“How stupid those smugglers of Chinamen were at Niagara,” the narrator fires his first shot as the 1904 short story “How White Men Assist in Smuggling Chinamen Across the Border in Puget Sound Country” opens. Identified only as “the man with the sun-browned face,” our mysterious protagonist is rough and tumble, a former sailor and prospector, an ethical trash-talker dishing out digs to the stuffy East Coast and the unjust government. “West [C]oast adventurers,” he tells us, seizing on the fluidity of the frontier to circumvent more intransigent national borders, “have a code of morals entirely their own.”

The story, originally published in the Los Angeles Express — a long-running big city daily — is an exquisite caper. Fresh and penniless from the gold fields of Alaska, the tanned man joins forces with a renegade band of Irish and First Nations men to smuggle undocumented Chinese immigrants disguised in redface from Vancouver Island to Washington State. It’s the height of the virulent border controls ushered in by Chinese Exclusion. There are movements by land and sea, brushes and near-busts with the patrolling revenue agents, hiding places in domestic outposts minded by shrill old wives, and sunrises beheld from the craggy peaks of the Olympic Mountains. At the end there’s a cash payout, a sinister glimpse at a highbinder agent — the literal hatchet men of Chinatown’s Tong Wars — and a train full of Chinese immigrants receding on the horizon line as they head south to ‘Frisco. And that was just the beginning. “Since then I’ve helped run over 200 Chinamen into the United States,” the narrator volleys menacingly, in the story’s last line. The porosity of national borders, the interracial intimacies, the duplicities and disguises multiply out like waves rippling in the Sound.

The story was re-published as part of the Reclaim Her Name Project — a campaign spearheaded by Baileys (think: the chocolate-y Irish Cream) in conjunction with the UK-based Women’s Prize for Fiction. The Prize, which was inaugurated to correct the long-running gender imbalance of the prestigious Booker Prize and boasts such notable winners as Zadie Smith, Marilynn Robinson, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, is celebrating its 25th year. To mark the occasion, they hired a marketing agency to search out works of fiction published by women using men’s names.

Mahlon T. Wing was the moniker originally associated with “How White Men Assist,” but in the Reclaim Her Name version, the name “Edith Maude Eaton” is printed wide and white on the front cover. “Unlike her characters,” the boiled and brief frontmatter that accompanies the story reads, “she no longer needs to hide.”

But there’s a problem. Edith Eaton didn’t write this story.

Or, at least, we can’t say definitively that she did.

¤

The Reclaim Her Name project is now just a cul-de-sac of splash pages. Links promising to allow the eager internet surfer to “learn more” double back on one another endlessly, a slick succession of dead ends.

It’s a far cry from the laudatory bombast of the collection’s initial release just a few weeks ago. “Finally,” the website gushed exasperatedly, “giving female writers the credit they deserve.” Twenty-five e-books gleamed, ready for free download with satisfyingly color-saturated covers — reminiscent of Art Deco but with a sleek hipster twist.

The project’s missteps, however, quickly and cringingly outshone the veneer of spendy marketing and the feel-good glimmer of women getting their due. Activists and scholars pointed immediately to the problematic claims the collection made about authorial intention, gender identity, and historical representation. The British writer and critic Vernon Lee was deadnamed, and the inherent essentialism pointed to the transphobic bent of the project’s appeal. The cover of a biography of the famed 19th-century intellectual and abolitionist Martin Delany featured a portrait, not of Delany, but of his contemporary, the iconic Frederick Douglass. The racist mistake — interchanging one Black man with a very distinct other — was hurriedly corrected. There were dubious circumstances surrounding the acquisition of a manuscript by turn-of-the-century activist and writer Alice Dunbar Nelson. Scholars — many of them women — who had done the archival digging to make these texts available were obscured. Translators were unnamed. Context was scant. Even the collection’s title — a cavalier composite of California Congresswoman Maxine Waters’ viral demand “Reclaiming My Time” and the African American Policy Forum’s now ubiquitous #SayHerName campaign elided Black women’s labor. “Sloppy,” heralded The Guardian in what seems like an understatement.

¤

“Maybe I feel 60 percent certain,” Mary Chapman gave me her Eaton over-under on a recent Zoom call. Chapman, an English professor at the University of British Columbia, has studied Eaton for years.

