In August of 1987, my parents, my older sister and I drove from Riverton, Utah to the Grand Canyon. U2’s The Joshua Tree had come out in March. It was one of only two albums we had in the car with us. The other was Paul Simon’s Graceland, released exactly one year earlier. My sister, who, at 15, epitomized New Wave, with multi-hued, brow-high eyeshadow and sky-high winged bangs, insisted on U2 over Simon, always concerned with her cool-factor. In our white 1984 Toyota Tercel, we turned the cassette tape over and over again, listening to it repeatedly.

I have scaled these city walls / Only to be with you

But I still haven’t found / What I’m looking for

At eight years old, I didn’t understand many of the lyrics. What was he looking for? I pictured a man on hands and knees peering under the bed.

We drove first to Phoenix, spending four days at a resort called The Pointe, where my dad had stayed a few months earlier for a Postal Mail Handlers Union conference. We were a family of humble means. All I knew of vacations then was camping and single-story roadside motels. The Pointe, with an oasis-style outdoor pool, palm trees, a waterfall, three stories of pool-facing rooms, a recreation center and an arcade, was the fanciest place I’d ever been.

I made a friend named Rainier, from Quebec. She had a funny accent. We played with My Little Ponies in the pool. In her white bikini, my sister sunbathed until her skin turned mahogany. Then she went on a date with the lifeguard, whose skin was the shade of walnut, and she spent the next two days down-dressing, trying to appear as unattractive as possible. I tried to look sexy in my child’s safari print one-piece.

I cried when I had to say goodbye to Rainier. Quebec sounded so far away; I knew I’d never see her again. At eight years old, when the magnitude of the world is just beginning to take shape, and the concept of time past is new, this realization lingered for the rest of the trip, and returned with each letter I received from her over the next year, until we stopped writing, and the brief friendship faded once and for all.

I’m still waiting — I’m hanging on / You’re all that’s left to hold on to

On the drive to the Grand Canyon, my parents commented on every motor home we passed: “Too big.” “What kind of gas mileage you think that gets?” “Oh, now that one’s just perfect.” At parking lots and rest stops, they’d ask the owners of the RV’s if they could look inside. My sister would be embarrassed; I’d be curious. I’d peek inside and daydream about what it would be like if we had one.

We counted state license plates along the way. Look! Nebraska. Hey, there’s Utah!

Outside, is America / Outside, is America / America

I asked my sister how to look cool for boys and she taught me some poses, which I practiced in the pictures we took at Mather Point. I was a goofy-looking kid, with buck-teeth that jutted so far in different directions I could stick my pinky finger between them. I felt different, like a weirdo. I became an observer, watching others be cool, be cute, be popular. Outside was America, where all the pretty people lived. I loved looking at it, and wanted to be a part of it. When I returned to school that fall, I practiced the same poses on the playground, trying to impress Joey Maio, Sam Stevens, Justin Kenworthy. As I grew, and got braces, and my features filled out, I didn’t have to try so hard to look like everyone else, and yet I’ve always felt removed. Outside is America.

When we all needed a break from U2, my sister and I sang the songs she’d learned at camp earlier that summer. I’m in love with a big blue frog, and a big blue frog loves me. My mother bought us bubblegum at a gas station, so that we’d shut up. We kept singing so that she’d give us more gum. Then we turned U2 back on.

I wanna run, I want to hide / I wanna tear down the walls / That hold me inside

We stayed in a blue cabin. My parents went out to dinner and left us behind. We played charades — I’d never played before and felt like I was being invited to a big kid’s game. It was Leah’s turn, and she kept pointing at the clock. “Time!” I called. She pointed like I was right, but then she continued pointing at the clock and making like she was rewinding it. “Rewind time.” “Backwards.” “Over and over again.” “Slo-mo,” I guessed. She got so frustrated she threw herself on the bed, and then on the floor, and then over a chair. “Time After Time!” she shouted. The Cyndi Lauper song. I felt so dumb.

Then I floated out of here, singing / Ah la la la de day / Ah la la la de day

At a roadside overlook, Leah refused to get out of the car. An argument had been percolating between her and our mom all day, and she’d gone completely silent. Instead of poking at me or singing or trapping me into saying bad words, she sat strapped into her side of the car, looking out the window. I wandered the site alone, looking at the graffiti scrawled and scratched on the rocks and railings. “Joel was here, 1985.” “Sandy + Tom 1981.” One of them said “Leah 1978.” My sister’s name, my birth year. I was sad she wasn’t seeing it with me. I told her about it when I got back to the car, but she just shrugged her shoulders.

