In 1928 a forensic examiner named Harrison Martland published a famous paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It was titled “Punch Drunk.” It is often said to have introduced medical readers to an occupational disease caused by recurrent hits to the head.

Called now chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE, “punch drunk,” Martland said, originated in boxing slang. In his hands, it evolved into a clinical entity.

In the history of concussion research since Martland published his classic studies, many authorities have fixated their interests on the fact that Martland was reporting an occupational disease in boxers.

In fact, Martland’s study was more ambitious than that. He was directing attention to the way that boxers could reveal pathologies from even mild hits to the head in anyone who had been hit in the head, even once, but especially if the hits were repeated.

As an historian of neurology writing a book on the history of modern violence and brain trauma, I am frequently fascinated by journalism and scientific writing that treats the head impact medical problem in sports as a new topic, one just now emerging. It is an old problem.

Researchers and journalists today rightly look towards new trends in science, medicine, and engineering. From that viewpoint, 1928 certainly does seem a long time ago. Yet, I think one of the reasons that Harrison Martland’s 1928 study so often surprises people when they first encounter it is the shock that this scientific concern about recurrent head impacts dates to so long ago.

In fact, the documentary evidence for that knowledge from the past is far wider and deeper than is today widely appreciated.

The results of Martland’s research had first been reported in a 1927 paper read at the American Neurological Association meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Martland and his collaborator Christopher Beling reported on a series of 309 autopsies of traumatic brain injury. The report included a clinical description of a man named H. D.

A shipping clerk and boxer, H. D. was all of 22 years of age. H.D. had received “many blows on the head and face while boxing.” He had also been hit on the head with a blackjack. Nine months after the blow with the blackjack, H. D. had begun to show signs of disease. He had, Martland and Beling said, a post-traumatic parkinsonian syndrome.

H.D. had been committed to hospital “after several attempts at suicide”. There Martland said he was “irritable, depressed at times, emotionally unstable, and impulsive”. H. D. fit the profile of what Martland would argue a year later in his 1928 paper was the consequence of recurrent concussions. H.D. was punch drunk.

Documents from collegiate sports authorities also illustrate how common knowledge about these problems was in the past. (In the spirit of full disclosure, I am retained as a testifying expert witness in cases pending against the NCAA and other organizations.)

During the course of the famous concussion lawsuit against the National Football League, a copy of the National Collegiate Athletic Association Medical Handbook for Schools and Colleges turned up. It was published in 1933. Public copies exist at the New York Academy of Medicine among other libraries.

The authors of the 1933 NCAA medical handbook were Edgar Fauver, August Thorndike, and Joseph Raycroft. These were pioneers of sports medicine, and Thorndike would become especially illustrious.

The NCAA appointed these physicians in 1933 to “study and report on the general subjects of training and medical supervision of athletic squads.” In the manual, the doctors wrote “there is definitely a condition described as ‘punch drunk’ and often recurrent concussion cases in football and boxing demonstrate this.”

Documentary evidence of this kind was fairly common, and I have located many compelling examples.

As part of my research, I often scour e-Bay for hardcopy versions of old magazines and periodicals for my growing personal archives on violence and brain injury. One document I recently purchased on eBay was The Official 1944 Boxing Guide of the National Collegiate Athletic Association.

In this guide, Alfred Griess, then team doctor at Penn State College, took up the question of whether boxing opponents were right.

Griess wrote that “punch drunk” was not common among amateur boxers. He observed, however, that “cases had been cited to occur among wrestlers, professional football players, victims of automobile or industrial accidents, etc.” He also said, “This pathetic condition may occur in any activity which causes jarring of the brain.”

Similarly, I recently located an undated faculty report (from before 1950) of the development of intercollegiate boxing at the University of Illinois. That document included the results of a survey of neurologists and psychiatrists, with 46 responding.

When university faculty asked neurologists and psychiatrists “can repeated blows on the head over a period of two to four years cause a gradual change in mental pattern, etc., of the individual?,” 76% of the respondents then asked said “yes.”

As these early examples (all appeared before 1950) show so well, doctors and sporting authorities understood in those days that repeated blows to the head are dangerous and sometimes caused clinically observable illness.

