By Paul French

Anne Witchard’s England’s Yellow Peril: Sinophobia and the Great War is the final volume in the Penguin China World War One series of short books that have highlighted the various aspects of China’s involvement in the Great War (previously discussed at this blog by Maura Elizabeth Cunningham). England’s Yellow Peril builds on Witchard’s previous work, looking closely at British perceptions of China and the Chinese through literature and the arts in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. In England’s Yellow Peril she looks at how the outbreak of war accentuated and intensified many feelings of English racial dominance, Empire, and notions of the Yellow Peril that had arisen before the conflict. She concentrates on London’s old Chinatown of Limehouse in the East End, where swirling tales of opium smoking, gambling, and interracial romance had became synonymous with the presence of the Chinese.

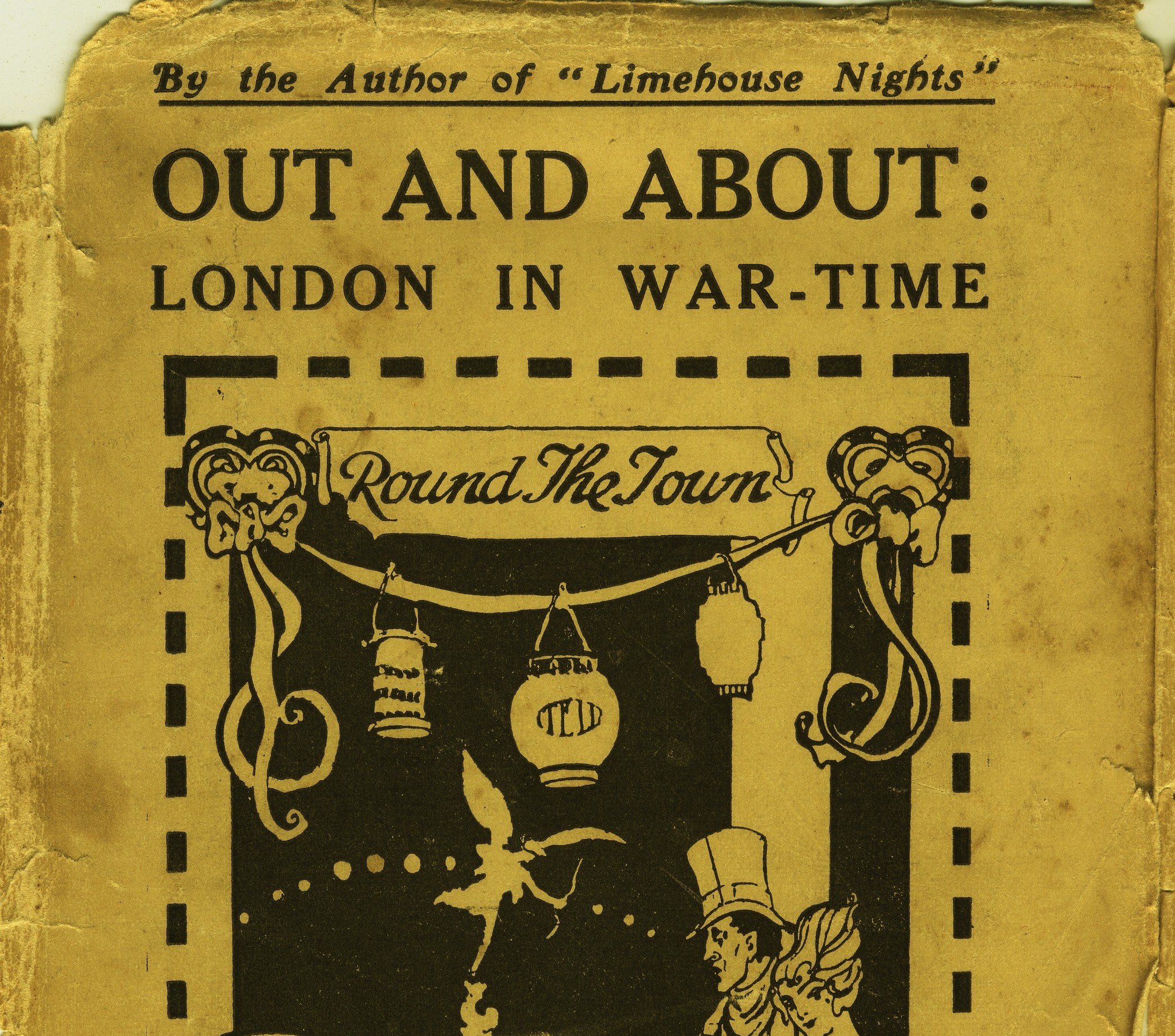

England’s Yellow Peril draws on her previous work on the writers Thomas Burke (best known for Limehouse Nights: Tales of Chinatown) and Sax Rohmer (the creator of Fu Manchu) in Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie: Limehouse Nights and the Queer Spell of Chinatown (2009). She has also looked at the experience of the Chinese in London shortly after the Great War in her book Lao She in London (2012), which examines the influences and milieu that shaped the young Chinese writer Lao She when he lived in London in the early 1920s.

Dr. Witchard is based at the University of Westminster in central London where she lectures in English literature with a special focus on modernism. Her interests in chinoiserie roam from its influence on European poetry and art to the Russian ballet. Her edited collection, British Modernism and Chinoiserie, will be published by Edinburgh University Press in March 2015 .

PF: In 1914 the Yellow Peril was already well established as a concept and a fear for many Europeans and Americans. In England it seems the outbreak of the war in Europe accentuated these concerns and centered particularly around the issues of opium use, gambling, and interracial relationships in the Limehouse Chinatown district. Given that Britain was at war with Germany in France and Belgium, why this heightened concern with a small Chinese community in the East End?