Eaton is most recognizable to readers as Sui Sin Far — one of the many pen names under which she published. Mentioned in Frank Chin’s landmark 1974 anthology of Asian American writers Aiiieeeee!, Eaton has often been cited as an early example of Asian diasporic authorship in North America. But while she’s held some real estate on the revised, multiethnic cannon in literary studies, she’s still not a household name. That oversight — in part — can be attributed to a long-held estimation of Eaton as an episodic writer with a single collection of short stories that centered around a cunning Chinese immigrant woman, the eponymous Mrs. Spring Fragrance (1912). When Eaton was studied at all, she was understood as a writer of women’s lives and leisures, a chronicler of the small and domestic, an apolitical woman who was unable to make a serious career by her pen. “She was not a great writer,” wrote S.E. Solberg disparagingly in the 1984 MELUS article in which he reintroduced her to literary audiences, “She has only one book… but her attempts deserve recognition.”

Thanks to recovery efforts by Chapman and a handful of other literary scholars — Diana Birchall, Amy Ling, Annette White-Parks, June Howard, Martha Cutter, and more — that deeply gendered, A-for-effort dismissal is no longer defensible. Previously unattributed works filed under a multiplicity of evolving pen names continue to be discovered. Eaton’s bibliography has more than quadrupled in the last 25 years. We now know that she published hundreds of articles, essays, and short stories in nearly 60 popular periodicals throughout Canada, Jamaica, and the US between 1888 and her death in 1914. Eaton was not a dilettante, and she certainly wasn’t hiding.

Beginning in her hometown of Montreal, with stints in Ontario, Kingston, Jamaica, Los Angeles, Boston, New York, and Seattle, Eaton wrote travel narratives from horse carriages and train cars. She toured rum factories and poor houses serving up her hot takes for the press. She wrote ethereal poems of being “pinioned to earth” and dreamed up heart-rending stories of interracial love triangles. She argued against bicycle taxes and the anti-immigration laws that targeted Asians and Asian Americans. She — the daughter of a Chinese mother and white British father who smuggled immigrants from Canada over the US border — took an interest in the burgeoning Chinatowns on both east and west coasts.

It was Chapman’s conjecture that initially brought “How White Men Assist” under consideration as a possible work in Eaton’s oeuvre. Through a series of synchronicities in publishing and pagination, an inconclusive similarity between the byline and a known pen name, and the familiar subject matter, Chapman wrote in Becoming Sui Sin Far (2016) that the story “may have been written by Eaton” (emphasis mine). While there are certainly many echoes of Eaton’s frequent beats and formal innovations, there’s also significant reason to suggest that this piece may have been penned by somebody else. There’s no evidence that Eaton was ever in Victoria, British Columbia, Chapman points out, and while she may have swapped details out to appease a West Coast readership, would she have, for instance, been so intimately acquainted with the “small way house several miles out of the Esquimalt road?” Assigning the story to Eaton definitively without further substantiation risks potentially disappearing someone else.

Chapman’s two-sentence speculation is the only mention of a possible connection to Eaton anywhere. Notably, the Reclaim Her Name Project mentioned Chapman nowhere.

“This big fancy reveal erased my scholarship,” Chapman said, “it erased the provisionality, the speculation of my observation, and all the context that would have been helpful.”

Instead, Eaton’s case study — just one of the available object lessons produced by Reclaim Her Name — reveals the territorial avarice, white supremacist presumption, and archival unscrupulousness that animated this public relations mad grab. And it’s far from an isolated incident. Too often women, especially those marked by color and/or queerness, are trotted out as touchstones instead of regarded as serious cultural contributors. John Ernest, in another notable example, wrote in an issue of American Literature that the abolitionist and activist Sojourner Truth’s oft-referred-to-seldom-read autobiographical Narrative (1850) is, “both everywhere and nowhere in American literary scholarship.” Truth’s specificity-steeped story, her unconventional blend of literary genres, and the places where she refused to tell all, Nell Irvin Painter theorizes, left Truth “outside the canon” and made her “difficult for readers.” That meaningful difficulty is precisely what the Reclaim Her Name Project failed to recognize.

¤

“Why didn’t they reissue the Wing Sing travelogue?” asked Chapman with edgy disappointment on our call. “It’s beautiful.”

It is beautiful. It’s the choice of someone who has long-studied Eaton.

