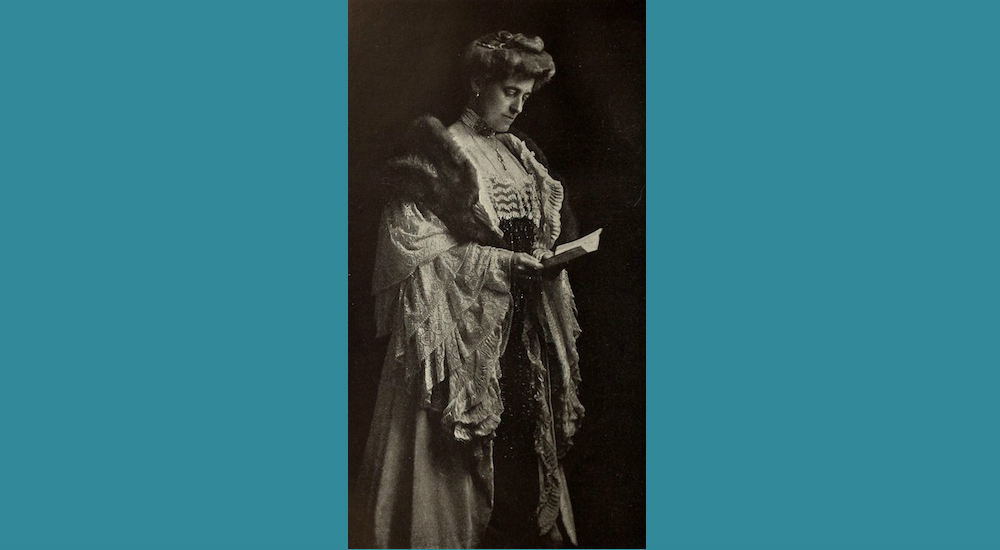

Initially serialized in four parts in the magazine Pictorial Review, The Age of Innocence is Edith Wharton’s 12th novel, and she wrote it when she was in her 50s, having already established a literary reputation. Almost universally acclaimed, The Age of Innocence won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921, making Wharton the first woman to win the prize. The novel is still widely recognized, and it remains one of her most beloved works. Her first published book was not a novel but an influential treatise and manual for house decoration, The Decoration of Houses, written in collaboration with the architect Ogden Conman Jr., and published in 1897, forecasting her comprehensive skills at detailing place and setting in her later fictions.

Old New York society’s deep-seated, insular, rigid clans of first families, typically of Dutch and English ancestry and dating back to Revolutionary America, provide the fertile soil for most of Edith Wharton’s oeuvre. The Age of Innocence has a more subtle vision than its predecessors, The House of Mirth, and the acerbic, undervalued The Custom of the Country, though Age of Innocence retains her signature irony, as it is “the innocence that seals the mind against imagination and the heart against experience.” Wharton, who grew up entrenched in this stultifying environment, wrote The Age of Innocence in the wake of World War I, at a wistful removal from the novel’s 1870s setting, and from the distance of France, which she’d long since made her home. The novel moves beyond her customary anthropological-like satire, and also becoming a surprising paean — infused with longing and melancholy — for what she considered the disappearing, jeopardized values and culture of this selfsame society. “In my youth,” she wrote in her memoir A Backward Glance, “the Americans of the original States, who in moments of crisis still shaped the national point of view, were the heirs of an old tradition of European culture, which the country has now totally rejected […] The compact world of my youth has receded into a past from which it can only be dug up in bits by the assiduous relic-hunters; and its smallest fragments begin to be worth collecting and putting together before the last of those who know the live structure are swept away with it.”

Wharton as “relic-hunter” clashes the positive values of her birth family’s social group with their narrow, unimaginative, cutthroat disregard toward anyone different, or anyone who threatens traditions. New York City, Newport, Rhode Island (where Wharton’s family had a summer house), and, in its final pages, Wharton’s adopted home of Paris, serve as her charged, specific landscape. Now a Starbucks, Wharton’s birthplace and childhood home, 14 West 23rd Street, is also the birthplace of her imagined Gilded Age New York.

Within the Mingotts, the Mansons, the Van der Luydens — who prevail at being rich and retaining their wealth, using social conformity and, most importantly, making sure to keep these codes enforced — Wharton plants Newland Archer, who belongs deeply to family and tradition, yet who also finds himself in growing conflict with these forces, craving more from life, and wanting to rebel. This conflict is incarnate in Archer’s loveless fidelity to his fiancée (and later, wife) May Welland, a physically, intellectually, and emotionally perfect creation of society, with no agency beyond clan preservation; and by Archer’s passion and love for Ellen Olenska, also a clan member and May’s exotic cousin, who temporarily freed herself via Europe, only to return to New York, chastened, hopeful, seeking reprieve and safety within its confines, having separated from her philandering, worldly, morally bankrupt Polish count husband. Uniquely and excitingly herself, Olenska is not afraid to flout conventions, and though she reciprocates Archer’s devotion, it’s complicated. Archer tells her, after not seeing her for some time, in a steamy and chaste carriage ride: “Each time you happen to me all over again.” But theirs is a love story with a paradoxical twist: in Wharton’s vision, Archer and Olenska can only prevail by sacrificial imperative. In order to keep the kiln burning, they must abandon each other for the greater good; otherwise their love will be sullied and, no doubt, degenerate into the common.

Wharton knew a great deal about unrequited love, having had a lifelong, unreciprocated love for her close friend, the lawyer Walter Berry, who, naturally, was unworthy of such devotion. She remained in an awful marriage to Edward “Teddy” Wharton, or “cerebrally compromised Teddy,” as Henry James privately christened him. Mentally ill and an alcoholic, Teddy never worked, living off their inheritances and her income. After he embezzled Wharton’s money to house one of his mistresses, she finally divorced him.

People, as Wharton so beautifully reveals in The Age of Innocence, are creatures of their environments, their physical surroundings and psychological makeups inescapably connected. As Wharton noted in her Yale University honorary talk (again, like the Pulitzer, the first woman to receive the honor): “Character and scenic detail are in fact one to the novelist who has fully assimilated his material,” and “the impression produced by a landscape, a street or a house should always, to the novelist, be an event in the history of the soul.”

In her short story “The Fullness of Life,” Wharton wrote, “I have sometimes thought that a woman’s nature is like a great house full of rooms.” Ellen Olenska’s drawing room reminds me of Wharton, Olenska’s “skillful use of a few properties,” having transformed it “into something intimate, ‘foreign,’ subtly suggestive of old romantic scenes and sentiments.”