The fall of 2018, to paraphrase Philip Roth, is the fall when a Supreme Court nominee’s memory is on everyone’s mind. Not just any memories, but the allegedly virginal, beer-soaked memories of white teenage boys named Brett and Tobin in 1982 suburban Maryland.

Surely even Roth wouldn’t have dared.

These memories, of course, are part of a larger conversation at the center of American politics. For the right, the allegations against Brett Kavanaugh have evoked a mixture of white male rage and severe nostalgia. The left’s project has been equally broad, if at times more procedural: If Kavanaugh did in fact commit this heinous act, then Congress has not just promoted a criminal, but propagated a message of male impunity to the entire nation in a moment of #MeToo.

Ultimately, not enough Congressional Republicans were swayed by their colleague’s concerns, and Kavanaugh was confirmed to the highest court in America with the same attributes that characterize the accusations against him: belligerent, brute force.

But this charged national debate brought something else to the fore that is so often buried, yet increasingly important, in the age of Trump’s tabloid destructiveness: the politics of memory and whose history is told.

In this light, we can properly survey the underlying preoccupation of America’s tumultuous few weeks: an adjudication of whether those who’ve been privileged to forget will continue to outweigh those who’ve long been carrying the burden to remember.

¤

There is a difference between that which one has forgotten, and that which one “never knew,” the classicist Daniel Mendelsohn reminds us. But the history that we think we know is not inherently unforgettable. It is the legacy of contingency. Those with the power to decide what will be remembered have always done so, while also enjoying the privilege to forget.[1]

One might, of course, still have been surprised that a nominee for the Supreme Court with decades of experience on the nation’s top courts and a resume littered with America’s most prestigious universities, would curiously abandon legal caution for young male nostalgia and broadside polemics. But the court’s credibility was no longer of concern to the slim majority holding court on the Senate Judiciary Committee — they’d made that trade days earlier when the vowed to vote him through the following day, be damned the accuser’s testimony.

By the time Kavanaugh revealed his true self — the “son, husband, and dad” yelling beer soliloquies and Clinton conspiracies — they were after something else entirely: a pariah of bygone days, a thermometer to gauge what men like them could still get away with in this corrective moment of #MeToo.

Indeed, we know this forgetting well. It runs rampant today, though it remains the prerogative only of a select few. It is the stuff that compresses 20 women accusers down to “several,” for example, and required that Dr. Ford not just be credible but “everything a victim is supposed to be,” as Jessica Bennett observed in the New York Times.

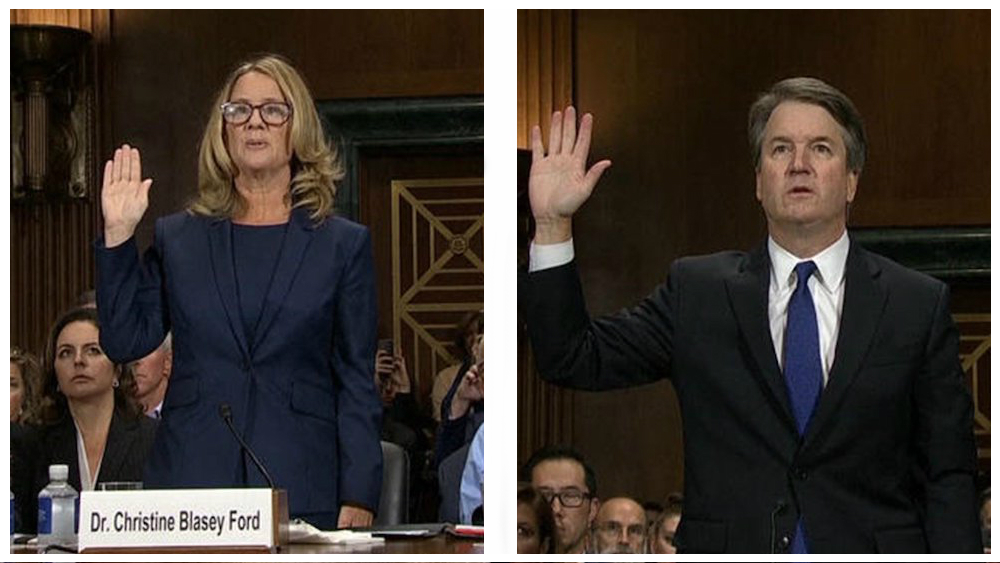

In this design, time took hold as the GOP’s central preoccupation. For Kavanaugh, it was tantamount to total innocence. For his accuser, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, it was immaterial; no amount of distance time provides could undo the trauma that had crystalized in her hippocampus that summer day in 1982.

Nowhere was this dynamic more starkly drawn than in their opening testimonies.

“Less than two weeks ago, Dr. Ford publicly accused me of committing wrongdoing at an event more than 36 years ago,” Kavanaugh began, red-faced and on the verge of tears.

“I am here today not because I want to be. I am terrified. I am here because I believe it is my civic duty to tell you what happened to me while Brett Kavanaugh and I were in high school,” said Dr. Ford.

Where Kavanaugh leaned on three words — “36 years ago” — as a refrain purposefully placed throughout his rage-filled tirade to remind us of the absurdity of it all, Ford never muttered them once. Where he sought to exonerate himself through time’s effortless erasure, she dealt in the now. Where his testimony was decidedly past tense (“I drank beer with friends, almost everyone did, sometimes I had too many beers, sometimes others did. I liked beer”), hers was present (“Mark was urging Brett on, although at times he told Brett to stop”). Where his testimony was often indignant — how dare I be forced to remember details from my past?? — hers was burdened by the weight of her personal history.

