Last year, the Mexican poet Mijail Lamas organized a reading for my third collection of poetry, A Sleepless Man Sits Up in Bed (Eyewear). The event took place in the Bhutanese-style library at the University of Texas in El Paso, where I had completed a bilingual MFA in 1997. After the reading, I found myself in Mijail’s small apartment, surrounded by piles of books. I had been pestering him about obscure poets from the northern desert or borderlands of Mexico. Mijail pulled a thick tome from the top of a book tower. With the air of someone who prefers to stay silent until the moment is right, he opened Poesía reunida e inédita, a collection by Abigael Bohórquez (1936-1995), who, despite the many years he had spent in the nation’s capital, was decidedly a poet from the north. He was Sonoran in tone, his voice resonated with the languid strains of marginalization. He was also openly gay. Mijail intoned the music of Bohórquez with a dark bottle of Victoria beer in his left hand, and his right waving back and forth like a conductor’s sans baton.

The poem Mijail shared was written late in Bohórquez’s career. It appeared in his brutal and beautiful Poesida (1996), whose title alludes to AIDS in Spanish (Sida). The collection addresses the virus’s earliest victims, summoning them from the smoke-webbed region where they dwell. The speaker and the departed sadly recall loving bodies and nights of eros. The collection’s first poem addresses the departed with “vosotros,” the now strictly Iberian pronoun. This strikes a purely poetic register, calling to mind the Siglo de Oro, but also, unlike “ustedes,” suggests a deeper familiarity. You are dead, he acknowledges — but are you truly dead? The poem closes with an allusion to Vallejo: “DEAD ALWAYS AS A RESULT OF LIVING / said Vallejo / the CAESAR.”

Mijail also read a poem from Navegación en yoremito (Églogas y canciones del otro amor), which appeared in 1993. This collection in praise of masculine “adhesiveness,” as the Bard of Calamus might say, deftly mixes the slang of northern Mexico with the literary tropes and lexicon of Spanish Medieval poetry. Imagine Allen Ginsberg’s “Love Poem on a Theme by Whitman” larded with such Chaucerian vocabulary as “whilom,” “yclept,” “lemman,” and “haunch-bon.” One title reads “HERE IT IS REVEALED HOW ACCORDING TO NATURE SOME MEN SEEK THE AMOROUS COMPANY OF OTHER MEN.” The reader of classical Spanish would smile upon deciphering the following impasto of anachronistic Castilian, and the way the word “pitanza” (“daily ration”) echoes the Mexican slang for penis, “pito,” while “allegueme” (“gathered me”) alludes to a “lleguecito,” or a quick screw: “De amor echele un oxo, fabel’e y allegueme; / non cabules — me dixo —, non faguete fornicio; / darete lecho, dixe, ganarás tu pitanza.”

Mijail and I discussed Bohórquez’s biography and his growing popularity among Mexican poets. Born in a small desert town called Caborca, Bohórquez moved with his mother to the border town of San Luis Río Colorado in the state of Sonora in order to study Commercial Design. Dissatisfied with life in that San Luis — which now holds an annual literature festival named in his honor — the poet moved to Mexico City with the aim of studying film. There he met other writers, including the openly gay poet Carlos Pellicer, whose frank verse left an indelible impression on the younger man. Apart from short stretches back in Sonora, he spent almost 30 years of his life in Mexico City, although he was never entirely accepted by any of the capital’s infamous literary mafias. He eventually grew frustrated with the lack of recognition, and some of his best poetry was written after moving from Mexico City to its more distant suburbs. It was while living in Villa de Chalco that Bohórquez composed his masterful collection Desierto mayor (1980), which was awarded the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize. A decade later, Bohórquez returned to the northern desert. Slowly but surely, his reputation grew, and he began to receive belated recognition.

