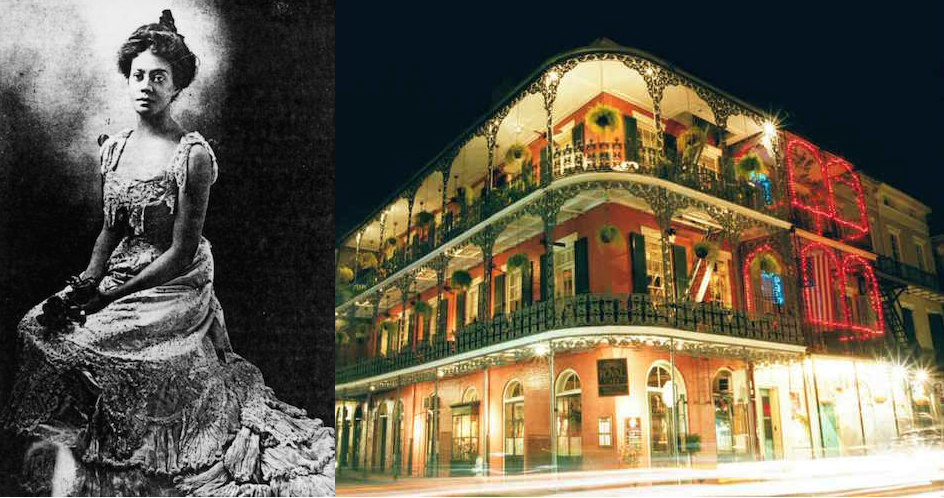

Heading to New Orleans, I knew I had to do some searching to find the right author to spend time with in the city. The most famous New Orleanian writer I know, Anne Rice, is still alive, although her work certainly lends itself to the idea of hanging out with her ghost. I wanted to spend time with someone who was different from the old white men with whom I have previously visited, and so after some research, I chose Alice Dunbar-Nelson, a fin-de-siecle African-American author originally from New Orleans. I knew she could bring a perspective I was interested in, that of a woman of color in a time that was generally less kind to both women and Black people. Dunbar-Nelson was a poet and journalist, and part of the first generation of people born free in the South after the Civil War. Her work, which largely focused on the experience of being a multi-racial woman, was not widely distributed even during her life.

In preparation for my trip, I combed the stacks at the bookstore where I work for anything by Dunbar-Nelson, to no avail. I called a number of New Orleans bookstores, and no luck there either. One highlight for me was coming across a bookseller at Beckham’s Bookshop in New Orleans who was eager to tell me a bit about Alice Dunbar-Nelson, an “interesting New Orleanian,” as he described her, and I think he was right. A Black woman writer in her era was unusual, and for her to not only make a living as a writer, but to marry and divorce a few times made her stand apart from many of her peers.

Thanks to the wonders of the digital age, I bought and downloaded a few of her works on my Kobo app (gotta keep that indie spirit alive!), and brought her with me everywhere I went in New Orleans. I wanted to sit and grab a drink with Ms. Dunbar-Nelson, so I picked up Violets and Other Tales to see if she had any recommendations. Though it turns out most of her favorite places don’t exist in the 21st century, her words led me to an intersection that is home to a famed New Orleanian bar.

In “Anarchy Alley,” she describes life on Exchange Alley in the French Quarter. “It is Bohemia, pure and simple, Bohemia in all its stages, from the beer saloon and the cheap bookstore, to the cheaper cook shop and uncertain lodging house.” Seeing the French Quarter through her 19th century perspective was far more romantic and picturesque than the glut of souvenir shops and street hawkers I saw before me, though I think it’s impossible for those elements to negate the innate charm and beauty of New Orleans.

She continues describing Exchange Alley and its attractions: “Plenty of saloons — great, gorgeous, gaudy places with pianos and swift-footed waiters, tables and cards, and men, men, men. The famous Three Brothers’ Saloon occupies a position about midway the alley…” The Three Brothers’ Saloon no longer exists, but near where it once stood is the Carousel Bar in the Hotel Monteleone, which certainly meets her other qualifiers, and is renowned for the literary greats who drank there, although it is only Ms. Dunbar-Nelson with whom I want to visit. It is in that great, gorgeous bar that I sat down to drink with her and get her perspective on a city that I longed to see in its heady 19th century glory.

A live jazz band was playing (how could there not be) and the bar was crowded with professionals enjoying happy hour after work at the start of a weekend close to Christmas. The bartender was as attentive and swift as the waiters of old, and got me a Sazerac, which seemed only appropriate in the city in which it was invented.

I found a spot to sit — no small feat in a bar packed to the gills — and settled in to listen to jazz and have a peek into the world of old New Orleans through Dunbar-Nelson’s eyes. I read two of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s short story collections, which provided me with glimpses of life in and around New Orleans and across class lines over a century ago.

