Phil: KRISTEN SCHAAL as LOUISE in BOB’S BURGERS

SO, HERE BEGINS our round-robin discussion of the year in television. Today we do favorite performances. I shall begin with a grandiose statement undercut with a qualification: This year was a phenomenally good year, I think the think-piece generators of the world have agreed, for women on TV. That’s been said every year for the past little while, but it seems especially true this year if only because Orange is the New Black unceremoniously dumped about a dozen different chewy, complicated, gorgeous parts for a breathtakingly diverse group of women right on to our Netflix queues this year. The sexism of the TV biz has been well-remarked upon, and I certainly understand that the more times critterati declare a year to be the “YEAR OF THE WOMAN,” the more the general public is going to be convinced that these endemic problems are solved. But there has to be a way of acknowledging how fabulous it is that the criminally under-rewarded Elisabeth Moss was able to play TWO of the top five best roles on television this year on two different programs and Tatiana Maslany was able to play three times that many on the same show without it seeming like a false victory lap. Rather than declaring anything any more profound, let me just say that, in trying to figure out a favorite performance of the year, the only actors that come to mind for me are women. And that has not always been true.

All that said, the performance I want to single out is neither new nor likely to be included in any inspirational listing of how ladies got their grooves back in 2013. The performance that’s stuck with me most this year has been Kristen Schaal’s voice work as the criminally-insane youngest daughter Louise on Fox’s wonderful Bob’s Burgers. I came late to this cartoon, in part because I have a genuine distrust of Fox’s “Animation Domination” Sundays based primarily on the harrowing depression I feel whenever I encounter a new Simpsons episode and the gag-reflex that kicks in whenever Seth MacFarlane puts his slimy mitts on anything at all. But Jane pestered me into catching up on Bob’s Burgers this year, and I found what has been obvious to fans of the show for years: it’s very simply one of the best family comedies on TV.

I could go on with all of the convert’s zeal that I now possess about how it’s just as good as Parks and Rec or how remarkable it is for a television show as acerbic as this one to be as interested as it is in the concept and practice of love, but that’s for another time. Right now, Kristen Schaal. Schaal’s stand-up has always been uncomfortable to me. Partly because it’s supposed to be uncomfortable in a Steve Martin, Andy Kaufman sort of way, but partly also because sometimes the big conceptual jokes don’t stick. Schaal’s Louise, however, has none of the irony of Schaal’s stand-up act. She is high-pitched, unabashed, unkempt, contained only by the pink bunny ears she wears on her head. The easiest comparison is Charlie Day’s performance on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, but where that performance is loud out of desperation and frustration, Louise is loud out of a psychotic lust for life. The way that Schaal is able to subtly modulate a mode of address that can mostly be described as “screaming-at-the-top-of-her-voice” is nothing less than stunning.

And this season, Schaal modulated that voice to a totally new place. Bob’s Burgers is amazing on the topic of adolescent sexuality. From eldest daughter Tina’s obsession with sexy dancing zombie butts to middle-child Gene’s confused interest in private parts, the show is terribly good and terribly innocent about staking out how weird sex seems to the minds of children. Louise, despite having perhaps the most fully-formed psyche of any of the kids, however, has largely maintained a critical distance from puberty until this season. In the third season episode “Boyz 4 Now,” Louise accompanies Tina to the concert of a One Direction-style boy band called Boyz 4 Now. Initially disdainful of this errand — ”Don’t waste your screaming on a stupid boy band. Screaming should be for rollercoasters, or axe murderers, or dad’s morning breath.” — Louise falls immediately, inexplicably in love with one of the members of the group.

Schaal’s handling of the anger and betrayal Louise feels as she finds herself attracting to a boy for the first time is actually quite moving. But, more than that, it opens up a new register of this top-register performance as Louise’s murderous rage turns to murderous romance. Schaal does Louise on a high-wire, and hearing her fall off this season was just as joyfully disturbed and disturbing as you might imagine.

