How do you solve a problem like the avant-garde? That is a question that John Baldessari has been asking in one form or another for more than five decades. Since July 24th 1970, when, in an inspired moment of getting-over-it, Baldessari and his students at the University of California at San Diego burned the last-gasp gestural paintings that he had made between 1953 and 1966, he has been exploring different ways of pushing the most compelling elements of advanced visual art out of the ever-narrowing confines of academic modernism and into the rich and unpredictable space of actual looking.

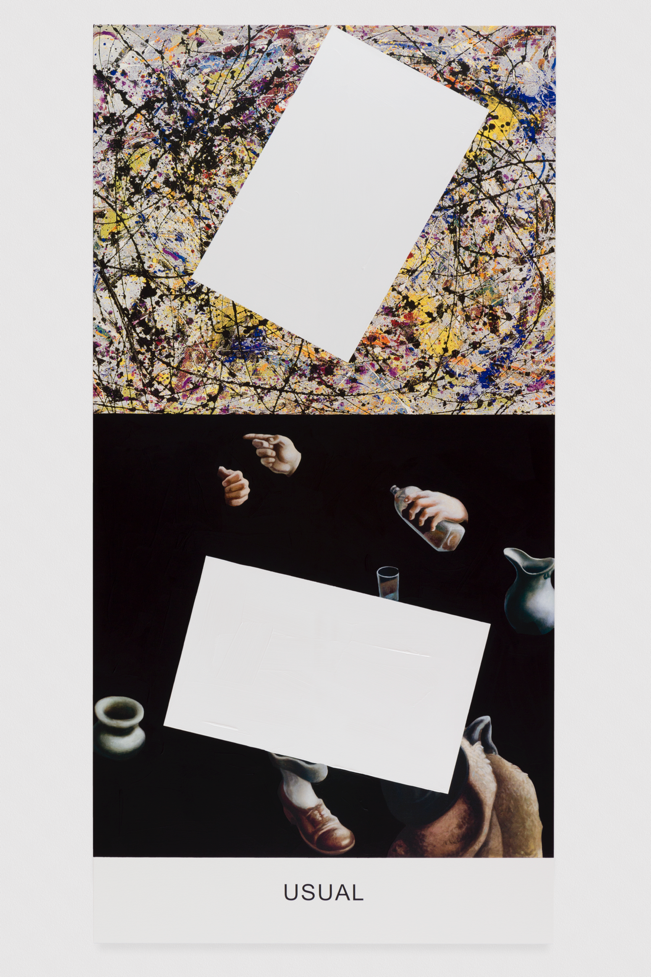

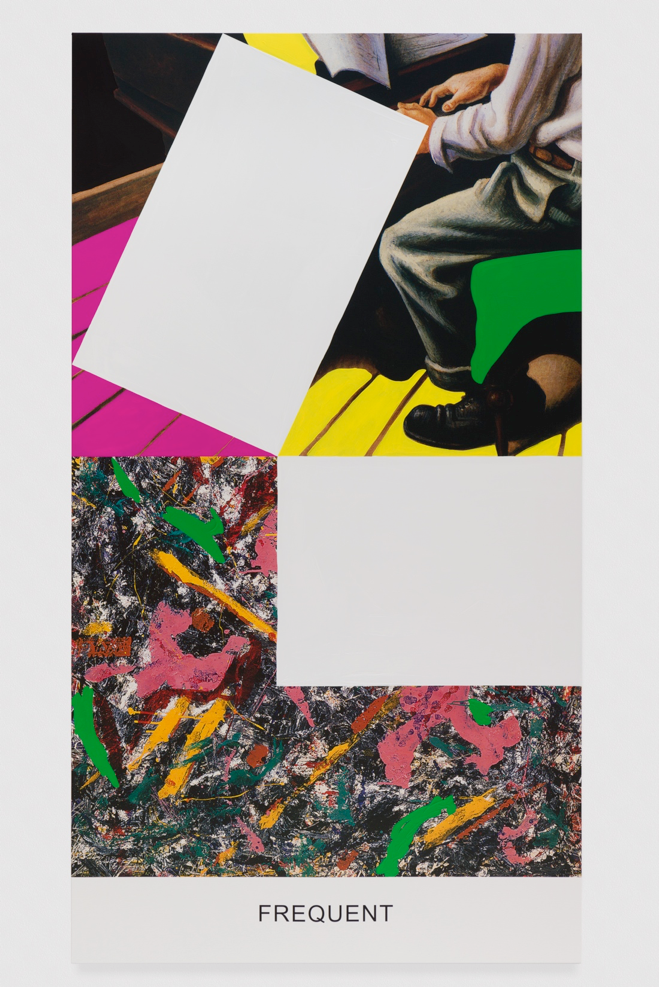

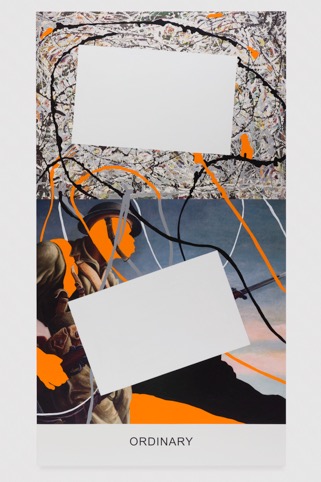

In his Pollock/Benton series, which he completed this year and which was recently on view at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, Baldessari offered the most compelling solution to the avant-garde problem yet: instead of working for it, make it work for you. Tall, slim canvases measuring around eight feet by four, the works are bisected horizontally at the center and reproduced in pixelated inkjet details of paintings by the American masters Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock on their top and bottom halves. To these, Baldessari has added his signature fields of acrylic over-paint, in some cases broad swathes of matte black and in other cases shaped passages of saturated blues, yellows, oranges, and greens, as well as large white rectangles, also in acrylic, suspended at varying angles more or less in the middle of each reproduction. Finally, he has anchored each work with an everyday word like “FAMILIAR,” “COMMON,” or “ROUTINE” painted in black block lettering on a narrow white band bellow. To walk through the gallery’s two-and-a-quarter rooms is to get down to what suddenly seems like the long-overdue work of taking the avant-garde back. Moving from one work to the next, following Baldessari as he uses over-painting to point out and comment on formal associations between this Pollock and that Benton and then building on those associations in the white interruptions provided, you can feel the thin skill of citation drop away and be replaced by the thick skill of attention.

