By Paul French

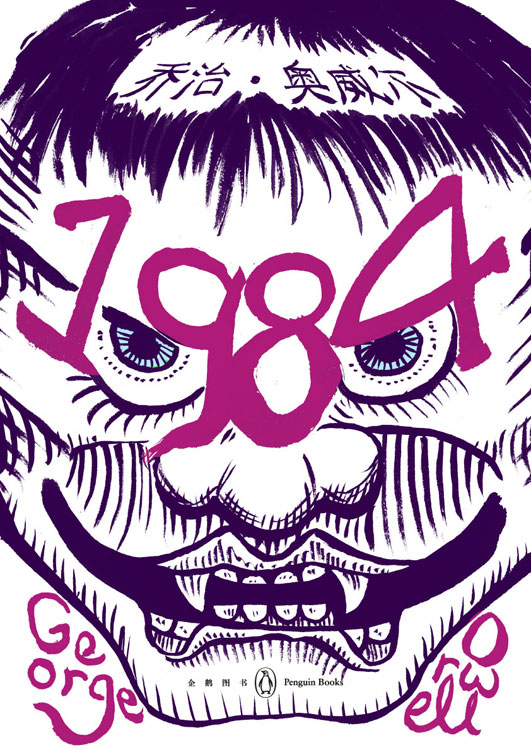

In the wake of new Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s “Third Plenum” — the first policy-focused general meeting he’s presided over since being anointed a year ago — the term “Orwellian” is once again getting a work-out.* It’s long been and remains a great favorite among China writers: the Great Firewall is Orwellian, censorship is Orwellian, the Chinese police are Orwellian, Beijing’s policy pronouncements are Orwellian Double Speak. But while Orwellian may be the most overused eponymous adjective (an adjective derived from a real or fictional person, as you’d know if you’d been paying attention in your English grammar class), plenty of others are available to the writer on China, beginning with that derived from the name of Orwell’s one-time French tutor at Eton, Aldous Huxley, who has been in the news lately due to sharing the anniversary of his death with JFK (and C.S. Lewis).

There has been, in fact, a lively eponymous adjective debate lately among foreign writers and journalists covering China over whether the PRC is Orwellian (repressive and brutal as in 1984), Huxleyite (psychologically manipulative, a society bought off by consumer goodies and where stability maintenance is the primary concern, a la Brave New World), or a bit of both. Over the years, and over numerous events from Tiananmen Square to the riotous opening of a new Apple store, views have swayed between emphasizing Huxley’s “velvet glove” and Orwell’s “iron fist” (as opposed to Jack London’s capitalistic Iron Heel).

Those looking for more nuanced eponymous adjectives can reach for other terms. When discussing society the Chinese people can be Brechtian and detached from the action, or Pinteresque with extreme detachment in the face of absurdity (you could substitute Beckettian if you prefer). Certainly more than one Chinese Foreign Ministry official faced with an awkward question from a foreign journalist has displayed an admirable Pinteresque pause in the past. The unkind see Chinese society as full of Asimovian robots performing endless Olympics opening ceremonies. For the new China commentator faced with the overwhelming onslaught of China, Daliesque – denoting the surrealism of the whole show – is popular (some have suggested mixing surrealism with alienation to become Murakamiesque, but it hasn’t caught on yet), and the science-minded eponymous adjective lover might see the whole thing as a Baconian cipher (the message being hidden in the presentation rather than the content).

The China debate of course moves fast, and so can at times appear almost Joycean (in the sense of rapid subject change as opposed to lyricism – China is rarely lyrical) and more than one commentator has displayed a Vonnegutian approach, relying on gallows humor to try to decipher Beijing. I myself admit to having reached for the notion of understanding China as akin to going “through the looking glass,” though Carrollian sadly doesn’t really work as an eponymous adjective.

Business writers really like Kafkaesque (well, his books were short) and all that endless shunting from office to office for permits, opaque laws and never getting a straight answer is reminiscent of poor old K. as he strives to untangle the bureaucracy of The Castle. Younger commentators might go for Gilliamesque (surreal and a tad Kafkaesque, in a Discworldy sort of way).

The debate around China’s future brings forth a whole new slew of eponymous adjectives, often written in a Hemingwayesque style. China could be seen as Byronic (seemingly ideal but with a hidden dark side). More often the analysis tends to the Lovecraftian, courtesy of the early H.P. Lovecraft and portending horrible future prospects, or Ballardian, envisaging a definite dystopia with a veneer of science on top (a Ballardian coffee with a Huxleyite cream if you like). Ballard may be onto something as he was at least born in Shanghai; and all those empty swimming pool motifs engendered in his childhood during the Japanese occupation still seem of-the-moment when writers tour those half finished luxury villa developments on Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road. Of course those looking for The Shape of Things to Come in China often reach for Wellsian — and that includes those who predict it’ll all end in a War of the Worlds.

The Victorians are useful when describing China’s factories – Dickensian is perennially popular. But if you really can’t make your mind up about China, then, without doubt, Shakespearian is the eponymous adjective for you. Take your pick – comedy, tragedy, farce? King Lear gets dropped a lot when the leadership is being discussed, as does Julius Caesar, but I don’t think Romeo and Juliet got a mention in the Bo Xilai/Gu Kailai saga.

Of course all this can get a bit tedious, a bit boring, a bit Franzenesque (okay, I made that one up). One hopes of course that the best writing about China should be Proustian (ornate, detailed, rich with memory and recollection), but it’s not always, sadly. And finally, do remember the eponymous adjectives that nobody outside China uses are Marxist, Leninist, and certainly not Trotskyist – but none of them wrote fiction so they’re no fun.

So go ahead next time you’re asked to write an article on China (and with so many words spilled on China you will eventually be asked) – select an eponymous adjective, press send, sit back and relax – someone out there will agree with you.

A very partial list of Orwell-related commentaries on China can be found by clicking here, here, here, here, and here.