I make the drive from Los Angeles to San Francisco at least once a year. The big city of my childhood draws me back for all manner of reasons, from family reunions to baseball games. Usually I speed as fast as I can up the 5 to make it in time for a dinner or a coffee date with an old friend. I planned my last trip a little differently and decided to drive up along the coast, my copy of Big Sur in hand.

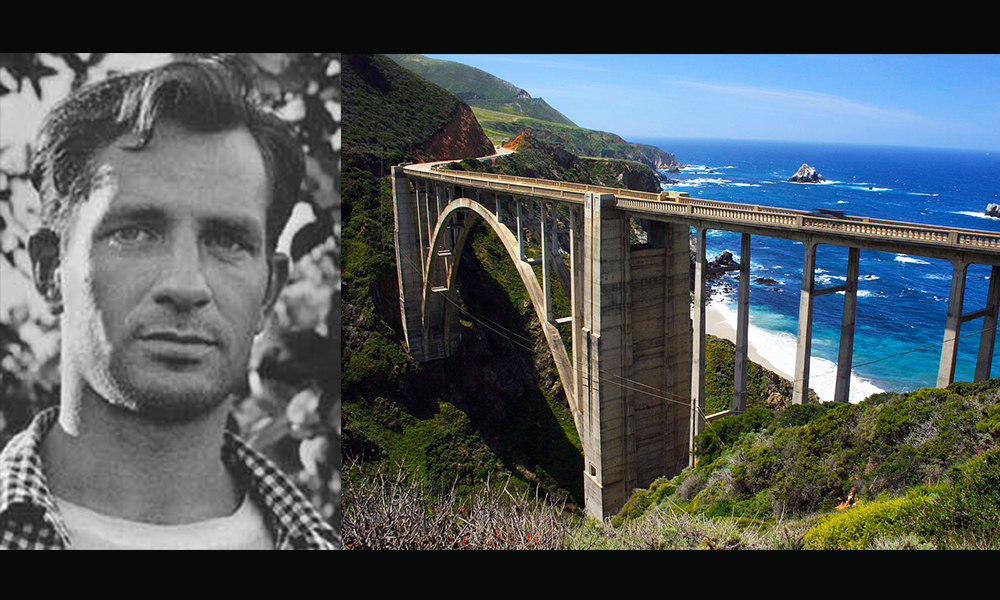

If I had been to Big Sur before, it would have been in my childhood, and I don’t recall it. That being the case, I wanted a guide, and Jack Kerouac seemed like an excellent one. I knew that the Big Sur of the 2010s would be different than Kerouac’s of the 1950s and ’60s. I drove north with the hope that remote cabins like the one Kerouac borrowed from Ferlinghetti would still exist, even if I couldn’t gain access to them.

Upon reaching Big Sur, I found Nepenthe, which Kerouac describes as “a beautiful clifftop restaurant with vast outdoor patio, with excellent food, excellent waiters and management, good drinks, chess tables, chairs and tables to just sit in the sun and look at the grand coast.” It is still the way that Kerouac wrote, and I was glad to sit outside in the sun and look out over the ocean.

With many miles of winding road still ahead of me in mind, I opted for a non-alcoholic beverage and hoped Kerouac’s ghost wouldn’t judge me too harshly. It seems very out of character to not drink alcohol while in search of Kerouac, but my practical side won out over my romantic inclinations. I opted for their seasonal shrub.

Sitting in the bright sun, I cracked open Big Sur and tried to manoeuver my way under an umbrella to avoid the reflection of sunlight from the pages. It is a perfect book to dive into to not only get a glimpse of this area in a bygone era, but also to see how one writer deals with the aftermath of his success.

Jack Duluoz is the novel’s stand-in for Kerouac, much like Sal Paradise is in On the Road. In Big Sur, the success of On the Road has gotten to Duluoz. He’s in constant motion for much of the book, trying to find a place that feels comfortable, where he doesn’t have to live up to strangers’ expectations of him after they’ve read his book.

He finds that place in Monsanto’s cabin at Big Sur. Monsanto — Laurence Ferlinghetti’s alias —provides a place for Duluoz to get away to write and drink himself as drunk as he wants in the canyons that stretch back into California’s interior from the coast. Bixby Creek, where the cabin sits, is home to one of the most famous sites in Big Sur, the Bixby Canyon Bridge. Owing to its beauty and enduring popularity, I was convinced that there was no way to sneak back into the canyon. Even had there been, I was not confident I would find Ferlinghetti’s cabin.