¤

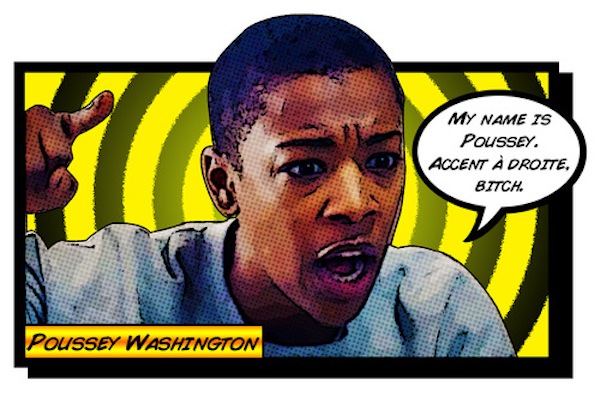

Lili: SAMIRA WILEY as POUSSEY WASHINGTON in ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK

Phil, I’m thinking of the joyfully disturbed women too. There’s been a lot of ambitious stuff on TV this year, and for those of us longing for better parts for women, it’s been a treat to watch some of the top-shelf stuff on offer: Top of the Lake, House of Cards, Mad Men, Masters of Sex, The Good Wife, etc., and yet there’s something a little decadent, a little fudge-like, about the experience. The sheer luxury of the thing, the abundance of top people and quotable lines, brings out the contrarian in me. What I really want, when I’m in a position to choose a jewel from the lot, is something just a bit plain, a perfect loaf of bread.

Orange is the New Black brims with talented actors. I think it’s the best thing that’s happened this year. But juggling that giant, magnificent cast sometimes required (or at any rate resulted in) a kind of affective shorthand, which in turn produced some slightly embarrassing over-expository preachy moments. This is especially true of the show’s much-discussed practice of expanding outward to outfit each character with a past. The results are spectacularly uneven. If you’ll forgive a swirl (of metaphors): Kate Mulgrew’s Red gets the most compelling back story, I think — let’s call it high couture. Miss Claudette’s is a touch melodramatic but whew is it memorable (bravo, Michelle Hurst). It’s to Dascha Polanco’s credit that her Daya Diaz brings a deeply compelling idiosyncratic sensibility to what might otherwise feel like a rehearsal of minority underworld tropes. Madeline Brewer channels her character Tricia Miller’s fragility, dimness, and psychology of debt in a totally heartbreaking performance — she does her material justice. Other actors are given less history to work with: Alex Vause’s past feels like a knockoff, and Natasha Lyonne’s Nicky and Vicky Jeudy’s Janae Watson’s stories are definitely (and disappointingly) off the rack. As for Taryn Manning, we can admire her total triumph at selling it while noting that Pennsatucky deserved better than to be both a meth-addicted serial aborter and a messianic uber-Christian murder-angel.

In any event, when I tried to think of the performance that stuck with me this year, as much comedically as dramatically, it belongs to a secondary character with limited lines, a second-stringer whose back story we don’t yet know: I’m talking, of course, about Samira Wiley’s Poussey Washington.

She was given less to work with than most of the characters on OITNB, and yet every scene she’s in glows. She’s luminous. Bird-like. Her presence is consistently irreverent and hilarious and — in the Christmas episode finale — an unexpected and sublime foil to Piper and Pennsatucky. Her performance of white people politics is one of the comedy highlights of the season; Wiley and Danielle Brooks have wild chemistry of a sort we rarely see on the small screen. (Somebody please give them their own show.) And if many people have written (rightly) about how moving they found Taystee and Poussey’s reunion in the library after Taystee returns from prison, Taystee’s disquisition on minimum wage in that scene feels (in my opinion) a tad didactic. It jars oddly with Poussey’s reflection on her mother’s death. My favorite scene between the two is this one, right after Taystee gets dominion over the TV:

“My name is Poussey! Accent à droite, bitch. It’s French. Poussey’s a place in France where my daddy served and kings were born and shit. Fuck you named after?”