When Bono sang the lyrics “bullet the blue sky,” I couldn’t fathom why he would want to. The sky was beautiful.

I wanna feel sunlight on my face / I see the dust-cloud / Disappear without a trace

I turned nine on August 27. My parents gave me a fuzzy Garfield birthday card and said I could pick out anything I wanted from the Grand Canyon gift shop. I chose a souvenir that had three rows of gemstones with googly-eyes glued onto a cassette-sized plaque that said, “Rock Band.”

I was fully conscious then of feeling happy. I felt the sunlight on my face. I knew I was who my family loved most in the world, and I loved them with everything in me. But I felt that we were changing, time was moving forward, and there was nothing I could do to stop it. Soon, we’d be back at home, my parents working graveyard shifts at the post office, my sister in high school, finding boyfriends instead of playing with me. I wanted us to stay inside this collection of happy moments forever, like a band of gemstones glued against a moving backdrop of the canyons of Utah, Nevada, and Arizona, set to the soundtrack of Bono singing about America.

I have climbed the highest mountains / I have run through the fields / Only to be with you

Six months later, my sister’s father (we’re technically half-sisters, but never define ourselves that way) died suddenly. I woke one morning to the sound of my sister shouting. I wandered out to the living room where I saw my parents standing on opposite sides of the room, my sister between them. She wouldn’t let them near her. Upon seeing me, she escaped to her room. My father sat me down on our faux-suede, olive green couch and told me the news.

The following year, Leah would move out after a shattering argument with our mother. I remember them standing in Leah’s bedroom yelling at each other. I stood in the hallway, like I normally did, telling them to stop fighting, until they yelled at me to go to my room. I heard Leah storm out, the front door slamming behind her. I heard her say she wasn’t coming back.

We would never be the same as we were that summer of The Joshua Tree.

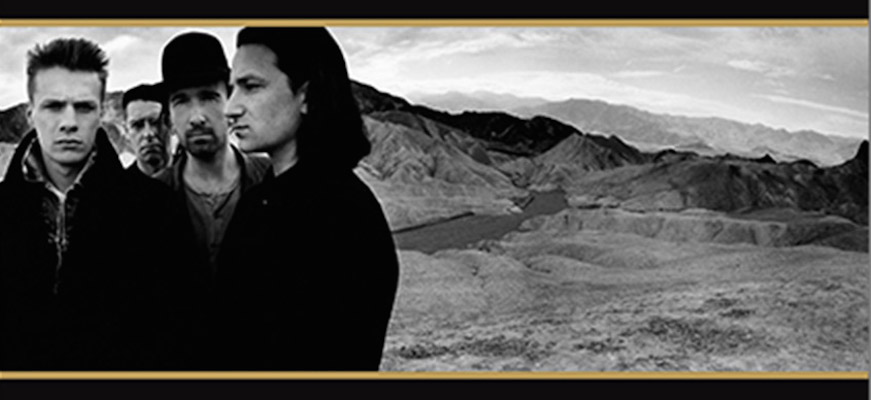

In March of 2017, Bono told NPR’s Steve Inskeep of the band’s inspiration for the album. “We were obsessed by America at the time,” he said.

The songs those young Irish musicians wrote to capture what they imagined was the essence of America became the soundtrack for my family’s most cohesive time together. Throughout my life to the present day, across all the places I’ve been — so much further away from home than Quebec, I never could have guessed — when I hear that album or any piece of it, I feel the Arizona heat, see my parents in the front seat, my sister beside me, immense red canyons passing as we drive, the precious now becoming a memory. “We think America is an idea that belongs to people who need it most,” Bono said.

For the 30th anniversary, U2 launched The Joshua Tree Tour, playing the album in its entirety at every show. I bought a ticket for The Rose Bowl in Pasadena — I’d never seen them live. As Bono sang the songs that I know better than my own memories, vast desert landscapes extended behind him in projections, rolling red canyons stretched above him. The band performed against imagery of that summer, my summer, the summer that belongs to my family. I hadn’t known that the associations I have with their music, formed by the scenes of my childhood, had been at the crux of their creative intention. I hadn’t known. I hadn’t known that inside, was America. We were America.

And when I go there / I go there with you / (It’s all I can do).