In the opening chapter of Tommy Orange’s debut novel There There, Tony Loneman reflects on the first time he recognized his face, which bears the mark of fetal alcohol syndrome and singles him out for mockery from his classmates and fear from strangers:

Your face in the mirror reflected back at you, most people don’t even know what it looks like anymore. That thing on the front of your head, you’ll never see it, like you’ll never see your own eyeball with your own eyeball, like you’ll never smell what you smell like, but me, I know what my face looks like. I know what it means.

Tony sees his own face reflected in the darkened turned-off television screen, a moment of startling clarity at age six: he and his face are different because of pain and trauma inherited from his Native American relatives, which he had no control over. To varying degrees, it’s a question that runs through the minds of each of Orange’s characters as their histories and thoughts ricochet off one another and they draw inexorably closer to the novel’s chilling finale, a fatal powwow in Oakland, California. Sometimes characters speak to us directly, like Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, who remembers moving as a child to the native-occupied Alcatraz with her mother and sister. Sometimes they speak in a removed second person as if narrating their own actions, like Thomas Frank, who finds reprieve from his alcoholism in the rhythmic powwow drumming. Sometimes the perspective shifts from first to a more distant third for the same character in different sections. The result is expansive, as if we were standing between two mirrors and seeing a different self reflected back in each one.

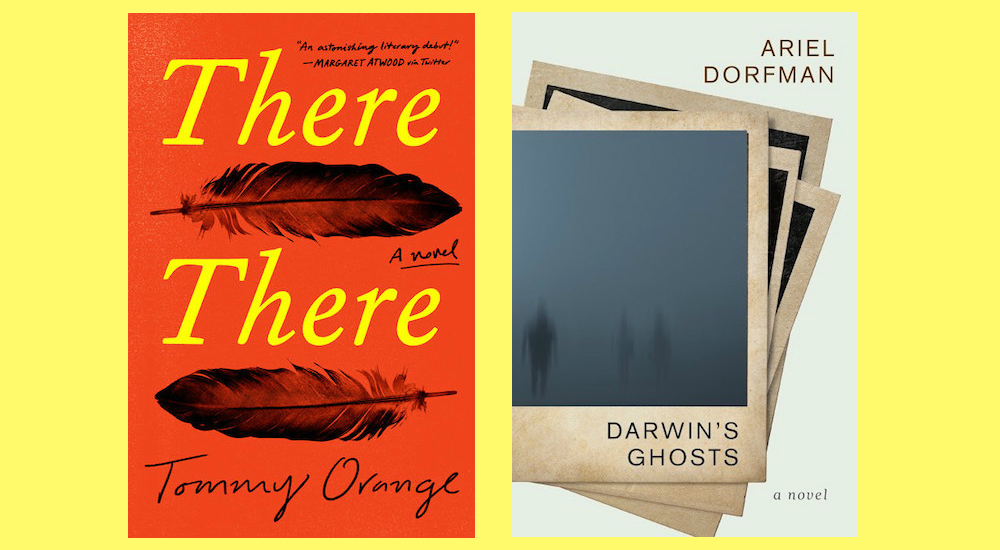

To look in the mirror and like what you see, or at least understand it, is taken for granted by many, but to those for whom it isn’t automatic, it’s chaos. Two books published this year — Orange’s debut novel, and the Chilean American novelist Ariel Dorfman’s Darwin’s Ghosts — deal with this dilemma in very different ways, reaching different formal conclusions as to how the novel might address the question of recognition and representation.

¤

Dorfman’s narrator, Fitzroy Foster, is the descendent of two 19th-century figures tied to the history of exploitation of indigenous peoples in the Americas. Told by a Fitzroy looking back on the events of his life, the story opens on the day of his 14th birthday, which is when his father captures on a polaroid a face that is not Fitzroy’s, but the visage of a “primitive alien.” The man has dark hair, dark skin, and dark eyes, all of which draw horror and chagrin equal to Tony Loneman’s, though for different reasons. When it’s discovered that his visitor shows up in every subsequent photograph of Fitzroy, no matter the model of camera or angle of lighting, it diminishes his life, tears apart his family, and sets the novel on a course of adventure, intrigue, and searching of historical archives.