AW: With the outbreak of the war came a panic against foreign “aliens.” The very existence of foreign quarters in the capital threatened the idea of a nation wishing to believe itself socially and ethnically homogenous. There were communities of Italians, Russian Jews, and others in London, but while newspapers now targeted all foreigners living in Britain as “the enemy within” none were so visible as the Chinese. Until this point they had mainly been exoticized as providing relatively harmless “local color”‘ — now their penchant for smoking a pipe of opium was linked to a drug-trafficking menace while the fact that they were a bachelor community made them a focus for accusations of white slavery, the abduction and trafficking of women for prostitution. Of course the labor unions had never been happy about the presence of Chinese workers, but during the war their threat was articulated chiefly as a moral menace.

PF: Despite this hostility the war actually led to the expansion of Limehouse’s Chinese community. Chinese merchant seamen took jobs on British ships freeing up British men for service in the Royal Navy while Chinese-crewed ships brought much needed food, war materiel, and provisions to England. Yet the Chinese were resented by unions, politicians, and many others — why? Was this dislike and resentment a result of pre-war Yellow Peril thinking?

AW: Yes, this was something that stemmed back to arguments posed against Chinese immigration to the United States after the Gold Rush and the fact that Chinese labor could be procured for low wages. Hiring Chinese seamen or domestic workers was a diplomatic minefield during the war despite the 100,000-strong Chinese Labour Corps, hired and shipped out from China to serve on the Western front as manual laborers. After the Armistice was declared in 1918 these men continued to be employed in hazardous mine clearance, filling in the trenches and disposing of the dead, but none were given permits to enter Britain. And then a post-war extension of the UK’s Aliens Restriction Act refused permission to the Chinese seamen who had served in the British Merchant Marine to remain in the country.

PF: Moving on, you say that Thomas Burke and Sax Rohmer can be credited with “inventing the myth that was Chinese Limehouse.” What was the myth? And how did they each approach the district in their own literary ways?

AW: Well between the two of them they covered the spectrum of anti-Chinese prejudice. With his tales of illicit love between Chinese men and white girls in Limehouse, Burke romanticized the Chinese presence in a way that inflamed conservative and eugenicist thinking. Although his fiction appears perhaps benign in comparison to accounts of Fu Manchu and his fiendish plots, it did just as much harm to perceptions of the Chinese.

PF: Burke’s Limehouse Nights was turned down by no less than 12 publishers in 1914 — what was so objectionable about his Limehouse tales on the outbreak of the war? If not for the war and war-related concerns, as discussed above, would Burke’s book have been so controversial?