Since 1950 reference materials, medical textbooks, dictionaries, and even diagnostic manuals have defined and described occupational illness resulting from violence to the head. For all of that, sports players and coaches have struggled to appreciate the risks of recurrent head impact violence. Denial starts at that level.

A 1985 textbook entitled Principles of Sports Medicine by W. N. Scott, B. Nisonson, and J. A. Nicholas is one example. It describes a community college coach glibly unaware that one of his players was showing severe deterioration from cumulative concussion as well as early clinical hallmarks of becoming “punch-drunk.” It is easy to speculate that the brain-injured player was even less aware of these facts.

Some players probably did wonder if they were merely disposable bodies and brains, although it is hard to find such recognition recorded in primary sources.

In an astonishing profile by Alex Poinsett that appeared in Ebony Magazine in 1964 of American footballer and fullback Jim Brown, described as football’s mightiest player, Brown recalled one time when he had a significant cerebral concussion resulting in amnesia at the sideline.

His coach, Brown said, seemed to think he was faking and wanted him to get back into the game. To Brown it was clear that the coach “didn’t seem to care if you lived or died, so long as you played.”

Is the elite game so different today?

Since the NFL Concussion Settlement in 2013, it has become common for doctors and psychologists to clarify strenuously that the occupational diseases resulting from careers of recurrent head injury exposure can only be diagnosed post-mortem. I sometimes speculate about whether there is a cultural and historical relationship between those denials and the way the settlement sits as a background feature to all investigations and policy discussions about brain injury and head impact.

Meanwhile, it is not uncommon to find seminars and publications for clinicians that argue that research on chronic traumatic encephalopathy remains in its infancy. It should not be lost on us that there is a deep irony in that observation. Scientists obviously know far more today about CTE then Martland and Beling did in 1927. Yet where Martland and Beling could clinically characterize their patient H.D. without debate, today some doctors appear unable to do so for their patients with similar life histories.

What has happened in the intervening years since 1928 is a longer and complex story about a struggle for truth. Sadly, that struggle for truth has not come with warnings. There is no reason those warnings cannot be given today.

If CTE research is truly in its infancy, then there is reason enough to use prevention as a means of making sure it never grows up.

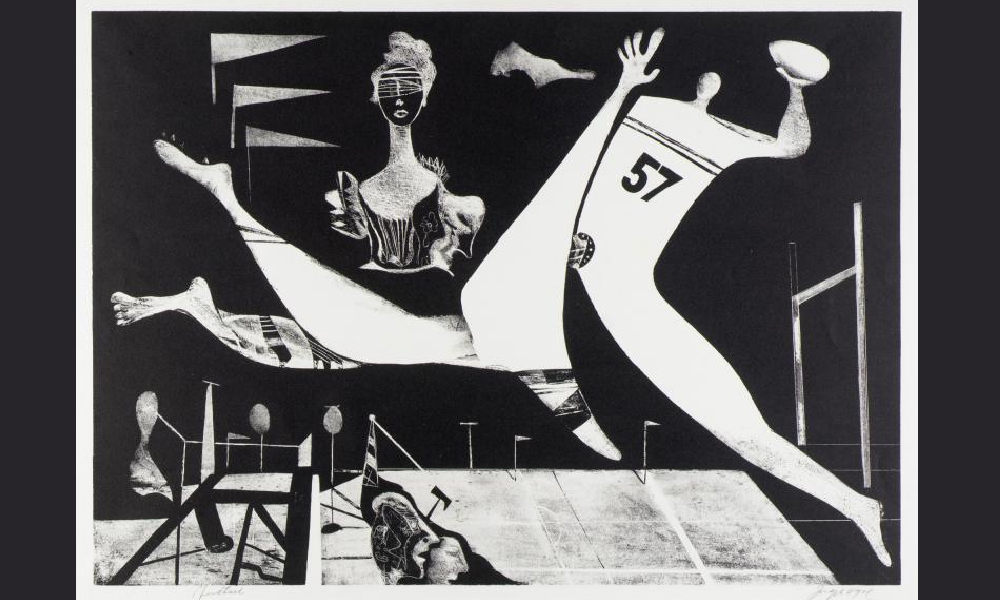

Image credit: Joseph Vogel. “Football.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Audrey McMahon.