Had he died during the 1960s, instead of living until 2008, to die of heart failure in Moscow at the age of 89, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the 1970 Nobel Laureate for Literature, would have been remembered as a hero, a prophet, and, above all, a great writer from a country of great writers.

But he made one crucial mistake; he survived. And not only did he survive World War II, Stalin’s labor camps, and stomach cancer, he outlived communism.

By the time Solzhenitsyn had settled in Vermont in 1976, where he lived in a high-security compound, the West had already discovered a far more attractive Soviet dissident — the poet Joseph Brodsky, who openly performed the role of artist, played to the gallery, and would eventually, in 1987, also be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Solzhenitsyn, reclusive and taciturn by nature, was very different. His soldier father, having returned from World War I, died in a hunting accident six months before the future writer’s birth. Some suggest the death was a suicide, but whatever the truth, Solzhenitsyn was born in the shadow of a family tragedy and was left with relatives while his mother went to work in a nearby town. He was also born into revolution; his birth on December 11, 1918, in Kislovodsk, a Russian spa town in the Caucasus Mountains, occurred just over a month after the first anniversary of the Bolshevik takeover, and in the midst of the ensuing Civil War.

The young “Sanya” Solzhenitsyn was clever, securing a first-class honors degree in math and physics while pursuing his interest in the arts, particularly literature. Soon after, he was called up. Already something of an intellectual, he proved an arrogant soldier, keeping himself aloof from his comrades while serving as a gunner. Twice decorated, he quickly progressed to captain. Then he made a mistake; when writing a letter to a friend, he included “derogatory” comments about Stalin. The irony was cruel, but not unusual: having served his country heroically, Solzhenitsyn was arrested as an Enemy of the People in early 1945. He served his eight-year sentence in the hell of the Gulag labor camps, where political prisoners lived alongside criminals.

These experiences inspired a masterful debut, the short novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Initially published in the November 1962 issue of the Russian literary journal Novy Mir, it made his name and remains, perhaps, his finest artistic achievement. One Day sent shock waves around the West, confirming fears that what had happened in Stalin’s Soviet Union was analogous to what had happened in the Nazi death camps. In reality, millions of Soviet citizens had perished in the Gulag system, suffering a fate even worse than that of Solzhenitsyn’s central character.

Written in a laconic, bleakly lyrical third person voice that is both heartrending and, at times, deeply witty, Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece is a human document like no other. Having retained his sense of honor, Ivan Denisevich survives, at least for one long day, the biting cold, the hunger, and the dictates of an inhuman, often farcical system. Each time one reads the novel — like Albert Camus’s The Stranger or Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, it demands rereading — its narrative power resonates. One touching scene hints at the sources of Ivan Denisovich’s resilience. When speaking to a doggedly rational fellow prisoner, Captain Buinovsky, who has been imprisoned for the “crime” of having been liberated by American forces, our hero asks him where the old moon goes after dawn? Buinovsky thinks the question ridiculous. So Ivan Denisovich educates him: “In our village, folk say God crumbles up the old moon into stars.” These new stars then fill gaps left by stars that have fallen, exhausted, from the heavens. It is this magical thinking, this imaginative view of the world that sustains the exhausted man.

On his release from the camps in 1953, Solzhenitsyn was sent into internal exile in a village in Kazakhstan, where he faced another ordeal, cancer. A late diagnosis left him close to death. Eventually allowed treatment, he travelled to a hospital in Tashkent, where he went into remission. This experience would later inspire another compelling narrative, Cancer Ward, and at the same time he completed a larger novel of the camps, The First Circle, which focused on the life of imprisoned scientists and academics. Both were published 1968, but only abroad, not in the Soviet Union. This did not please the authorities, and his next move proved even more provocative.

Solzhenitsyn the artist was fast becoming Solzhenitsyn the campaigner. Setting out to expose the horrors of the Soviet system he began his monumental work, The Gulag Archipelago, the defining history of the political oppression that destroyed millions of Russians. Its three volumes are testimony to his personal courage, as well as his love of his country. The entire text, which runs to more than 1,500 pages, was completed by 1968 and smuggled out of the country. In retribution, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers’ Union in 1969. The next year, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Retribution for that may have come in the form of an attempted assassination by the KGB; in August 1971, Solzhenitsyn was fell seriously ill, after a possible poisoning.

His conflict with the Soviet leadership eventually led his expulsion from the state. In February 1974, he was arrested and deported, arriving in Frankfurt, his first safe harbor, and then moved to Cologne, where he lived in the home of fellow Nobel Laureate Heinrich Böll. Solzhenitsyn later moved on to Zurich and, finally, to the United States, where he was to remain, without ever assimilating, for almost 20 years.

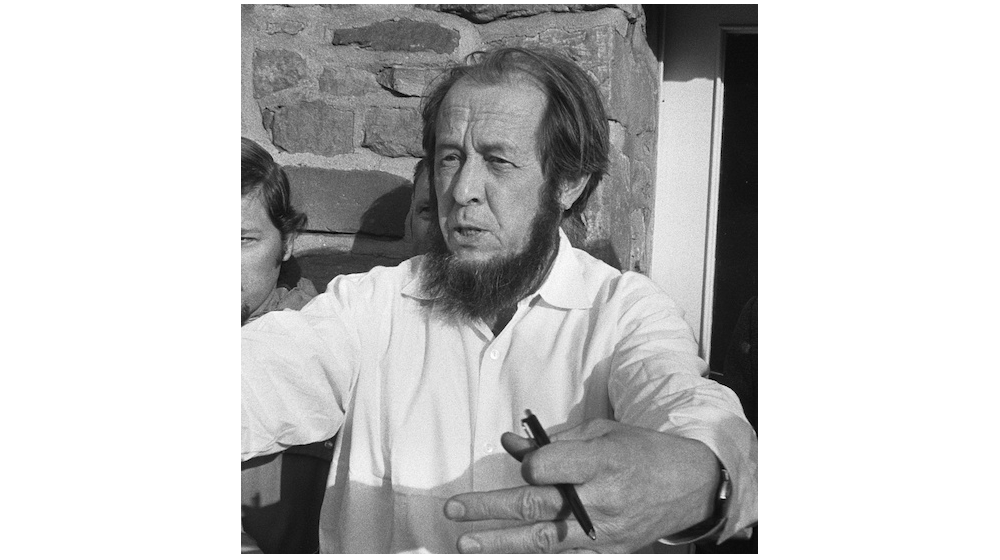

There is no disputing his contribution towards the collapse of Soviet communism: he had exposed the system’s murderous cruelty and hypocrisy. And while his fiction and documentary writing were being read all over the world, he was grimly devoting himself to the story of Russia. The witness, the writer, had become an historian. No longer regarded as a persecuted prophet, he was increasingly dismissed as a polemicist and a crank. His personality did not help: he was notably cantankerous. Years of hardship, constant pressure, and ill health had left him wary, even suspicious, and difficult to approach on a personal level. His severe manner and straggly monk-like beard combined to make him look like a medieval figure, straight out of central casting.

In 1994, three years after the fall of the Soviet regime, he decided to return home — to a changed country, which greeted him with indifference rather than affection. Younger people regarded him as a dinosaur. Solzhenitsyn had outlived his time, yet his achievement remains. The prophet may have been forgotten, the historian overtaken, but the novelist will endure, thanks to a short novel that strikes deep at the very heart of what it means to be human.

A version of this tribute first appeared in Eileen Battersby’s Second Readings: From Beckett to Black Beauty (Liberties Press, 2015).