Darwin’s Ghosts follows Fitzroy, his family, and his girlfriend Camilla “Cam” Wood as they attempt to uncover the identity of his mysterious visitor. Eventually they learn that he was a member of the Kaweshkar tribe of Patagonia. He was kidnapped and taken to Europe as part of the trafficking in indigenous peoples for the hugely popular human zoos of the 19th century. He later died of syphilis. According to an author’s note, these details of Henri’s life (the name he was given by his captors) are based in fact, but the reasons behind his possession of Fitzroy’s photographic countenance are never fully illuminated beyond a vague imagining of desired revenge, a life unfulfilled, and an opaque message from beyond the veil. The obsessive hunt for Henri’s fate is the main driving force behind the narrative. It pulls the characters from France to Zurich to the Falklands to Patagonia and Guantanamo Bay, all the while pursued by high-tech wizards with degrees from MIT who want to run experiments on Fitzroy and uncover the genetics of “inherited visual memory.” If it sounds convoluted, it is; the spectacular occurrence of Henri’s appearance is simultaneously not enough for this narrative, and too much for it to handle, and so instead it veers off in the direction of a James Bond thriller.

The thing about thrillers is that they are more concerned with what the main characters are looking for, as opposed to how they are looking at it in the first place. When you wander around your house looking for your keys, you can’t take notice of other things unfolding around you if you ever want to leave for work; you have to enact tunnel vision. Thriller novels are exciting at times, and Darwin’s Ghosts succeeds in eliciting a feeling of suspense, albeit one that is plagued by an amnesia subplot and unbelievable female characters who drop sexual innuendos like old men and live to serve their male family members. But ultimately, Henri becomes a plot device, a puzzle that Cam and Fitzroy have to figure out before they can go on to live their lives in peace. It’s one that, at times, introduces moral quandaries, but they’re never insurmountable — the answer is always on the next archival page. By focusing on the hunt for clues, Dorfman narrows the plot in such a way that the reader is no longer an active participant in looking, they are not encouraged to interrogate the assumptions they bring to a scene or a description. The author points to something, and the reader looks.

Early on, Dorfman does succeed in capturing the feeling of alienation from one’s life and face, and this breathes some life into the central question of the novel: how do the “innocent ones” make up for the crimes of our ancestors? But while the question rings clear, the answer is muddied, if it’s there at all. The book ends with a neat deus-ex-machina, hinting that, for Fitzroy, the desire for resolution and a normal life was stronger than the impulse to fully explore atonement.

¤

In one scene from There There, a drone comes careening into the empty stadium that will later be the site of the powwow. It zings down to ground level, where Bill Davis, a janitor, swats at it with his trash-grabber, chasing after it and almost capturing it from the sky before it zooms back up and away. We are that drone with Orange as pilot. Piloting us as he does, he makes us zoom in and out, sometimes dizzyingly, to accompany his characters as they try to figure out how to live as the ancestors of the victims of those same genocides that Fitzroy’s ancestors benefitted from. It is not a question of which direction is more worthy to be told; both are important. But how we read these stories is crucial. In hunting for clues on an adventure story, we lose sight of what’s outside the frame, so that we’re incapable of pivoting to different perspectives. It is top-down, managed, while Orange’s vision is more complicated. How we look at the crimes from our past, whether perpetrated by us or on us, matters.

Many will say that Orange, being a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, is simply more capable of telling this story, and while that may be true, it is also reductive. This type of thinking misses the fact that it’s the formal choices, the narrative structure that Orange is using that brings to life the many different ways to be native. This invites the reader to not just see native characters, but also, in a subtle but crucial rhetorical shift, to see the world with them.

In an authorial intermission which comes in the middle of the novel, Orange writes the following:

If you were fortunate enough to be born into a family whose ancestors directly benefited from genocide and/or slavery, maybe you think the more you don’t know, the more innocent you can stay, which is a good incentive to not find out, to not look too deep, to walk carefully around the sleeping tiger.

Dorfman is looking, but it turns out that to really reexamine this history, we need more than that. We need readers and writers like Orange, who engage with both the trappings of narrative and how a story is told.