Last month, the Turkish Statistical Institute announced that the number of public library memberships in Turkey increased by 24.1 percent in 2016, compared to the previous year. In a time of terror, political uncertainty, and a coup attempt, Turks took refuge in libraries.

Some Istanbul libraries owe their existence to taxes; others to banks; one to an English monarch. SALT is located in the previous headquarters of the Ottoman Bank, which was founded in 1856 on the orders of Queen Victoria, a friend of the westernizing Sultan Abdulmecid. The building opened at a time when Turkish-British commercial ties were at their peak. Today, its library houses 110,000 books. Last year, it served more than 47,000 readers.

On a recent weekday the library was bustling with bright-eyed readers, and every seat were occupied. A hush fell over after I entered the reading room. On a desk by the entrance, a young man pored over a book; he checked a page number, and he typed a footnote to his thesis; in the little garden outside, two young girls smoked rollies. SALT is paid for by Garanti, a private Turkish bank. This is part of a trend.

In September, Yapı Kredi, another Turkish bank, opened its culture centre. On its roof, a classic sculpture of a naked woman embracing life with open arms, looks toward the bustling Istiklal Avenue. Among those who see the sculpture, some climb the stairs to the top floor, and take a picture for their Instagram; others enter the library. Yapı Kredi Library has opened to the public this month, after years of renovation. Its collection consists of some 80,000 volumes and hundreds of ancient manuscripts.

Says Mine Haydaroğlu, who runs the library: “Outside, the streets are crowded; Istanbul became an eternal construction site. Readers find their peace here. Our visitors consist mostly of millennials and elderly people. The library has recently been renovated, and entering it lifts up the spirit of many.”

Just around the corner, Istanbul Research Institute, a library specializing on the city, houses 40,000 books. Those are spread among three floors organized to reflect three layers of Istanbul: Byzantine, Ottoman, and Republican. The 19th-century building, by Italian architect Guglielmo Semprini, has wooden-floors and a large collection of city monographs.

Such institutions connect Turks to the outside world. Turkish artist Halil Altındere remembers reading Artforum, the contemporary art magazine, in the library of Osmanlı Bankası, during the 1990s. Born in Mardin, an eastern Turkish city, Altındere came to Istanbul for college. He says he owes much to libraries which, in his small corner of the world, opened his eyes to the international art scene. In 2015, Altındere’s works were exhibited at MoMA; this October, his works are shown at apexart, a Lower Manhattan gallery. When I saw him inside the library the other day, he seemed comfortable. “I come here to be able to breathe,” he says.

Atatürk Library, named after the republic’s secularist founder, attracts the biggest crowds. Housing 350,000 volumes, Atatürk is notoriously difficult to get into. The effort pays off: it is open around the clock, and the main reading room offers a commanding view of the Bosphorus. The Turkish republic and Atatürk Library are the same age; long queues appear every morning around the library.

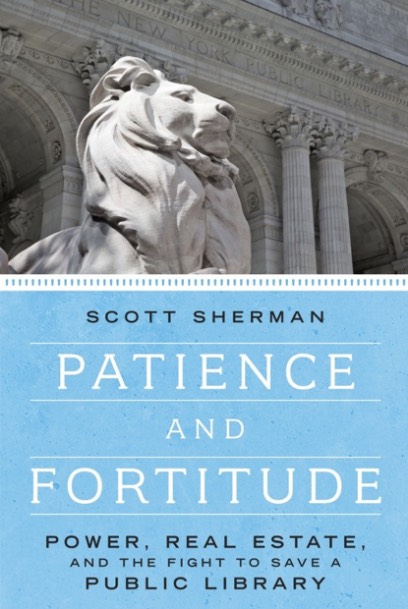

During a recent visit, I read Scott Sherman’s book, “Patience and Fortitude”, which, as it happens, concerns libraries. In 2012, Sherman, a contributing writer for The Nation magazine, covered the debate around a $300 million renovation plan for the New York Public Library.

That scheme included the selling of the library’s Mid-Manhattan branch and sending three million books to a storage facility. Many were irritated by how a Wall Street logic threatened the iconic library; others considered stocking physical books in the main library, in the age of Google Books, passé. The debate divided New York intellectuals. Publications, including The New York Times, criticized the design of the new building. In May of 2014, NYPL abandoned the plan; instead, it renovated its Mid-Manhattan branch. In April this year, Sherman visited the NYPL branches, and he found reasons for “both optimism and concern about the overall direction of the NYPL.” He visited neighborhood libraries in Washington Heights and on the Lower East Side; seeing new elevators, packed reading halls, comfortable seating areas, and good collections of books, cheered him. This month, Sherman’s book, chronicling that story, came out in paperback.

Nowadays, Sherman lives in Istanbul. In an e-mail exchange, he expressed his surprise at the difference between Istanbul libraries and the NYPL. That NYC has libraries funded by tax dollars, but Istanbul’s best libraries owe their existence to banks, surprised him.

Indeed, it takes time to see banks as saviors of culture, rather than its adversaries. But this is the case in Istanbul today. Their private libraries have introduced innovations in ways that avoided offending scholars of old-fashioned reading habits. Over the summer, SALT introduced a VR interface that allowed users to search its archives. The interface was designed in collaboration with Google’s Artists and Machine Intelligence program. The library, whose design won an award from the American Institute of Architects, hosts contemporary art installations. In March, SALT opened a new floor for specialists. It houses an extra 10,000 books. Not everyone was happy that it was named after the bank’s CEO, but many bookworms let that go.

Yapı Kredi, the bank, puts out Turkish translations of books by Ben Lerner, Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro; pays its translators well; it is, also, the publisher of Orhan Pamuk. Some years ago, Yapı Kredi used ATM machines to promote the Nobel Laureate’s new book.

In “Timon of Athens,” Shakespeare described gold, this yellow slave, making “black white, foul fair, / Wrong right, base noble, old young, coward valiant.” In Turkey, it enables a culture of reading; many, including my Marxist friends, appear grateful. This will seem strange to some, but such is the state of culture in Turkey today.