Baldessari’s complex relationship to the avant-garde runs deep. Born in 1931 five miles south of San Diego in National City, California, which at that point was a dust-and-diner town with a population of around 10,000 residents, many of whom had been hit particularly hard by the Depression, Baldessari had his culture delivered to him by mail. Subscribing to whatever art magazines he could find, he began a years-long project of self-education, pouring over print reproductions as he attempted to work out what art might be. One gets the impression from this abridged and anecdotal history, which Baldessari repeats often in interviews and artist statements, that having built up his visual acuity in this way, flipping from dog-eared page to dog-eared page, he entered the art world in 1955 after brief stints studying painting at San Diego State College and art history and criticism at Berkeley expecting to find others who had been similarly exploring the broad terrain of avant-garde viewing and was shocked when he instead ran into the brick wall of avant-garde theory.

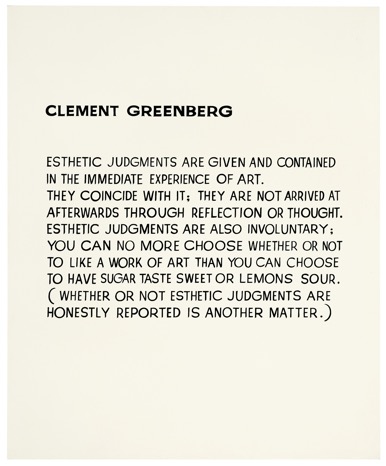

That brick wall had a name: Clement Greenberg. Having started out as a spirited young Marxist critic writing for Partisan Review in the mid 1930s, Greenberg had by the early 1950s become something of an albatross around the artist’s neck. His theory of medium specificity, which posited that all artworks amounted to a reckoning with the materials out of which they were produced, had limited the terms of art critical conversation, replacing an expanding avant-garde that was oriented toward art’s many beginnings with a contracting avant-garde that was oriented toward art’s one end. Though Baldessari signed on to the Greenbergian project for a time, making appropriately brushy paintings in the late Abstract Expressionist mode, he soon balked at the contraction. In 1966 he stopped making those paintings, most of which he would burn on that afternoon in July, and started making instead medium-defying text paintings, one of which addressed Greenberg by name. That work, titled appropriately enough Clement Greenberg, picked up where the earlier self-education had left off. Returning to the do-it-yourself pursuit of visual acuity that Baldessari had gotten underway as a bootstrapping amateur in National City, the painting mounted a commonsense defense of the expansiveness of viewing against the narrowness of theory that Baldessari would continue to develop throughout his career. “Esthetic judgments are given and contained in the immediate experience of art,” the painting wryly explained. “They coincide with it; they are not arrived at afterwards through reflection or thought. You can no more choose whether or not to like a work of art than you can choose to have sugar taste sweet or lemons sour. (Whether or not esthetic judgments are honestly reported is another matter).”