I love this scene because of its erupting layers: it shows the stakes of the TV and the passion it inspires, it shows what Poussey unironically loves (Ina Garten!), and the way the WAC can genuinely affect the inmates despite universal protestations to the contrary. We sort of learn where both Taystee and Poussey’s names came from, killing whatever vaginal jokes might haunt the friendship. Best of all, we learn how the closest friends on the show fight — which, though I’d be lying if I said I had fully formed expectations, isn’t at all how I’d have predicted they’d choose their weapons.

You could say I’m grading “best performance” on a curve, thinking about who did the most with the least material. I can’t say enough about Wiley’s range. Her expression when Poussey watches Taystee leaving, the wry energy with which she wishes Black Cindy a “joyous Kwanzaa!”, her wit and intelligence generally contrasted with her consternation when she tries to scare the kid in the wheelchair — every scene this woman is in sparkles.

¤

AHP: HAYDEN PANETTIERE as JULIETTE BARNES in NASHVILLE

A classmate of mine once asked our professor how she would know how to approach and analyze her object of study. His advice: the broccoli will usually tell you how it wants to be cooked. In other words, the subject matter will suggest how to approach it.

That’s how I feel about Nashville: the subject matter (country music, Nashville politics, sprawling family drama, complicated teenage girls, figuring out how to cope after divorce) told showrunner Callie Khouri how to cook it, and with the encouragement of ABC, she’s allowed the pot to boil over. Repeatedly. But that’s far from a criticism. Even if Khouri’s own husband T. Bone Burnett resigned from his role as music director in protest over the direction of the show, I revel in its embrace of its soapy roots. Last season it was trying to straddle the line between primetime soap and quasi-quality drama; now it’s all melodrama, all the time, and it’s (almost always) delicious.

Plus I’ll forgive any number of boring scenes of over-acting Powers Booth so long as I get to see my girl Hayden Panettiere steal every scene as Juliette Barnes. When Panettiere was on Heroes, I found her flat, uninteresting, and unworthy of the hype — words that also describe my general feelings towards Heroes. When she and Connie Britton were cast as rivals on Nashville, my allegiance was all for Mrs. Coach.

The narrative restricts Britton to a slightly more sequined version of her Mrs. Coach, but Barnes is something I’ve never seen on television: a tremendously powerful woman in constant battle with her history, but a history defined by class and its ramifications, not men. Like Britton’s Rayna James, Barnes has a lost love that defines her life — but that lost love is her addict mother, not a boyfriend. That a female character could be almost wholly motivated by the enduring memory of her class position — rather than the men in her life — is revelatory.

Granted, Nashville’s narrative keeps trying to throw potential love interests Juliette’s way. But there’s something about Juliette (and Panettiere’s performance of her) that makes it impossible for any of those boys to stick. It’s not as if she’s some ball-busting ice queen — or, more precisely, it’s not as if she’s just some ball-busting ice queen. Juliette busts balls, but every decision she makes is working towards escaping the specter of a little, dirt poor girl, living in a trailer with a mom who couldn’t even be relied upon to feed her. That might sound hackneyed, but the way the show (and Panetierre) work to complicate the interplay between the exploitation of that past (to promote her image and albums) and the actual experience of it is anything but.

Once in self-preservation mode, always in self-preservation mode. Juliette’s eviscerated inside, but the only way to stay on the path that took her out of the trailer park is to be perfect on the outside.