AW: All of Burke’s rejection letters mention the increasingly conservative moral climate as a factor. This became even more acute after the banning of D.H. Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow for immorality in 1915. What was objectionable about Limehouse Nights was that it offered no condemnation of its theme of interracial love and that it glamourized Chinatown as a resort of bohemian revelry!

PF: Sax Rohmer thought “conditions for launching a Chinese villain on the market ideal” in wartime. Did the prevailing Yellow Peril atmosphere inspire Rohmer or, as I think most people think, did Rohmer create the Yellow Peril with Fu Manchu?

AW: Rohmer didn’t create the idea of a Yellow Peril — that dates from late-19th century concerns, not only about Chinese workmen undercutting white labor but about the rise of Japan and likelihood of a pan-Asian overthrow of Europe. So-called “future war” novels were a significant genre at the end of the nineteenth century and one of the most successful, The Yellow Danger (1898) by M.P. Shiel fictionalizes this scenario. Its protagonist Dr. Yen How (who is half-Japanese, half-Chinese) leads his “yellow hordes” burning and pillaging their way across France only to be headed off at the English Channel by the stalwart Brits. Yen How is clearly the prototype for Dr. Fu Manchu and, while Rohmer’s first Fu Manchu story predates the war, his wartime fiction locates the devil doctor in Limehouse.

PF: In England’s Yellow Peril you have a chapter entitled “Sinophilia.” We hear a lot about Sinophobia these days and the Yellow Peril was a form of Sinophobia, but we hear a lot less about Sinophilia. You suggest that we can see Sinophilia in Burke’s “exotic reek” and that this links him to more highbrow Sinophiles of the time such as Ezra Pound, Laurence Binyon, etc.?

AW: Yes, you might see both sides as orientalist fantasy one way or the other. There is a direct link here from the aesthetic Decadence of the fin de siècle period. Binyon while a serious scholar, who, as Keeper of Oriental Prints at the British Museum, introduced Pound to Chinese art, had published purplish poetry in his younger days and Burke certainly bowdlerises an 1890s vein in his depictions of Limehouse. While intellectuals turned to ancient Chinese culture to revive their tired Victorianisms (“slither” as Pound put it) Burke’s success derived from his rather more populist exploitation of late-Victorian orientalist wallowings. In fact there are direct plagiarisms to be seen in Burke’s stuff and the poetry of the notorious Decadent Ernest Dowson. We should also remember that divisions between high- and low-brow were not so readily made back then[;] in fact Burke’s first Chinatown story was published in Ford Madox Ford’s “advanced” literary journal The English Review, and that Limehouse Nights was initially reviewed alongside James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man!

PF: There’s a real contradiction between concerns about China and the Chinese (at least in Limehouse) and popular entertainment during the war. As you mention London theatre audiences loved chinoiserie fripperies such as the massive revue hit Chu Chin Chow and productions of the pantomime Aladdin. How do you explain this contradiction of a demonization of the Chinese in the East End and yet chinoiserie being celebrated and flaunted in the West End during the war?

AW: I don’t actually see this as a contradiction. Chu Chin Chow gleefully exploits Yellow Peril stereotypes, as does Aladdin. The robber baron Abu Hasan disguised as Chinese merchant Chu Chin Chow is deliciously scary in the same way as Widow Twankey is ridiculous — both allow scope for chinoiserie fantasy that can indulge in and poke fun at such fears at the same time.

PF: Similarly, despite the legal and moral crackdowns on dope and gambling and entertainment in Limehouse, you portray a wartime London demi-monde of nightclubs, bars, and cabarets filled with West End Bohemians and flappers with plenty of opium and cocaine?

AW: Ultimately what was at stake here was the increasing freedom sought by young women — whether they were portrayed as working-class girls consorting with “Chinamen” in Limehouse, or debutantes leading officers astray in Soho drinking dens. There was no turning back from the unprecedented freedoms that wartime afforded young women and this was a [principal] source of Establishment anxiety. They had to be made scared — hence the moral hectoring and, at the bottom line, the Yellow Peril fearmongering.