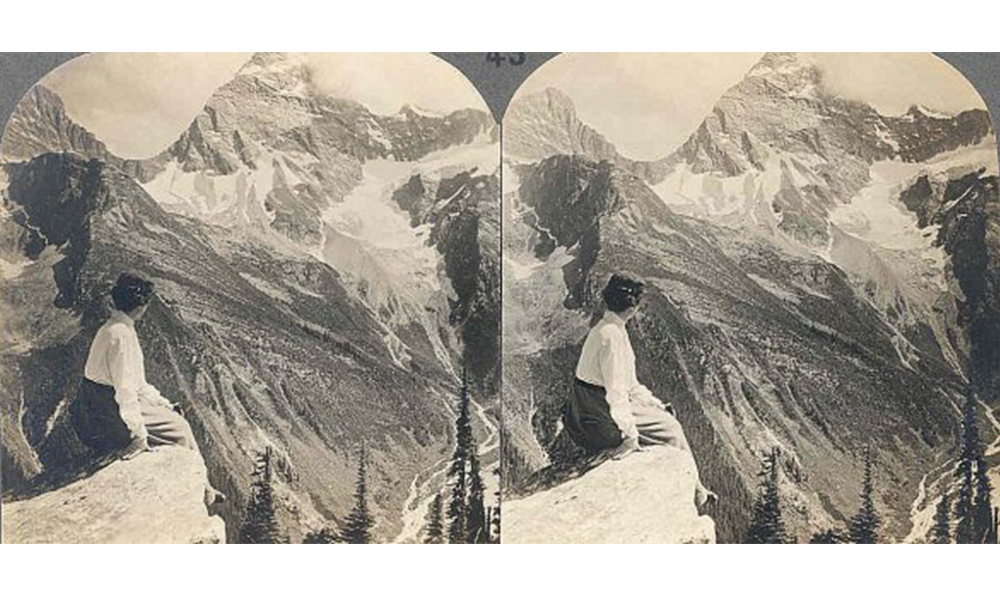

In the persona of Wing Sing — a Chinese businessman, long-living in Los Angeles and on his way to see a Montreal-based cousin — Eaton penned 15 dispatches from train travels up the California coast, across Canada, and back again through the continental US. It’s filled with practical information about overland travel in the early 1900s, side-splitting vignettes of an insomniac Irishman passenger, and succinct screes about racial prejudice. “[A man] go make up a wooden image in his head,” Wing Sing retorts after his wakeful traveling companion accuses the Chinese of being disinterested in technology, “and he call that a Chinaman.” In the same installment, Wing Sing speaks compellingly of the alpine landscapes of the interior of British Columbia. As the train passes through the remote trunk town of Revelstoke, the passengers can see “shining and high” the pyramidal glacier atop Mount Sir Donald. “My breath and my blood stand still as I look,” writes Wing Sing, and as a reader, you, too, suddenly feel the slow of your pulse and the suck of your inhale.

I don’t know the reasons the authenticated Wing Sing travelogue was passed over. But, my guess is that it’s because, like much of Eaton’s work, it is not easy. It, too, is difficult. The serialized sections alloy genres of travel writing and reportage with a little dash of short fiction. The syntax packs a clever political wallop but still transits in Orientalism. We’ll never know if Eaton cobbled her observations together from her own travels or if she donned men’s clothes and skirted North America as Wing Sing himself. “Sui Sin Far’s work was about inscrutability,” Xine Yao said at a recent roundtable convened to discuss the project, “Reclaim Her Name erases that, focusing on the revelation of identity and reifying the need to surveille.” And then, of course, there’s the thrill of conquest. By laying claim to a work not previously verified, Reclaim Her Name bought into the age-old settler colonial project of staking property and shoring up borders — the boundaries that Eaton was working so hard to circumvent.

¤

Archival work is all about muddled borders. To dig into the historical record honestly means capitulating the terrain of transparency. The task of recovery, Saidiya Hartman writes of transiting in the anemic paper trail of the Middle Passage, “has as its prerequisites the embrace of likely failure and the readiness to accept the ongoing, unfinished and provisional character of this effort, particularly when the arrangements of power occlude the very object that we desire to rescue.” There is no such thing as an easy reclamation.

More disheartening than the Reclaim Her Name Project’s unveiling was its disappearance. Rather than trying to rectify the oversights and errors, to include the scholars who had been obfuscated, to concede the always partial gaze of women in the archive, the organizers simply shut the site down. They refused to dwell in the complexity of Eaton, in the difficulty of her compatriots, who pushed the limits of the ways in which their world tried to keep them bound.

Some moments and miles after his encounter with the gelid glacier, Wing Sing is awed by its compatriots. He beholds yet more mountains — the grandeur of the Selkirks to one side and the snow-capped Rockies on the other. He reaches the limits of language and reminds us that some ways of being and feeling elude representation. “My expression,” the final line reads, “it not express me.”

Top image: Mt. Sir Donald, the Matterhorn of the North American Alps, British Columbia, Canada. Image courtesy of Keystone-Mast Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside.