“A setback can be a setup / for a comeback, if you don’t let up.”

(Purple Mountains, “That’s Just the Way That I Feel”)

When I got a text from my friend Sam that said “holy fucking shit David Berman,” I hoped it was about Berman’s new record.

Sam and I are members of a small but devout group of superfans who treat the work of songwriter, poet, and cartoonist David Cloud Berman like gospel. We don’t talk all that much, but we bonded over shelling out an unreasonable amount of money for a used copy of Berman’s then-out-of-print, beloved, sole poetry collection, Actual Air. For us, every rare emergence of Berman into the public sphere was a major event. We took what we could get: Berman only ever toured twice, and, particularly at the start of his career, he rarely gave interviews. We would treat a blurry photo of Berman at an art opening, posted deep in some fan forum, with the rapture fans of more conventionally public musicians would treat a concert or album release.

2019 was for Berman fans what Jerry Garcia coming back from the dead would be for Deadheads — up until August 7, 2019, that is, the day Sam texted me. In 2009, Berman called it quits on his band the Silver Jews. A musician’s retirement often is little more than a publicity stunt, but for someone as reclusive as Berman, it felt more believable. After nearly a decade of (mostly) radio silence, out of nowhere, in May 2019, he announced a comeback single under the name Purple Mountains. Following the single came the unlikeliest thing that a Berman fan would ever expect: what appeared to be a traditional, modern-day album rollout press cycle. He did not just a couple, but many interviews. He took over the Instagram of his label, Drag City, for a day. He did a Reddit AMA. Against truly all odds, he even announced a tour. The record came out. It was some of his best work.

Though Sam had every reason to text me “holy fucking shit” about Purple Mountains, it was strange that he texted me a month after the record’s release. Sam didn’t say why he texted. Just “David Berman,” the two words I hurriedly Googled as soon as I got the text.

¤

“But mostly I wish / I wish I was with you.”

(Silver Jews, “Death of an Heir of Sorrows”)

In a 2005 interview with The New York Times, David Berman said of football player Joe Montana: “He was successful because he didn’t try to do what he couldn’t.” Of himself: “I couldn’t rock out harder than everybody… so why try? That’s why I’ve always worked harder on words.” It’s not long into any Berman record before you hear his scratchy, deep voice — sonic proof that he spent more time on his lyrics than on his technical singing ability. He always had a knack for album-opening lyrics. 2005’s Tanglewood Numbers begins: “Where’s the paper bag that holds the liquor? / Just in case I feel the need to puke.” He sounds like the type of person who might be desperate enough to ask this question, not so much like a conventional rockstar.

Berman’s music proves he didn’t try to out-rock anyone. After the rockier sound of their debut album Starlite Walker, with records like The Natural Bridge and American Water, the Silver Jews settled into the sound that would stick: a subtle, country-inflected indie rock that reflects and enhances the tone of Berman’s lyrics. The music’s simplicity creates space for the lyrics to breathe. Breaks from that simplicity — a guitar solo, an instrument other than guitar/drums/bass — intensifies the feeling of the words. Berman understood the emotional resonance of each note, chord, and instrument in his songs, and how they danced with his lyrics.

Take “Trains Across the Sea.” It alternates between two simple major chords, F and C. But the little flourishes of piano and bass burst through the steadily strummed guitar like streaks of sun on an otherwise cloudy day. The music drives home the song’s sentiment that there might be hints of a better life, but the speaker isn’t really feeling them:

In twenty-seven years

I drunk fifty-thousand beers

And they just wash against me

Like the sea into a pier.

As other writers have noted, Berman wrote images that make you see things differently. (“Well the water looks like jewelry / When it’s coming out the spout”; “The jagged skyline of car keys”; “My horse’s legs look like four brown shotguns.”) Though I’ve always loved Berman’s uncanny ability to find surreal, associative beauty in the otherwise everyday, I prefer his more direct lines. They’re like diamonds formed under the pressure of his more obtuse style. Take this verse from “Black and Brown Blues”:

It’s raining triple sec in Tchula

And the radio plays “Crazy Train”

There’s a quadroon ball in the beehive

Hanging out in the rain

And when there’s trouble I don’t like running

But I’m afraid I got more in common

With who I was than who I am becoming

After hundreds of listens, the meaning of raining triple sec still escapes me, and I don’t know why it’s important that “Crazy Train” is on the radio. But I get a sense that it is directly from this imagery — not a throat clearing, more of a tone-setting preamble — that we get, “And when there’s trouble I don’t like running / But I’m afraid I got more in common / With who I was than who I am becoming,” a collection of words that so succinctly describes the pain and fear of change. As a 21-year-old, this verse hits me like a gut-punch every time I hear it.

