror and glory that cannot be undone.