Dear Papsters,

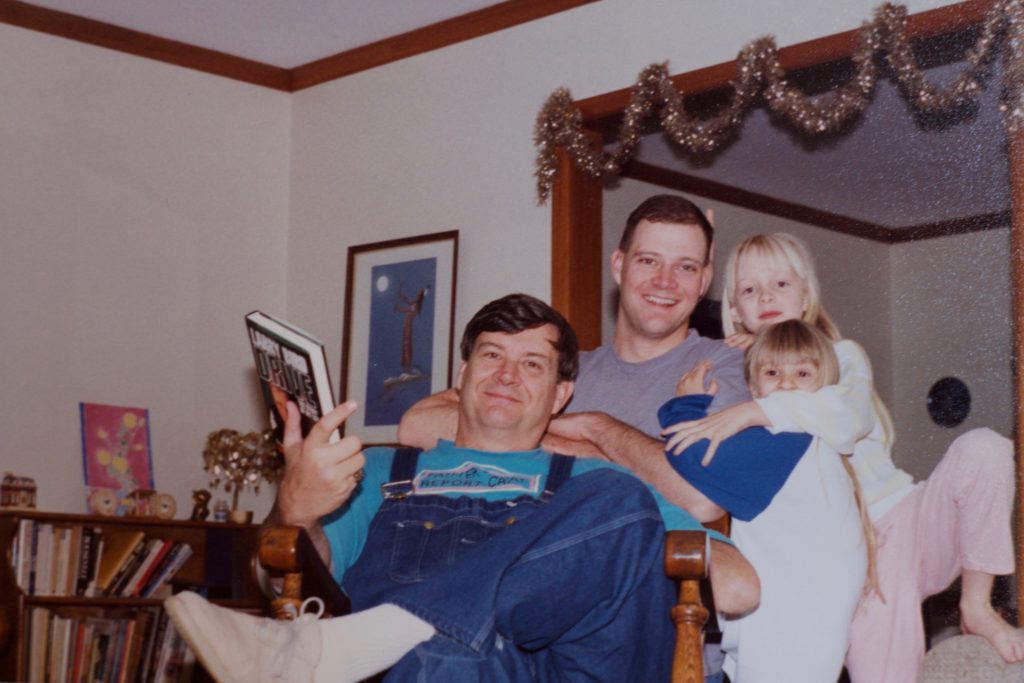

I know you’ve never been much of a reader, but you’re the reason I became one, as well as a writer and a translator of literature from Argentina, Poland and Ukraine.

I know I never would have learned any foreign language without you. I would never have had any inkling of the world, to make me want to.

You’re the one who first placed my tiny hands on the rising, falling surface of a globe. You taught college geography for 56 years — 56, your whole phone number growing up in the 1940s in Bluff City, KS. Your world was so small when you were a kid, but you found it vast. On the banks of Bluff Creek, in the cottonwood trees, in the wheat fields, in the humble houses that made up the town, you encountered trove after trove of fascinations and delights.

