There is a famous essay in the history of modern art called “The Monuments of Passaic.” Written in 1967, its author, Robert Smithson, takes us on a journey back to his home state of New Jersey, documenting various “monuments” as he goes.

Smithson’s monuments are not of the conventional sort. They consist of old pumping derricks, abandoned sandpits, and random industrial offcuts. Indeed, his point is not so much to provide a survey of the state’s statuary, but rather to define what a new monument for a post-industrial America might be.

Figure 1: Robert Smithson, “The Monuments of Passaic,” Artforum, 1967.

New Jersey might not seem the most obvious state to begin this inquiry today. The monument-dense mall of Washington or the statue-laden cities of the South appear readier candidates given the selective histories their monuments represent. Yet, just down the road from Passaic, in the city of Newark, four local artists have, like Smithson, returned to address this very theme.

At the edge of the city’s Military Park, one of the country’s oldest greens, there is a very large collection of rubber tires. They are squashed down and bolted together but still rise well above head height. It is not immediately apparent but, if you follow the shape, you’ll find they form a giant question mark. The punctuation is fitting: public art is often met with questions — most often, what is it?

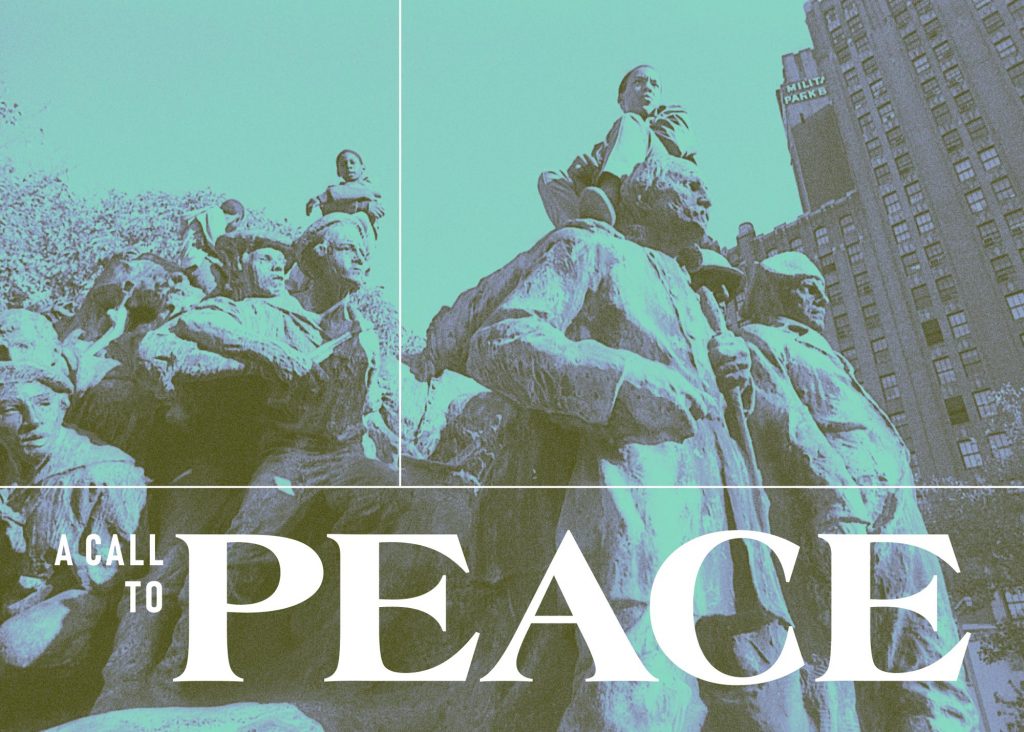

Figure 2: Chakaia Booker, Serendipity, 2019.

The sculpture is called Serendipity, by artist Chakaia Booker. At first glance, it might pass for one of Smithson’s monuments. The title similarly conveys delight in finding value in the unexpected or unintentional. Booker often uses discarded tires as her material, building them up to large, impressive scales. Her sculptures welcome and reward curiosity, but are far from isolated objects. They engage with the place in which they’re put and the people present there or passing through. In Newark’s Military Park, this quality is particularly clear. Here, Booker’s question mark is more directed than self-reflective. It is placed parallel to the park’s central monument, Wars of America.

Wars of America dominates the park’s landscape. It consists of 42 bronze figures sprawled across a large granite base that form the handle of a giant sword when viewed from above.

Figure 3: Military Park (Aerial View).

The monument is problematic for several reasons. Its sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, was closely associated with the Ku Klux Klan and his correspondence reveals that he shared their racist views. Although most famous for the colossal carvings on Mount Rushmore, Borglum was also responsible for designing the country’s largest Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, a site with strong links to White Supremacy, both then and today.

Yet, more than an objectionable sculptor connects Georgia and Newark. The granite that forms the base of Wars of America derives from Stone Mountain, too. Indeed, Borglum’s involvement in both projects encourages us to read its use symbolically as an assertion of White Supremacy. This inference is supported not only by the sculptor’s political inclinations but by the fact that of all 42 figures, not one is black.

It is this selective vision of the past that Booker’s Serendipity questions. Hers is one of four prototype monuments created for the month-long exhibition A Call to Peace. Devised by the Philadelphia-based public art and history studio, Monument Lab, and the local art and activist organization New Arts Justice, A Call to Peace is driven by a specific question of its own: What is a timely monument for Newark?