But it’s hard to be optimistic when you’re a Berman fan. His first real profile, published in The Fader in 2005, wrenchingly depicts Berman’s longstanding struggles with addiction and what he would later call “treatment-resistant” depression. In the piece, Berman talks about attempting suicide in 2003 by intentionally overdosing on crack and 300 Xanax. When he retired, his reasoning was so convincing, too. He said that he’d kept his greatest secret from his fans for too long: “worse than suicide, worse than crack addiction: My father.” He’d put, in part, the energy he poured into the Joos (fan-preferred spelling) to righting the wrongs of his deeply evil, powerful conservative lobbyist father. 60 Minutes once did a segment on Richard Berman called “Dr. Evil.” Berman called the blog post “My Father, My Attack Dog.”

My skepticism that Berman would return to music ran so deep that even when I heard in May that he would be releasing a vinyl-only single, I thought it would be a one-off, living only in record-store obscurity, a loosie just hinting at the comeback that might have been. But once I got a YouTube notification for the “All My Happiness Is Gone” music video, a week after the announcement of the single (I went to every record store in Cambridge hoping to find a copy), I had to face it: he really was back. The video starts with wordless hums and hesitant, plucky guitar, lingering on two qualities Berman typically hides behind his lyrical prowess: his off-key baritone and his sometimes-shaky guitar playing. The song, with its vocal-instrumental intro, transitioning into its major-key, synthy splendor, sounded like his return felt: unlikely, and then glorious. Of course, in hindsight, I should have been smart enough to hear the lyrical content. He says outright, “I confess I’m barely hanging on.” The song is called “All My Happiness Is Gone.” I selectively heard only the sound of my hero coming back, not the warning of his premature departure. Soon after the video came a release date for an entire new record and, even more surprisingly, a tour.

The week Purple Mountains came out, I pitched a review to BLARB. I injected lots of narrative into the pitch — how it was his first record in ten years, how in the lyrics Berman managed to bridge the directness of the blog post announcing his retirement with the beauty of his more abstract Joos imagery. After writing the pitch, I even arrived at an opinion I hadn’t seen elsewhere: the record is a lyrical breakthrough, a move to a confessional stage as yet unseen in Berman’s body of work. But it wasn’t, I thought, as much of a musical breakthrough: the highly produced feel to these new songs made me miss the scrappiness of The Natural Bridge, the charming, uncertain honky-tonk of Tanglewood Numbers. Still, I thought, with the record and its rollout, it felt like Berman was acknowledging the incredibly strong relationship his fans have to his words and music. He made in-references for the first time, with the record’s beginning, “Well, I don’t” referencing the opening lines of The Natural Bridge (“Well I don’t really wanna die / I only wanna die in your eyes!”), and the “I loved her to the maximum” of “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son” referencing “I loved you to the max!” in “Punks in the Beerlight.” For someone who was notoriously reclusive, it felt like he was finally accepting his connection with his devoted fanbase, his connection with people like me.

Purple Mountains, lyrically, is like Berman ran with the directness of my favorite Joos lines and made a whole album of them. This is an entire album where the “I,” for the first time in his discography, is always, unmistakably Berman. It sounds like he finally made good on the promise of his fan-favorite poem, “Self Portrait at 28”: “I am trying to get at something / and I want to talk very plainly to you / so that we are both comforted by the honesty.” That sometimes-strange imagery now feels in service of clarity and precision. For example, in “Darkness and Cold”: “The light of my life is going out tonight / in a pink champagne Corvette / I sleep three feet above the street / In a Band-Aid pink Chevette.” The brutal contrast between the “champagne Corvette” and “Band-Aid pink Chevette” draws listeners right into the pain of the song’s topic, Berman’s separation from his wife and former bandmate, Cassie.