Compare Kavanaugh’s melodrama to Ford’s tempered precision.

Kavanaugh:

When I was in town, I spent much of my time working, working out, lifting weights, or hanging out having some beers with friends as we talked about life and football and school and girls, some have noticed that I didn’t have church on Sundays on my calendars, I also didn’t list brushing my teeth, and for me going to church on Sundays was like brushing my teeth, automatic, like it still is.

Ford:

One evening that summer, after a day of swimming at the club, I attended a small gathering at a house in the Chevy Chase/Bethesda area. There were four boys I remember being there: Brett Kavanaugh, Mark Judge, P.J. Smyth, and one other boy whose name I cannot recall.

His was the story that’s always been told, hers the “unreturnable covered memory,” to borrow from novelist Tommy Orange, that we’ve long asked victims to suffer with in silence.

In this space, Kavanaugh sought to shed his 17-year-old self, where Ford could not. “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter,” she told the Senate Committee of the night Kavanaugh and his friend Mark Judge allegedly assaulted her.[2]

¤

It is little surprise Kavanaugh’s defenders on the right meditated so heavily on the power of time passed. Nor is it surprising it was the first thing McConnell uttered after getting his way.

On Saturday, after voting in Kavanaugh by a slim majority, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tried to wave away the last few weeks by offering the Republican equivalent of a Hare Krishna chant: “These things blow over,” McConnell said on the senate floor.

Time, after all, is the reliable drug that transformed a one-time alleged war criminal into a soft and cuddly meme.

But time was also an obsession of the Democrats and the larger movement coalescing on the left. Those forces also seemed aware, beneath the immediate political project at hand, of the historical stakes at play.

“The sand is running through Kavanaugh’s hourglass,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse offered menacingly in his closing remarks on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The senator was speaking specifically of political cover-ups, but his warning could apply to the larger institutions that for so long have privileged men like Kavanaugh the luxury to forget past indiscretions so long as the other party stays silent.

Yet, across the country, that is changing, as Ford calmly exhibited. Now, those long forgotten by time’s duller instruments, are speaking up.

Now, they have an audience.

“Many of the women shouting now are women who have not previously yelled publicly before, many of them white middle-class women newly awakened to political fury and protest,” writes Rebecca Traister. “Part of the process of becoming mad must be recognizing that they are not the first to be furious, and that there is much to learn from the stories and histories of the livid women — many of them not white or middle class — who have never had reason not to be mad.”

Time, by sheer arithmetic, is on their side, and Mitch McConnell knows it. One assumes Brett Kavanaugh does too.

“You sowed the wind, for decades to come, I fear that the whole country will reap the whirlwind,” Kavanaugh shouted hours after Ford addressed the senate.

¤

It is telling that Kavanaugh ended his tirade the same way he began it, by relying on the passage of time to serve as the ultimate symbol of his incredulity. It is an unmistakable emblem of entitlement.

“[I]f the mere allegation, the mere assertion of an allegation, a refuted allegation from 36 years ago is enough to destroy a person’s life and career, we will have abandoned the basic principles of fairness and due process that define our legal system and our country,” the judge said.

Notice the repeated use of “mere” carefully placed to undercut each mention of the allegation before arriving on the savior of this sentence, the crux of the argument — the 36 years.

Kavanaugh returned again to the passage of time when he wrote his seemingly inevitable mea culpa in the Wall Street Journal one day before key Senators announced their intention to back him. This time it wasn’t 36 years, just a week — memory works in dog years for men of Kavanaugh’s privilege apparently — to protect his story.

One week on, Kavanaugh’s deranged toddler-esque performance before the Senate Judiciary Committee was now simply “too emotional at times.”

“I know that my tone was sharp, and I said a few things I should not have said. I hope everyone can understand that I was there as a son, husband and dad. I testified with five people foremost in my mind: my mom, my dad, my wife, and most of all my daughters,” he continued.

But Kavanaugh’s performance, and the indignation he displayed when confronted with someone else’s memories, will not be forgotten anytime soon.

If only because nothing since Trump’s elevation to the presidency has so nakedly exposed the institutional right’s utmost preoccupation. And it put to lie once and for all — one would hope — the delusional idea that there is such a thing as Republicans who resist Trump.

In this regard, Kavanaugh’s testimony was undoubtedly unforgettable. It provided the clearest blueprint to date for just how far this institution will go to maintain a system that’s served them so well.

As cynical as it is, this blueprint may continue serve them well, as it did in securing Kavanaugh’s confirmation. But it’s an unlikely harbinger of greater victories in the long run for the GOP or men of Kavanaugh’s privilege — just the body’s final evacuation before rigor mortis sets in.

[1] History provides endless antecedents, of course. China’s never-ending effort to purge Tiananmen Square from the public record. The American Southerners who would like us to believe that their racist statuary dates to the antebellum period, when, more often than not, it is an artifact of Jim Crow. The Polish government’s infantile attempt to criminalize any mention of “Polish death camps.” By the time Germany was preparing for the Second World War, it had convinced itself that the first one had never been lost.

[2] If these processions had one defining feature, it’s how religiously they adhered to this logic. It is even evinced in the science of these memories.

“In a situation where a woman fears being raped by a man, her memories might be shaped by that fear into a recollection that overestimates the threat, whereas the man might consider it “just playing around” and forget it, said David Rubin, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.” (Malcolm Ritter, Associated Press).

Kavanaugh’s brain literally has the chemical infrastructure that privileges his forgetting, while Ford’s is mechanized to produce the opposite effect.