Figure 4: A Call To Peace Exhibition Banner, 2019 (Image: Manuel Acevedo).

The word “timely” is critical. Traditionally designed to last, monuments have tended to acquire a reputation of being “timeless.” This is misleading, for they are of course full of time. Objects associated with memory cross the tenses. Monuments conjure the past in the present and are accompanied by the imperative not to forget. Acknowledging the timeliness of monuments forces us to reflect on current values and their expression in public space.

It is often the case that the longer monuments have been in a place, the more they can get away with. Their age becomes a value of its own and they become part of a general landscape that is too often cast as separate from us. In other words, we become habituated.

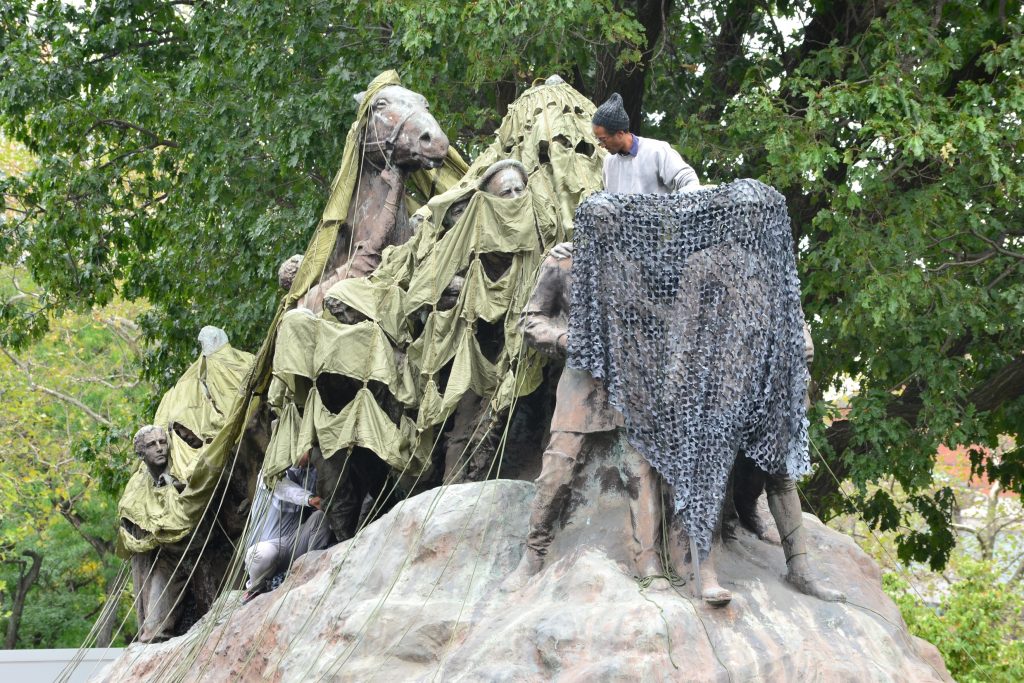

Figure 5: Manuel Acevedo, CAM-UP, 2019 (Photograph: Diana Diaz).

Wars of America has been in Military Park since 1926. At nearly 100 years old, the monument has been a constant in the lives of most Newark residents. For the Newark native and multi-media artist Manuel Acevedo, it has also been a source of continual engagement. Since the 1980s, Acevedo has documented the site and the transient events that have occurred there. First attracted to the sculpture’s larger-than-life figures and their physical arrangement in space, Acevedo explains that he was “intrigued by the social juxtaposition inherent in Military Park” and the failure of the monument to “reflect the local community” that gathered there. (Manuel Acevedo, A Call to Peace Newspaper, pg. 6)

In his contribution, “CAM-UP”, Acevedo plays on this failure to reflect. The work consists of a series of “happenings” during which the artist covers Wars of America with various materials or “camouflage veils.” By using camouflage to foreground an object rather than make it blend in, the performance creates an effective irony that forces us to reconsider things we might otherwise ignore. In this case, ignorance, in both senses of the word, has social repercussions. Wars of America’s selective telling of the past, and our acceptance of it, mirrors much broader issues of unequal representation.

Sonya Clark and Jamel Shabazz’s prototype monuments also address this imbalance. Clark’s Monumental Fragment recreates a section of the little-known “Confederate truce flag,” a cloth used to signal the surrender of the South and end of the Civil War. The fragment forms part of Clark’s larger effort to popularise this flag and its message which is, quite aptly, “a call to peace.”

In Shabazz’s Veterans Peace Project, we are reminded how national narratives and local ones interact. Returning us again to Newark, Shabazz photographed local Veterans who served in subsequent “wars of America.” Confronting Borglum’s monument, large portraits of Vietnam Veteran Larry “Free” Dyer and Jillian M. Rock, the daughter of the late Vietnam Veteran Jerome Rock, speak to a different generation. Their portraits call on us to invest in the lives of individuals whose stories are rarely told.

Figure 6: Jamel Shabazz, Veterans Peace Project, 2019.

This is just one of the reasons a participatory research lab can be found next to Borglum’s monument: A Call for Peace asks everyone to imagine a new monument for Newark. Whether an impressive pumping derrick à la Smithson or a more traditional statue form, the monument proposals the lab collects work towards a vision of public space more inclusive in scope but no less inquisitive in action. As Booker’s proposal literalizes, monumental landscapes must be held in constant question.