In the lyrics, which I could sing by heart by the end of the weekend of the record’s release, I focused on the signs of hope. Take the opening track, “That’s Just the Way that I Feel”: “A setback can be a setup / for a comeback, if you don’t let up.” The next line is: “But this type of hurting won’t heal,” and the one after that, repeated as a refrain: “The end of all wanting / is all I’ve been wanting.” I chose not to hear that part. I agreed. A setback could be a setup for a comeback. The setback, a decade of depression and isolation, was clearly a setup for the comeback: this record, a tour.

“Nights That Won’t Happen,” the most devastating song on the album, has another bleak refrain: “The dead know what they’re doing when they leave this world behind.” I was optimistic enough to read the title as an admission of triumph, that sad nights won’t happen to Berman anymore, because he’s coming back — because if someone like Berman can come back, get better, after all his suffering, maybe I can deal with my own.

I bought tickets for the Cambridge show the moment they released. I still have the confirmation email pinned in my e-mail inbox. Looking at the tickets, I fantasized about singing along to the lyrics of my favorite Joos songs, lyrics that put words to feelings I couldn’t previously name, lyrics that described the mundane in its hallucinatory, strange beauty, lyrics that found that beauty in the darkest places, lyrics that might, maybe, somehow, have taken on even more meaning if I sung them with other people who love them, and love him, as much as I do. Lyrics that might mean more to the lyricist if he saw how much they affected people like me.

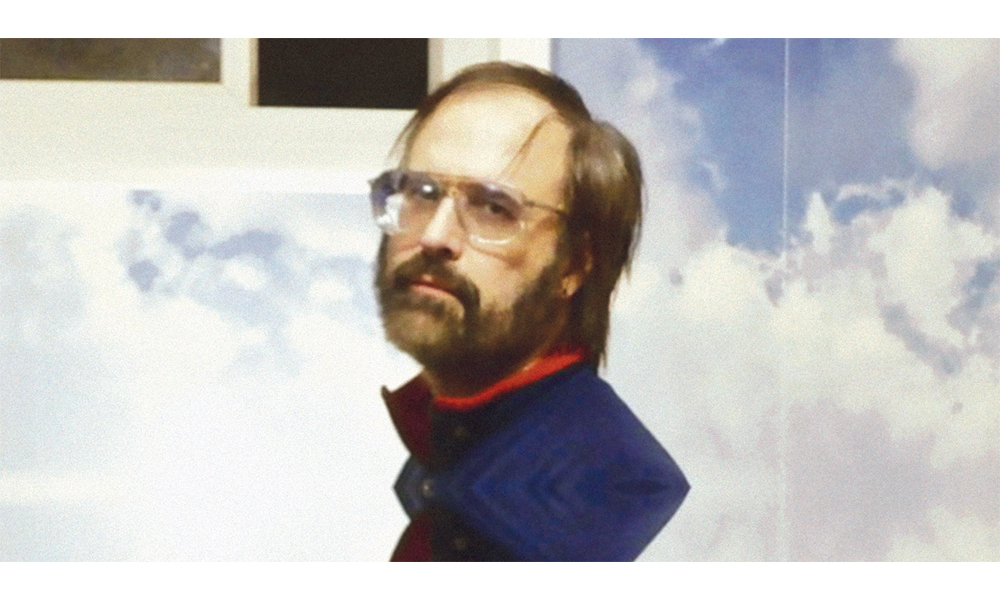

I imagined the concert. I saw his receding hairline emerge from backstage, with his Western-tinged wardrobe in tow, his sallow, angular face, lit up by the thing he probably hated the most: the spotlight. His big, blocky sunglasses, too. I couldn’t believe I’d be able to sing his songs with him. In an interview with The Ringer, he even said he would speak to anyone who stayed after the show. I fantasized about staying late at the venue, The Sinclair, scouring the streets outside for the tour van, just to say something, anything about how much his music, his poetry means to me. All I wanted was to look him in the eye and tell him.

¤

“It’s been evening all day long.”