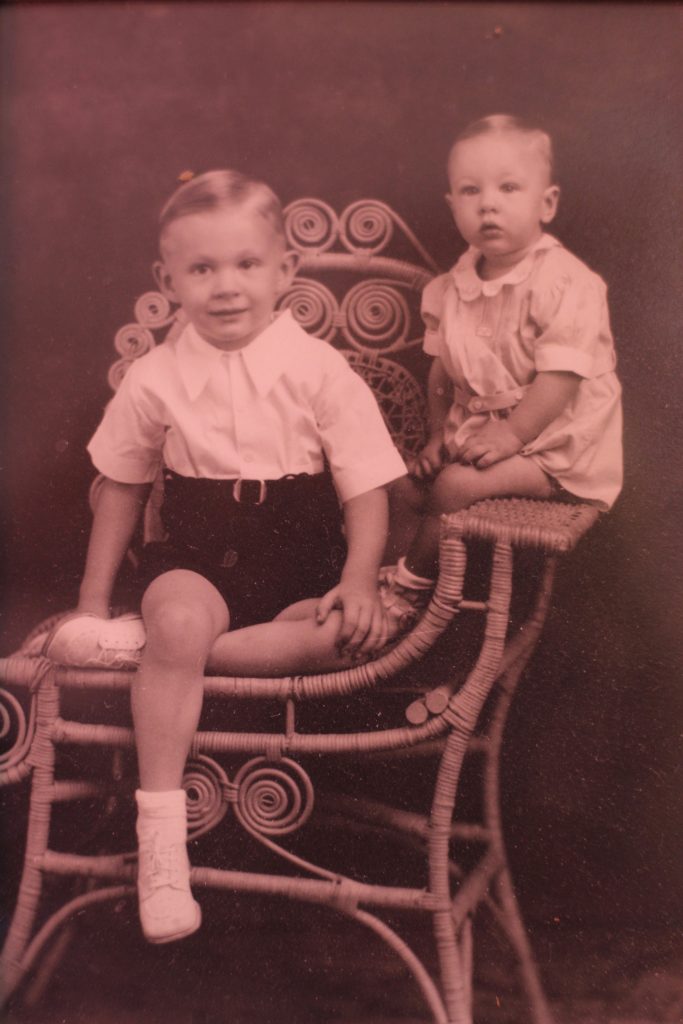

You took your little brother Richie on the same kinds of local expeditions you would later take your students on, and then Anne Marie and me. Thanks to you, we were always exploring.

I remember the wild strawberries we would go out to collect every May Day, then deposit on our front porch in blue-green baskets. We would ring the bell and hide, the three of us, so that when Mom opened the door she’d find only that anonymous bounty. At the time, Annie and I were sure we were getting away with some great crime. Now I know this was an age-old American tradition, almost completely extinct.

I remember all kinds of green and brown spots we found to play in peace on near where we were born, in Stillwater, OK. I remember bright blue swimming pools — special occasions — that you would enter first, to turn and tell us: “Come on in, the water’s fine.” You’d say it as a joke, in an exaggerated Southern accent — but it always worked: we always went in, and the water was in fact always fine — ideal for our gravity-defying handstands, our shriek-inducing tag.

Whenever we’d drive anywhere, you’d always want to try some scenic route you’d just discovered in your big, crumpled atlas. All three of us would complain. I know now you could not have been more right: what is the point of the extra three minutes provided by the highway, when it makes the whole journey bland?

I remember that at the end of my first year of school in the big city where we moved, Tulsa, my teacher, Mrs. Pancake, told you and Mom I was a good girl but that she was concerned my ability to read and write was a little bit behind the other kids. That summer, you somehow finagled a job opportunity in Prince Edward Island, Canada, and I got to go on the first of the many great adventures I would determine to spend the rest of my life pursuing.