Sitting in the sun at Nepenthe, I was surrounded by other visitors to the area. Some, like me, were just stopping while driving through. Those who were staying had my envy, though, as I wanted more time to explore this bit of the California coast. I will confess, it’s my first time reading Big Sur, and I am glad to be doing so in its titular location. While not all of the novel actually takes place in Big Sur, I’m pleased to see that much of it does. There are even parts that echo my own travel up to San Francisco from Big Sur.

The depiction of life in Big Sur is deeply appealing to me, as are all accounts of how people lived simply and quietly in places that have now become oversaturated with visitors. I am one of those visitors, so I cast no blame, but I am also glad for my guide to the past. Monsanto tells Duluoz, “‘This is the kind of place where a person should really be alone, you know? When you bring a big gang here it somehow desecrates it…’” “Which is just the way I feel too,” Duluoz adds.

I cannot help being part of the big gang of visitors to Big Sur, but I keep picturing the cabin where Duluoz (fictionally) and Kerouac (in reality) spent their time writing and wandering the canyon, doing small menial tasks that seemed to have turned meditative as they worked. Kerouac writes of the solitude of the cabin and its sudden change when the weather turned nice: “I was amazed to hear laughing and scratching all up and down the valley which had been mine only mine.” I wish I could see the place in his solitude.

In addition to telling me something of the history of the area, I also enjoy reading about the complications that arise from a successful writing career. Kerouac deals with the pressure of fame and what people expect from him in the aftermath of On the Road, and that too is fascinating. As a bookseller, I have often seen the enduring popularity of On the Road, which teenagers today still buy in volume. I don’t know if they imagine themselves having the same adventure, or if they want Kerouac to speak to them. I can’t judge — I’m sitting with a copy of Big Sur, expecting the same.

What struck me was the very beginning of the novel, when the reason for his trip to the isolated wilds of Big Sur is explained. He writes of the aftereffects of On the Road’s popularity: “I’ve been driven mad for three years by endless telegrams, phonecalls, requests, mail, visitors, reporters, snoopers … Teenagers jumping the six-foot fence I’d had built around my yard for privacy.” Not many people write work that affects their readers so much, and it appears as much a hassle as a blessing. To be clear: there are a lot of authors I, too, love. But even writing a letter to them often feels invasive. In the 21st century, it’s easy to follow a favorite author on Twitter or Instagram, but I feel weird tagging them, unlike the unruly legions of Kerouac fans.

The kinds of things I write — this very essay, even — don’t exactly inspire the kind of reaction Kerouac’s writing did. With that in mind, I don’t expect to learn how to deal with overwhelming success and popularity, but I still have lessons to learn from him and how he encountered the pressure of his newfound fame.

Going away to the woods is a classic American trope, although we find it in the ancient hermits of Europe and the Middle East too; but for Americans, we look back to Thoreau and Walden as an ideal for the restorative powers of escaping from society, even temporarily. And, to be honest, even Thoreau wasn’t so great at actually escaping, with his frequent visitors and the amenities they brought him from civilization. Kerouac falls into a similar mold, with his escape to Big Sur and the eventual encroachment of the city. He not only returns to San Francisco to get the perks of the big city, like bars and friends, but he then brings them back with him to Big Sur, ruining the solitude he had so enjoyed previously.

What lesson does he have for me in that narrative? I see that not only is taking time away to clear one’s thoughts and give creative work space to ferment important, but so is drawing boundaries. I can learn from Kerouac and Duluoz’s mistakes, and make wiser decisions about how and when to let others into the space I’ve carved for myself.

All of that feels a little intense for my reaction to a novel read while enjoying a drink and lunch along one of the most beautiful stretches of California coastline. Nevertheless, spending my own time in solitude here has led to some of the same mental fermentation that Kerouac’s time in Big Sur did for him, I think. I enjoy watching the couples and families and groups of friends at Nepenthe, but I am still alone with my thoughts among the crowd.

After I finish up my meal, I walk to the edge of the patio to look down on the water. In that moment, my solitude in the crowd is amplified. No one else stands along the bit of railing I’m using. It’s just me and the ghost of Jack Kerouac, both of us longing to be alone here in this beautiful place.