In many respects, it is Greenberg and his heirs, including the theory-prone believers-turned-apostates who have shaped discussion more recently, that we are looking past in Pollock/Benton. After all, Benton, despite being Pollock’s instructor in the Mural Division of the Works Progress Administration, represents the path-not-taken in Greenberg’s art history, which as we all know, associated Pollock’s drip-and-splatter technique with a logically determined march toward painterly abstraction that had its source in French Impressionist origins of the modern era rather than in a young artist’s less predictable interest in the churning motifs of his mentor and friend. While scholars have long pointed out that interest in essays and monographs, noting, for example, the striking similarities between the curvilinear preparatory drawings that lined Benton’s studio during the WPA years and Pollock’s own arching calligraphic skeins, Baldessari puts those similarities on display in such a way that the sheer act of noticing, the sheer act of picking up and riffing on a form by which a visual tradition passes haphazardly from one artist to the next, becomes something in which we as viewers are urged to take part.

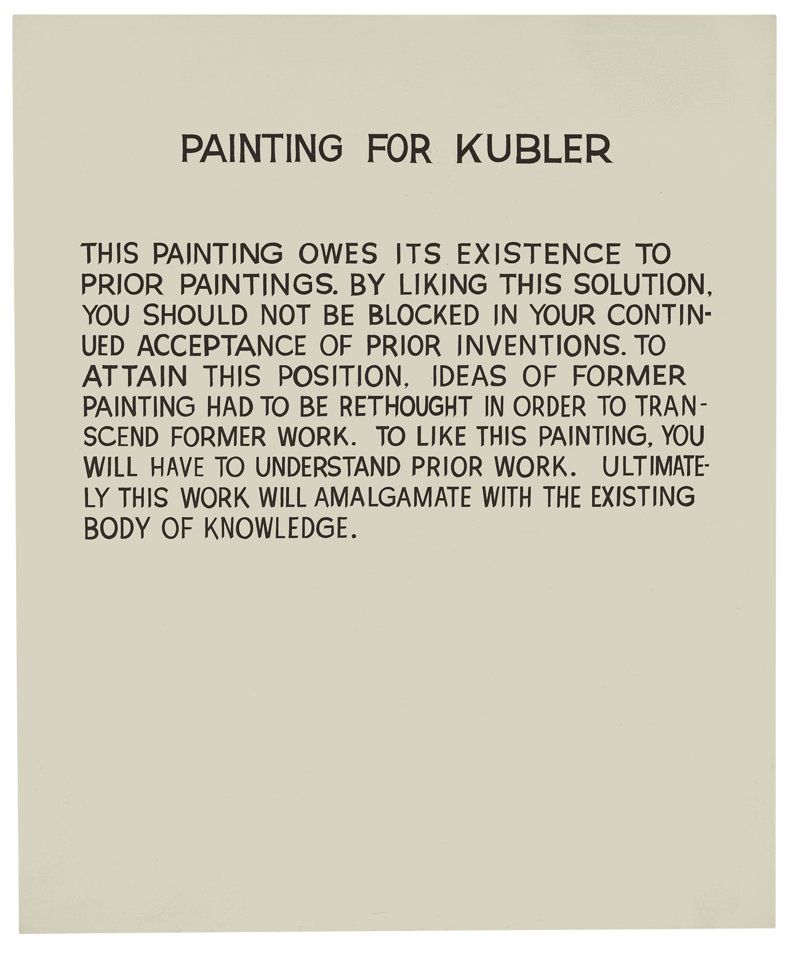

Foregrounding that act of noticing is one way that Baldessari encourages us to look past Greenberg. Another is by short-circuiting the sequentialist this-leads-to-that structure on which his art history, like so much academic modernism, depends. In another text painting from the late 1960’s, Baldessari pointed out how restrictive that structure could be. Dedicated to George Kubler, the historian of South American art whose influential treatise The Shape of Time was published in 1962, one year after Greenberg’s legacy-making collection Art and Culture, that painting upended modernist sequentialism and provided some practical relief to those who chaffed at its constraints. “This painting owes its existence to prior paintings,” it matter-of-factly declared. Using the more flexible rhetoric of real-time problem solving that made Kubler so attractive to artists of Baldessari’s generation, the painting continued, “By liking this solution, you should not be blocked in your continued acceptance of prior inventions. To attain this position, ideas of former painting had to be rethought in order to transcend former work. To like this painting, you will have to understand prior work. Ultimately this work will amalgamate with the existing body of knowledge.”

In Pollock/Benton, sequentialism is upended by the reversibility that is stated in the series’ title, which places Pollock on the near rather than the far side of that pivoting forward slash, as well as by the reversibility that is performed in each of the works, which place Pollock and then Benton alternatingly on the top and bottom of the canvases’ porous center-line, privileging matters of perception over matters of precedent.