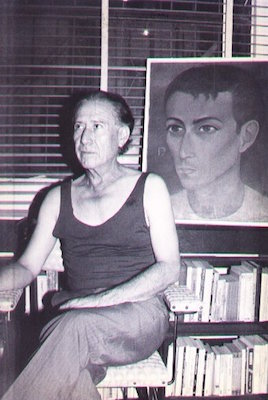

The months following my reading in El Paso were busy. Although I pledged to read more of Bohórquez’s work, it wasn’t until I traveled to Tijuana for the FeLino Festival of Literature that I fortuitously found myself staring at photos of Bohórquez while listening to a recording of him reading his verse. Entering the CECUT — Tijuana’s cultural center — I ran into my dear friend, Roberto Castillo Udiarte, a poet hailed as the “Godfather” of Tijuana’s counterculture. He smiled, stroked his white beard, and asked me to join him for a Marlboro Red by the water fountain. As he smoked he showed me a chapbook of Bohórquez’s poetry, which featured recently discovered photos of the poet proudly posing for a photographer in an art gallery. One photo hooked my gaze: The thin Bohórquez, wearing glasses, looks impossibly young for someone in his late 60s. He dons a rakishly tilted beret and stares defiantly at the camera. He is like someone in a tavern painted by Caravaggio, cut by a slant of light in a shock of chiaroscuro.

Castillo Udiarte explained that the chapbook, titled Abigael, was published by the CECUT and Pinosalados Ediciones at his insistence. Castillo Udiarte’s brief introduction to the volume is peppered with anecdotes, and recounts a reading by Bohórquez that he describes as one of the most memorable he has ever attended. Following Bohórquez’s performance at the podium, a poetaster intoned some short, incomprehensible poems. After he finished inflicting this punishment on the audience, Bohórquez asked: “Were those haiku or hotcakes?” Later, during the closing dinner for the festival, a drunken poet approached Bohórquez and exclaimed “Abigael, I’m gonna show you how to really read poetry!” and commenced reading one of his versicles, book in hand. Everyone remained silent; but then Bohórquez approached the proud vates, who was still stammering, and planted a long, deep kiss on his unsuspecting lips. The challenger dropped his book and stood paralyzed.

The CECUT organized a showing of a film about Bohórquez. Family members pieced together his life through memories and photographs, and the film also included him reading from Desierto Mayor. In a particularly stunning passage, Bohórquez offers a litany of northern Mexican Spanish that feuled his imagination as a boy. He addresses a family member, Adela, and then says he hears her and her idiom, heavy with ch’s: “chicharra, bichicori, chora, calichi, péchita, mochomo, / cholla, cachora, chorea, chilicote, / chapo, sopichi, cochupeta, bichi, / apupuchi, chiriqui, cuitlacochi.” The catalogue concludes with an apostrophe: “Oh, Thou, Poetry, deepest hollow, living flesh / now you are with me.”

Abigael includes some of Bohórquez’s most popular poems. Bohórquez wrote a poem titled “Llanto por la muerte de un perro” (“Lament for a Dead Dog”), possibly alluding to his beloved Garcia Lorca’s famous llanto on the death of the bullfighter Mejía Sánchez. This threnody is a fitting introduction to Bohórquez’s style. He establishes a correlative between the dead dog and the real dogs of society — the vicious, rabid ones who control capital, dole out wages and medicine, and rig elections. One can’t help but recall the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío’s “Los Motivos del Lobo” (“The Wolf’s Motives”), in which the wolf addresses Saint Francis: “Y me sentí lobo malo de repente / mas siempre mejor que esa mala gente” (“And suddenly I felt like an evil wolf / but not as evil as those evil people).” Bohórquez’s poem starts when he received a letter from his mother. In it she writes that someone has killed his dog: “We couldn’t figure out the source of his bleeding / he reached us gushing with anguish / wobbling / dragging himself, howling / as if from his shredded landscape / he wished to bid us adieu.”

Then the speaker responds: “My dog though a dog didn’t bite. / My dog didn’t covet nor bite. / Didn’t deceive nor bite. / Unlike those who aren’t dogs but dismember others / butcher others / and bite / from the Judge’s bench / in factories / in mills / biting the worker / the clerk / the mechanic / and the tailor.” He lovingly evokes a dog that was a mutt — as slender and simple as a spear of wheat — whom he had received as a gift when he was a boy. It had been small enough to fit inside a shoebox, but it became a radiant creature, who won’t be forgotten: “My dog was a mutt, / but he left his heart like a fingerprint; / he emitted neither a ring nor rattle / but his eyes were two tambourines; / he had no leash round his neck / but he had a sunflower for a tail / and peace for his long ears / two tongues / of diamonds.”

Pinosalados Ediciones in Mexicali may still have some copies of Abigael in their stock. It’s a keeper, as is the collected poems published by the cultural institute of the state of Sonora. Bohórquez himself is a radiant creature, diamond-tongued, whom we must shelter and hold dear.