(Silver Jews, “Trains Across the Sea”)

Sam texted me “holy fucking shit” because David Berman was dead. A couple days later, The New York Times confirmed the inevitable: death by suicide. Words and images and melodies from across his discography flitted in and out of my mind like songs from a broken, one-man jukebox. The “Nights that Won’t Happen” — how could I be so stupid? How could I not hear this? — were the nights of the rest of his life. Listening to his music now, death and suicide cloud his discography: “And you got that one idea again / The one about dying” (“Slow Education”); “We’d never been promised there’d be a tomorrow / So let’s just call it death of an heir of sorrows” (“Death of an Heir of Sorrows”); “Final words are so hard to devise” (Pretty Eyes”). It’s tempting to listen to the record and hear less of a comeback and more of a suicide note.

Purple Mountains does have lots of lines about wanting to die, sure. But it also has so many jokes: “If no one’s fond of fuckin’ me, maybe nobody’s fuckin’ fond of me” (“Maybe I’m the Only One for Me”); “I nearly lost my genitalia to an anthill in Des Moines” (“That’s Just the Way That I Feel”). And the record even has almost self-helpy yearnings to be better: “I’ll put my dreams high on a shelf / I’ll have to learn to like myself” (“Maybe I’m the Only One for Me”). One song, “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son,” the first he wrote for the record, is a spare, plainspoken, sweet tribute to his late mother. “When she was gone, I was overcome / The simple fact left me stunned / I wasn’t done being my mother’s son / Only now am I seeing that being’s done.” These lyrics all, I think, resist the reading that this entire record is a 44-minute suicide note. For this reason, I trust Drag City when they say, “Some of his incredible turns of phrase seem to have been written for this awful moment. But know that they weren’t. They were written in lieu of this moment, to replace this moment, showing the world (and himself) that maybe he didn’t truly know what was going to happen next.”

Behind the death cloud, there’s still a blue sky. In his music there is also God. There are dogs. There is the sea.

¤

“Promise that I’ll always remember your pretty eyes.”

(Silver Jews, “Pretty Eyes”)

Silver Jews and Purple Mountains were my #1 and #2 most listened-to artists on Spotify this year. My 2019 Spotify wrap-up asked me, in a bouncy, animated sans sarif font, to “Tell this artist how much they mean to you!” The words danced above his scowling and pensive face. The crass obliviousness of the Spotify algorithm was both sad and darkly funny. It felt like an image Berman would have written.

Berman obituaries and post-death thinkpieces claim that Berman’s work did things like “made us feel less alone” and “changed the way so many of us see the world.” He made us feel less alone and he changed the way we see the world by making us see the world like he did. He relentlessly brought his readers and listeners into life as he experienced it, through lines as elliptical as, “In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection” and as direct as, “I loved you to the max!”

I now imagine even his more abstract imagery as confessions, a kind of sincere surrealism. Even Berman’s occasionally obscure images paints a more complete picture of what it was like to see the world through his eyes, how scary and strange and surreal the everyday is when most every day is a question if you’ll make it to the next one.

Berman put this better than I ever could, in a much-quoted passage from “Snow is Falling in Manhattan”:

Songs build little rooms in time

And housed within the song’s design

Is the ghost the host has left behind

To greet and sweep the guest inside

Stoke the fire and sing his lines

It devastates me that everything I’ve written in this piece is based only on the “ghost[s] the host has left behind,” that I’ll never know the host himself, that I was so close.

Writing this piece, I rewatched the “All My Happiness Is Gone” music video on a big television. During the parts where Berman looks right at the camera, I stared into his eyes and sang along. Our heads were about the same size. I don’t have a very good singing voice, but neither does he. Our voices are deep, they blended together. It felt like we were singing together, and to each other.

The day he died, I spent a while on Twitter, reading memorial thoughts from fans, major musicians, and journalists alike. Replying to the official Drag City tweet announcing Berman’s death, a fan told a story of sending Berman his music. Berman replied in chickenscratch scrawled on an old used boarding pass. I wish, so desperately, that Berman could have listened to his own advice.

“Keep going. It’s going to take a while.”

¤

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. Here are resources if you’re outside the US.

For more, here’s a link to Berman’s blog, a Spotify playlist I made with my personal favorite Berman songs (heavy bias towards The Natural Bridge), and a great piece from Stereogum on The Natural Bridge. And, of course, a wonderful essay on Berman published right here in LARB, by Ava Kofman.