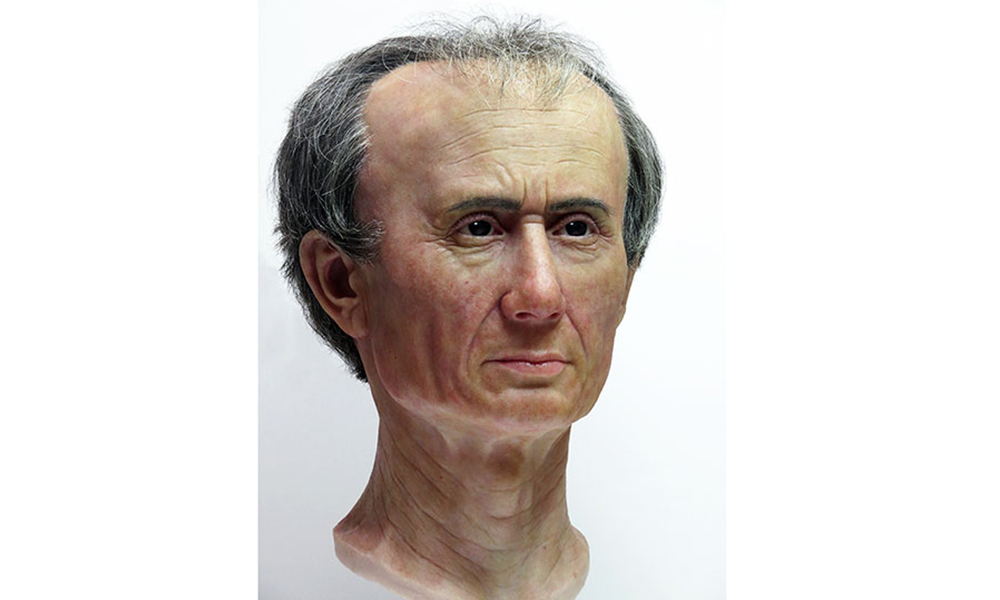

Reconstruction of Julius Caesar above courtesy of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities.

What would contemporary mental health professionals make of Cato the Younger, who committed suicide in 46 BCE?

Revered today as a defender of the Roman Republic, Cato’s death followed months of psychological distress. For the hardworking senator, political upheaval fanned a substance use disorder. Cato was spending “whole nights drinking” before ending his life, biographer Plutarch relates.

What was he so upset about? For many Romans it was politics as usual. But to Cato and a number of others, something fundamental had shifted. Julius Caesar had bamboozled Rome’s low classes and quashed open government, they believed.

Cato’s political ally, Marcus Tullius Cicero was also gut-punched by 46 BCE, brought low enough to consider ending it all.

“I regard myself as doing wrong in the mere fact of remaining alive,” Cicero wrote the year Cato died. “Being inclined always to be active in some public task, I now have no scope — not merely for action — but even for thought.”

As we consider political distress in the age of Trump — documented in more than half of Americans in a 2017 American Psychological Association survey — Cato and Cicero’s experience resonates across the centuries. Digging deeper, we might ask why are some are hit hard, while others register little emotionally. Many lefties, for example, share a sense of frustration when a friend or acquaintance points out the bright side of current presidential policy.

For tens of millions of Americans, there is no silver lining. No comprehensive study charts Trump derangement syndrome, but at least one hints at its wide reach. A 2018 paper by San Francisco State University’s Melissa J. Hagan found 25 percent of college undergraduates impacted by the outcome of the 2016 election to the level of post-traumatic stress disorder. This implies millions of cases of depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and even increased rates of suicide linked to Trump and an American democracy on the ropes.

Writing in the journal History of Psychiatry, Australian scholar Kathleen Evans argues Cicero experienced a major depressive episode, in today’s vernacular. Cicero enjoyed a much happier outcome than Cato: by adhering to Stoic philosophy, a method much like our own cognitive behavioral therapy, Cicero passed from depression to his most productive period as philosopher and writer.

“No longer clinically depressed, he experienced persistent feelings of anger, sadness and regret,” Evans writes. “He lived quietly and discreetly under Caesar’s dictatorship, although he deeply disapproved of Caesar and felt unfairly and prematurely deprived of his career and public standing.”