With a less talented actress, that duality could seem schizophrenic. But Panettiere nails it: in part because she’s so good at showing the slight seams in celebrity production (her dazzlingly fake smile; the way she turns it on for men in power), but also because she’s an amazingly talented music performer. It’s not just her voice (which is great) or her songs (which are perfect) but the delivery: watch her on stage and you understand everything. Or, more precisely, you understand just how authentically complicated her life is: she’s tasked with embodying the American Dream (and postfeminism!) every day and that shit is EXHAUSTING and terrifying and never as gratifying as she wants or needs it to be. In classic melodrama, the melos (song) expressed the ineffable emotion the narrative itself could not — it’s where you see sexual desire, anguish, regret, and power. The lyrics to Barnes’s songs do that, but Panetierre’s performance does it even better.

¤

Jane: ELISABETH MOSS as ROBIN GRIFFITH on TOP OF THE LAKE

I’m so glad we’re calling this “favorite” rather than “best,” especially since the latter adjective is having its moment now that we’ve reach the End Of Season. While I didn’t actually watch much new television past August, the consensus stays: women really brought it this year. And television gave them the space to bring it. Even off cable and network television, our beloved Netflix really gave their female leads room to shine in both House of Cards and Orange Is The New Black.

But when trying to parse through my favorite performances, I keep finding the female performances that stayed with me most one more remove from America’s already diversifying (relatively speaking!) television scene: import television. Tatiana Maslany of Orphan Black (Canada), Sidse Knudsen of Borgen (Danish), Elisabeth Moss of Top of the Lake (Australia). All three shows are related to the crime drama, but explore the genre in compelling and surprising ways, making me wonder if perhaps these overworked women should all take a vay-cay in some shipping container with the homebound Carrie Mathison.

My pick of Elisabeth Moss’s performance as the verrrry complicated detective Robin Griffith is probably overdetermined. I mean, Jane Campion directed Top of the Lake. But unlike Maslany and Knudsen, Moss’s character contained this almost aggressive nervousness and anxiety that not only added to her role as uncertain detective in an increasingly odd case, but spoke, I’m guessing, to many viewers on a more personal level. Like Carrie in the first season of Homeland, we’re constantly on the verge of wondering what Griffith might not know about herself, and yet this awareness only draws us closer to her. While Robin is out trying to protect the women and children of Laketop, I grew increasingly protective of her. And, no spoilers, but rightly so.

Moss’s performance held what a lot of boundary-pushing dramas lose (as if by necessity) and that is nuance. But, like, a rigorous amount of nuance. Is Moss a method actress? At moments, her little breaths, gasps, pauses, and cringes made me wonder how much distance lay — in that moment — between Moss and Robin. I couldn’t believe this was the same woman who played Peggy Olson (who, if you return to season one of Mad Men, is almost unrecognizable from the ad woman we know now at the end of season six; listen to how her voice pitches up and how her phrasing melts at the end of her sentences, like she’s trying at once to disappear and integrate into the office environment). Moss gives performances that come across both intensely studied and breathlessly in the moment.

That Top of the Lake was a miniseries might be part of why Moss’s incredibly flawed and faltering character is so clearly crystallized. It’s hard to convey that level of ambiguity visually, and Robin Griffith’s wavering or paranoid “aura” comes across almost novelistically. It gets expressed through an accretion of (very telling!) gestures and shifts in voice and tone. Voice and tone are also, incidentally, huge words when it comes to the study of narratology.

I would almost describe Moss’s performance as descriptive. Watching Top of the Lake is like watching yourself watch Robin watch herself (or try not to watch herself) — the strange accumulation and crossing of perspectives is fascinating, and, again, incredibly novelistic. Moss is acting out a plot, Robin is caught in a plot she doesn’t entirely understand, but my favorite parts of Top of the Lake were incidental to plot. They were descriptive, occurring when Robin was, sometimes inadvertently, exposing something about her character. Of course, character is never extraneous to plot or the official task at hand — especially when you’re supposed to be an objective detective and Strong Woman — and Moss really got at something in her occupation of cohesive uncertainty.

The background noise and mood of Top of the Lake is astonishing, and, being a miniseries, we’re able to watch it over and over again and simply sink into Moss’s performance. It’s unnervingly good.

¤