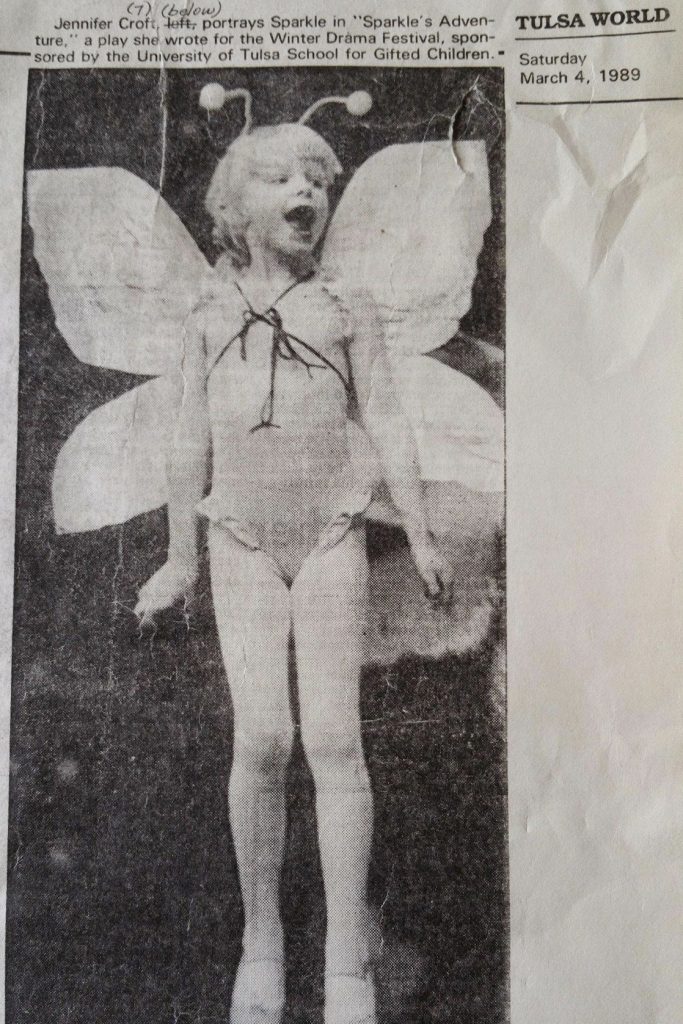

I remember flashes from that trip. I remember a great waterfall. I remember looking for amethysts and agates. I remember selecting a big, bright butterfly brooch from a glass case — my first souvenir. I remember getting home and looking at that pin and suddenly having no choice but to write a tale of travel and adventure about that butterfly, whom I named Sparkle. In a flash, I went from being gripped by vertigo whenever confronted with a blank page to soaring with my trusty pencil over notebook after notebook, defying their light blue lines. At the end of the next school year, I made Sparkle’s wild, mysterious trajectories into the class play we performed on stage for all the children’s families, and I starred as Sparkle. But I would not be that joyful and outgoing again until thirty years later — until now.

The world up until that production was a kind of idyll; like any paradise, it was destined to be lost. Soon my spelling bee words went from chrysanthemum and onomatopoeia to pilocytic astrocytoma as Annie started having seizures and was subjected to CT scans and blood tests until she was finally diagnosed, the brain tumor and its treatment wreaking havoc on her life, but also on ours, for all the years to come. She was only six years old when she had her first brain surgery; I was nine.

Soon I would slide into severe depression, out of sympathy for my sister and because I felt so alone. Soon I would wind up in the hospital, too, after trying to commit suicide. And almost immediately upon my release, you would go in for a routine checkup, only to discover you had developed chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or CLL.

Our lives, once unbounded, now took place within the confines of the hospital or on the way there or back. But did you ever let that radical overhaul of everything reframe your vision of the world?

Twenty years after your diagnosis, your doctors all call you a medical marvel. You’ve had terrible shingles, terrible foot and mouth disease, too many bouts of pneumonia to count. CLL has ruined your immune system. Chemotherapy has eroded your body’s other resources. You’ve had four bone marrow biopsies. You’ve had bladder surgery and an emergency tracheotomy. Two summers ago, you broke your hip.

But you haven’t changed, except perhaps to get a little more compassionate, softened by seeing so many like you who suffer from cancer get sicker and pass away. But you have always been consistent in sticking to certain precepts, no matter how stressful things get. You never really told us what to do when we were growing up, allowing us to draw our own conclusions. But based on how I’ve seen you behave, here’s a list of guidelines I will always strive to follow:

- Will positivity

Just about every time I’ve ever called you, you have told me I called at the perfect time. I know perfectly well that can’t be true, that half the time you were probably right in the middle of something, or about to go somewhere, or on the other line. But you have always made me feel more welcome than anybody else in the world, and I hope to be able to convey that feeling — maybe the best feeling there is — to my own kids someday, too.