Arguably the most visceral way that Baldessari encourages us to look past Greenberg, however, is simply by insisting that we anchor our viewing in the “immediate experience of art” that Greenberg, in his enthusiasm for theorizing, had often overlooked. When seen up close and in person, one is struck by how fresh and damp the acrylic seems, as if it had been applied mere moments before you walked in. The passages of over-paint vary in their opacity, and in some cases look like quick first coats that have been left casually to dry. Many of them retain their bristled ridges and stand out against the flattened surface of the inkjet reproductions underneath. These touches, slight though the are, together give the impression that those reproductions were seen in a particular way at a particular time by a particular person, an impression that Baldessari doubles-down on in his choice of palette in works like Pollock/Benton: Frequent where he shifts away from his earlier preference for more to-the-point primary reds, yellows and blues in favor of more idiosyncratic shades of fuscia, cobalt, and ochre.

The result is a bracing back-to-basics course in our own ability as viewers. Part of the thrill of these new paintings is their reminding us just much mileage we can get out of the Pollocks and Bentons. These are presented less as specific titled-and-dated paintings than as part of the more generic background repertoire that we as American gallery-goers bring to the table. The application of over-painting is meant to remind us of that ability by showing how much of our repertoires go unused. In a 2005 conversation with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Baldessari described how the addition of over-paint was meant to provoke a sense of “anxiety” at “not knowing what has been omitted,” a feeling that he elsewhere described as giving viewers “another chance to understand.” Although he made that remark while discussing his earlier practice of blocking-out of elements of photographs that would provide important narrative information like faces and settings, the technique produces similar results in the Pollock/Benton series. By selectively covering-up passages in the reproductions, the over-paint de-familiarizes the all-too-familiar works, allowing us to re-discover aspects in them that we, for all our knowingness, might have missed. A similar function is served by the addition of the white rectangles, which Baldessari first began experimenting with in works from his Violent Space series, such as the collage Violent Space: Two Stares Making a Point But Blocked by a Plane (For Malevich) from 1976. There, a black-and-white movie still of two thuggish men in an alleyway is partially covered by a rectangular piece of white paper, strategically placed so as to obscure the object of their gaze. Discussing that work, Baldessari described how the addition of the piece of paper was meant to “oppose with formal means” the otherwise obvious narrative implication of the photograph, causing a collision of elements that would result in what he called a “synthesis that would have a power beyond its parts.” In the Pollock/Benton series, the painted rectangles act in much the same way. By obscuring parts of each of the reproductions in a given work, they override stale distinctions between the figurative and the abstract that have informed so many end-of-painting scenarios, providing spaces in which we are able to come up with our own synthetic third terms.

The words at the bottom of each of the works also contribute to this back-to-basics approach. Not only do they speak to the kind of casual, everyday facility in viewing that Baldessari is trying to recover, recalling a pragmatic cast of mind that has been largely sidelined by both the Greenbergian and post-Greenbergian schools, they also serve as synonyms for an absent word that remains unstated. In that sense they offer one more way to avoid the bottlenecking of thought that too much theory can cause. Variations rather than refutations, they cast a wide net of meaning and deal in inflections and tones rather than in formulas and slogans.

The back-to-basics approach is not that of the naïf, however. For all his bridling at Greenberg and the rest, Baldessari is neither anti-theory nor anti-avant-garde. His commitment to the productive potential of “anxiety” and his dedicatory nods to Malevich, not to mention his opting for hand-on-the-shoulder in-jokes rather than outright denunciations, make that much clear. He would, as far as I can tell, just rather that they be handled with a little more inventiveness and wit, which is to say a little more confidence, than is typically the case. Perhaps that is why the series draws so heavily on the pedagogic methods that Baldessari has been developing as a teacher for years. For many viewers the format of the works will, by combining paired images, notational color, and captions, call up recollections of the slide lectures, survey textbooks, and exam notes, with which they first began the disordered, rough-and-ready process of tutoring their eyes and learning to see.

That is a lesson that is worth learning again, especially now. There is little doubt that Baldessari made the Pollock/Benton series with nationalism in mind. Not only does the subject matter root even the most sophisticated visual exercises that we viewers perform in something like a vernacular tradition, a rooting that is in keeping with the democratic spirit that underwrites so much of Baldessari’s work, the Bentons in particular are taken from the antifascist Year of Peril series that he made in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the seventy-fifth anniversary of which just passed. Whatever Americanist accent that reference might have otherwise had will now, needless to say, fall somewhat differently. Opening two days after the election of Donald Trump and closing less than a month before his expected inauguration, the nationalist undertone of the series gives it what we can only assume is an unintended charge. That is not to say that the series is ill timed. On the contrary the model of avant-garde viewing that it lays out, a model that is at once more nimble and more sure-footed than the baroque alternatives that many of us are used to, strikes me as well suited to the situation we now find ourselves in. In its practicality and resourcefulness, its workaday commitment to the development of skill, the series seems like it has a good deal to offer us as we set about solving what are likely to be the very real problems ahead.