There are a few stories that overlapped in the collections I read, Violets and Other Tales, and The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories. One of those is “A Carnival Jangle” which tells a tragic tale of mistaken identity during Mardi Gras. But before the tragedy hits, she vividly brings the spectacle of Mardi Gras to life:

There is a merry jangle of bells in the air, an all-pervading sense of jester’s noise, and the flaunting vividness of royal colors; the streets swarm with humanity, — humanity in all shapes, manners, forms, — laughing, pushing, jostling, crowding, a mass of men and women and children, as varied and as assorted in their several individual peculiarities as ever a crowd that gathered in one locality since the days of Babel. It is Carnival in New Orleans…

As a visitor in December, I did not get to experience the wild jumble of humanity that Mardi Gras brings, but I was content with the view she provided. During her short story, I felt a whirl of activity and sensations in her description of Mardi Gras — and a Mardi Gras from the past at that. No drunken frat boys or sorority girls yelling from the balconies, but rather the wild crowd of yesteryear. I was eager to see what else she could illuminate, and delved further into her work.

In her stories, I visited with bay and bayou dwellers, whose lives were foreign to me through both the lenses of distance and time. Knowing that Dunbar-Nelson was African-American, I read her stories trying to figure out if the characters were as well, curious for a glimpse of New Orleanian life for Black people at the turn of the century. Her stories occasionally specify that someone was Creole, presumably mixed-race with that distinction, or that they were of Spanish or French blood, but I never felt certain whether her characters looked like her or not, which is a distinction that reads differently today, when people purposefully seek out diverse representations in literature. It makes me wonder if that is a result of a push from her publisher to make her characters as accessible as possible to the widest audience by never clarifying much on race, or if that was an intentional choice of Dunbar-Nelson’s.

She writes more explicitly about issues of class, with poor people and their fates drawn out in several of her stories. In “Mr. Baptiste,” the story’s namesake is a homeless man who lives on the kindness and good graces of the people in the neighborhood he roams. They feed and house him in exchange for the fruit he obtains from the dockworkers at the port in New Orleans. His possessions are meager, but in his story I see a recurring theme of New Orleanian generosity: “And madame, who understood and knew [Mr. Baptiste’s] ways, would fry him some of the bananas, and set it before him, a tempting dish, with a bit of madame’s bread and meat and coffee thrown in for lagniappe.” Children are given extra candy as a lagniappe, or a banana to go with the coal they retrieve for their families. It is a New Orleanian precept, and throughout Dunbar-Nelson’s stories, characters give and receive lagniappe. I love this idea of giving a little extra, or lagniappe, just for the sake of it. Other characters do not receive that same bit of kindness, and are left to their destitute fates in her immensely readable stories. I visited Commander’s Palace, queen of the New Orleans culinary scene, and the first place I learned about lagniappe as a visitor many years ago. The little lagniappe to start my meal reminded me that the New Orleans of Dunbar-Nelson’s time persists.

Dunbar-Nelson not only brings scenes from New Orleans and its environs to life through her vignettes, but she also provides some astute commentary on the world through her characters and even through the introduction in which she addresses her reader. In “M’sieu Fortier’s Violin,” a friend of the young man who wishes to buy the titular violin chastises him, saying, “You are like the rest of these nineteenth-century vandals, you can see nothing picturesque that you do not wish to deface for a souvenir; you cannot even let simple happiness alone, but must needs destroy it in a vain attempt to make it your own or parade it as an advertisement.” It almost feels like an admonishment to the Instagram generation (of which I am a part), who cannot see anything lovely without wishing to pose with it or manipulate it for the sake of more likes on social media. Maybe I’m too pessimistic, but I feel as though that derision applies not only to a young man of the 19th century, but also to his successors in the here and now. Sitting at the Café Du Monde, taking a picture of my beignets before eating them, I saw that I was not alone in this pursuit and that crowds of fellow tourists couldn’t eat their sweet treat without first documenting it and showing it to the world.

She also gives some sound advice to the women who read her work. She cautions, “Why should well-salaried women marry? […] no troublesome dinners to prepare for a fault-finding husband, no fretful children to try her patience […] She has her cares, her money-troubles, her debts, and her scrimpings, it is true, but they only make her independent, instead of reducing her to a dead level of despair.” It feels revolutionary to have a woman of that era, particularly one who married several times, advise women to delay marriage if not altogether avoid it. As an unmarried woman, it felt like I was getting direct advice from an older, more experienced mentor as she extolled the virtues of singleness.

My drink finished, I set aside Dunbar-Nelson’s words and prepared to go out into the New Orleanian night, with visions of the past filling my mind. I appreciated her frank words and the characters who wandered the streets of the New Orleans with me. She is an under-appreciated writer who captures the spirit of New Orleanian life at the turn of the century, and I am so grateful for the time I spent with her and the perspective on her city she gave me. Her insights may have been from over 100 years ago, but she showed the enduring spirit of New Orleans and its people.