In one letter from this time, Cicero says that it’s time to write “Republics,” or templates for good government, on paper, since we can no longer do so in the public square.

“I did not bear myself as one enraged at the man or at the times,” Cicero continued, in a vein that resonates with Trump-troubled Americans.

And, in one remarkable passage, Cicero jettisons his belief in Rome’s exceptional status. For Americans the paragraph pulsates with significance. Cicero suggests letting go of a belief that the American media, left and right, concur on: that American democracy is uniquely rational and resilient.

And yet, this belief is the very thing that Trump’s America may prove false. Continued faith in American exceptionalism generates cognitive dissonance. Letting go of the notion of exceptionalism, Cicero’s pivot suggests, may be the most effective remedy for our distress.

“For one thing in particular I had learned from Plato,” Cicero wrote as his mood improved. “That certain revolutions in government are to be expected. So that states are now under a monarchy, now under a democracy and now under a tyranny. When the last-named fate had befallen my country, and I had been debarred from my former activities, I began to cultivate anew these present studies that by their means… I might relieve my mind of its worries and at the same time serve my fellow-countrymen as best I could under the circumstances.”

Cicero’s endorsement of “mixed government” or “mixed constitution” inspired the American framers’ “checks and balances.” Readers of Plato and Cicero knew the ancient slur against democracy: that it devolves to mob rule. The first line of defense against this in the American republic would be education, John Adams said in 1787, a decade before becoming the second US president.

Adams seems readier to accept the danger demagogues pose to democracy than contemporary media executives, who leverage them for ratings.

“The people, in all nations, are naturally divided into two sorts, the gentlemen and the simplemen,” Adams wrote. “The common people, against the gentlemen, established a simple monarchy in Caesar at Rome. American common people are too enlightened, it is hoped, ever to fall into such a hypocritical snare.”

Thomas Jefferson, a skeptic on Plato and utopia, took a cool view of Cicero: when the righteous passions roused by Cicero start to cool, he wondered, “what was that government which the virtues of Cicero were so zealous to restore?”

We might ask a similar question.

“I do not say restore it, because they never had it,” Jefferson abruptly concluded.

The Rome of Caesar’s day had been roiled by coups, bloody street violence and partisan feuds for more than a century. By Caesar’s time, the corruption had grown worse. As history would show, Caesar’s removal didn’t reopen the door to republicanism and representative government.

We might more critically ask what today’s so-called resistance seeks. Does it expect to restore the republic? In Rome that never happened and idealistic Romans were left frustrated.

Looking back, that was Jefferson’s view too.

“Steeped in corruption, vice and venality, as the whole nation was, (and nobody had done more than Caesar to corrupt it), what could even Cicero, Cato, Brutus have done, had it been referred to them to establish a good government for their country?” he asked Adams in a letter.

As Caesar’s assassination on March 15, 44 BCE proved, removing one bad apple does not restore democracy. (The Roman Republic was no democracy in our sense, of course, but had democratic features, Oxford University’s Fergus Millar and other scholars argue.)

Caesar’s assassination marked the start of the Roman Republic’s end. The act unleashed civil war. Bounty hunters lopped off Cicero’s head a year later.

Violence churned until 27 BCE — the date where historians often place the Republic’s end. In that year, Octavian, the 36-year-old heir of Caesar, declared himself Augustus, literally “The Increaser.”

Both Stoic philosophy and cognitive behavioral therapy suggest a measure of acceptance is in order, given the situation’s imbalances. The stance is far from an embrace of the status quo and its demagogues, however. It still makes sense to vote, and pen op-eds, and march in rallies for social justice. The disproportionate influence of corporate power means our state is less democratic than it once was, though. It is logical — and healthy — to jettison a measure of faith in the system.

One more thing is clear: those with a small love for democracy feel little psychological pain today. In The New Yorker last year, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg declared his admiration for Caesar Augustus: “He established two hundred years of world peace,” Zuckerberg told writer Evan Osnos, a Harvard graduate and son of New York book publisher Peter L.W. Osnos.

“What are the trade-offs in that?” Zuckerberg asked.

Erik Skindrud is a writer and editor in Long Beach, CA.