- Keep perspective

Wherever I’ve lived, you’ve always asked me if I could see the stars. It’s a simple question, but it acts as a reminder to pause and look up — away from the minor quotidian stresses, all to be forgotten by the following week. It helps me to be mindful that the universe can be beautiful and is always much bigger than my own fixating brain.

- “No” just means “move on”

There is always something else to try if an opportunity falls through. As a literary freelancer, my rejections always outnumber my acceptances, and it’s hard not to get discouraged sometimes. But this is an idea that would benefit anyone, in any field. Don’t take things personally; just try again somewhere else or do things differently — but don’t give up.

- Practice what you love. It doesn’t need to make perfect

You used to spend ten hours a day shooting baskets out in the dirt by your house growing up. 65 years later, you would tell me that what you wanted was not to always be able to do the same thing, but rather to be able to make a game-winning shot. You could have become a professional athlete, but you chose to pursue a doctorate in geography instead. In the end, that was your game-winning shot, the thing you loved the most. It also allowed you to introduce thousands of students to the world.

- Education is important

You discovered geography in fourth grade, when it was first a subject in your school, and not long after, your mom surprised you with a World Book and a subscription to National Geographic. You did these things for me. When in eighth grade I took an interest in the Russian language, you tracked down a textbook and even a teacher, a former student of yours, from what was then called Dnepropetrovsk. You always encouraged — strongly — Mom and Anne Marie and me to get a great education. I know I only have a PhD because of you.

- Everybody comes from somewhere

This means everyone has an interesting story and is interesting. If you take enough of an interest, you’re bound to learn from anyone as well as figure out the many things you have in common, no matter who it is. People’s backgrounds, even their very recent histories, may help you understand their behavior now, which in turn may enable you to react to them more kindly.

- Cultivate kindness

One time you came to visit me in Krakow, one of a handful of times you made it over to Europe, while I was on my Fulbright year. One rainy afternoon we thought we’d see a movie, but the only option seemed to be a film in French with Polish subtitles. Not only did you agree to give it a try, despite speaking neither of those languages, but also every time I looked over at you in the theater, your expression was delighted and rapt.

- Few things are more exciting and uplifting than travel

Even talk of travel has always thrilled us over early-morning coffee. Travel is how you get access to more people, more ideas, more landscapes that generate or bring to the fore all kinds of unknown or underfelt feelings. The only way to know something is to be there.

- Ask for help

This may be the most powerful secret weapon in your armory. You are so self-assured you have never been hampered by pride. You are never embarrassed to ask questions. This, the simplest type of defiance, has gotten you and your family out of so many scrapes, and it has undoubtedly saved your life when doctors overlooked things only to see them in response to your thoughtfully voiced bewilderment.

I can’t imagine going from gifted athlete to person who needs help getting around, doing just about anything, but you don’t let it faze you. You seem to simply know that help and cooperation are fundamental values, and that no one can do anything without other people, anyway.

- The goal of life is to enjoy life

Of all these precepts, this may be the hardest one for me to master. I get more stressed than you seem to, worried about money and time. But whenever you make a dad joke, and everyone groans, you warn me that it runs in the family. Whenever I make a mistake, you say I take after you. That’s true. I hope I take after you, and I look forward to taking risks, trying and failing and trying again, and I know that my ability to not give up is thanks to you. I also know I’ll eventually make the big shot of feeling happy and comfortable in my life, like you do.

You’ve never been much of a reader, preferring globes to books, but it makes me happier than words can say to think that you will be able to read this letter, in spite of everything you’ve been through over the past twenty years.

Since my debut as Sparkle the butterfly, I have written and translated so many stories, poems, books — but I also know that every word I ever write will be in that same spirit, that same awe in the face of the world’s glittering, beckoning multiplicity, the way it whispers, beaming, “Come on in, the water’s fine.”

Love,

jlc