Having reached a certain age, and having read my way here, I have begun to revisit some of the books I remember from years ago. Sometimes this happens because I have been cleaning a closet as part of the beginning of downsizing, but sometimes because life sends me a reminder.

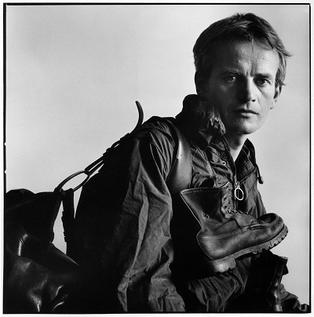

This past October Uluru/Ayers Rock, a Sacred Site of the Anangu outside Alice Springs in Australia, was closed to climbers and hikers. I have some understanding of what this must mean to the Anangu, but also to Australians who appreciate the richness of the original Australian cultures, only because I read The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin many years ago. I reread The Songlines recently, almost 30 years after my first read, and 30 years after Bruce Chatwin, self-identified nomad, travel writer, novelist, expert on art and antiquities, and so much more, died of AIDS at the age of 48. Now I have the joy of understanding what that book meant to me. I wrote this letter to Bruce Chatwin to share how The Songlines influenced my life, and as a reminder to keep cleaning closets.

¤

Dear Bruce,

I read The Songlines again last week. I first read it years ago, and, revisiting it made me think it might be nice for you to know some of the ways it influenced me. I’m hoping this account of some of the events of my life between 1989 and 2019 might be of interest as you were not able to be around during those years yourself.

In those days I traveled every week for work; tiring, but better (more nomadic) than being in an office every day. In the evenings I would often browse bookstores for a book that looked like it might be good. I can’t tell you how I made my choices except that I read the first page to see if the author could write well enough that the book might be satisfying. (I read on some website last week that you worked for Sotheby’s and rose through the ranks quickly in part by being able to recognize fakes, so you know what I mean.) Here’s what I noticed about your writing when I reread The Songlines.

I now see how your first page let me know I was in for a treat. I have been thinking more about the concepts of place and character for the last few weeks. Although I wasn’t focusing on these as concepts at my first reading, I now see that your first page, even the first paragraph, is itself a masterpiece. It draws vivid pictures of place: “Alice Springs — a grid of scorching streets where men in long white socks were forever getting in and out of Land Rovers.” The rest of the page paints an equally vivid picture of the first character we meet: Arkady Volchak. We learn his age, his appearance, his manner of speaking, his lineage, his parent’s story, that his smile is gentle, his bones large, that he moves easily, his marital status, parental status, that he plays the harpsichord, likes to read, is not materialistic, and has a natural preference for solitude. But the most intriguing details about Arkady were the ones in the first sentence, before we even know his name: “I met a Russian who was mapping the sacred sites of the Aboriginals.” You do not waste words. Not every character is described that completely, but every description gives the reader a sense of what the character looks like and what they value. If I learned nothing else from your book, I hope I learned that.

The way you combined your travel stories, memories of your earlier life, and excerpts from your journals was jarring at first. Most of the books I read before or since consisted of one approach or another, but not all together. I’m not saying I didn’t like it, because though the architecture of the book feels a bit odd, I liked it enough to keep reading until I not only finished it but then read it again, more slowly. I reread a book when it grows on me enough during the first reading that I realize, somewhere in the middle, that I’m probably missing a lot, when I think that the content is rich enough that I will see more in it, and get more out of it, when I reread it. Which I did.

I enjoy your quirky characters and places. Quirky to me because I have lived a fairly conventional life, although a lot less conventional than some family members. I grew up in Wisconsin, spent seven years I would still rather forget in Kansas City, have lived in eight different cities in both Northern and Southern California, and have never been to Australia. Some relatives and friends consider me quirky because I left the Midwest and have had far more jobs than children. I also traveled throughout the US and the UK for work. I only tell you this because I hope that you can see I have also been a nomad, although on a small scale.

I loved that you gather information from so many sources and from so many disciplines. I tend to do the same things, and I have always seen relationships between different things. I didn’t comment much in classes because I often drew blank stares from people when I did — that look that says, “What does that have to do with this?” I now have a niece who is the same way. As you know, it is great to find a kindred spirit.

But I did not benefit just from your use of words or the way you wove insights from varied times and cultures into a complete picture. Your explanation of climate change as a motor of evolution, of isolating mechanisms, how a temporarily isolated species can evolve into a new species and “Sometimes, invigorated by its change, may re-colonise its former haunts and replace its predecessors,” neatly dispensed with the silly argument that “gaps in the fossil record” disprove evolution. I remember your images of humans, away from the protection of the group, who fell victim to big cats: bites to the back of the neck, and human carcasses dragged into caves. Those images brought me back with a click of recognition to the recurring nightmares I had as a preschooler: lions and tigers prowling around my bed, nightmares that began after my dad took me to the circus and I saw big cats for the first time, snarling at a man with a long whip. My personal primal learning. You write that every child “appears to have an innate inner picture of the ‘thing’ that might attack, so much so that any threatening thing, even if it is not the real ‘thing’, will trigger off a predictable sequence of behavior.” That sent me on a journey.

At the time of my first reading I had recently become a consultant and trainer working with professionals on their business presentations. Within the field, there was no good explanation for the almost universal anxiety of public speaking. When I read The Songlines I was looking for answers. I did a lot of research on this idea in the years that followed, used the text often in my consulting and coaching work, and came to appreciate it more and more over the years. The Songlines led me to the thinking and writing of the Sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, his work on the nature of phobias, and to the thinking and writing of many others in sociobiology and related fields. I hope you are smiling. I’m guessing you read Wilson’s pre-1989 work — much of it came out in the 1970s and early 80s. But I was half a generation behind you, and I found him because of The Songlines. You sent me on that search.

I found and explored the concept of primal learning. I was able to understand and share with clients how standing apart from a group, all eyes on you, triggered the fight, flight, or flee response. I knew and could explain what that response does to the body and how to manage and minimize it. This was real, practical, and valuable information for many.

Of all the things I learned from The Songlines, one still stands out because of the punch in the gut you gave me when I read it: “Visitors to a baby ward in hospital are often surprised by the silence. Yet if the mother really has abandoned her child, its only chance of survival is to shut its mouth.”

I gave birth to my only child, a girl, five years after you left us. Against the advice of others, (“Just shut the door and let her cry herself to sleep. She has to learn.”), she was with me almost all the time. She slept in my bed, not her crib, and she traveled in a sling, not a stroller, until she could do all her own walking. She is now almost the age I was when I read The Songlines for the first time and is walking through her life with confidence and an open mind.

Since I found The Songlines I have read much of your other work. I wish you had written more. The short bio in The Songlines just said you “died outside Nice, France, on January 17, 1989.” I assumed that “outside” meant in an accident on a road, which seemed comforting to me somehow. Last week I learned more of your story. I lived and worked in San Francisco during the second half of the 1980s, saw the devastation, and lost friends and coworkers. I now know better what you went through when leaving us, and it breaks my heart. But Bruce, you rocked my world and made it better.