Truth is stranger than fiction, Mark Twain observed, because it’s not obliged to probability: a novel has to make sense. Twain’s axiom, though, depends on a fragile bargain. When life takes on the appearance of fiction — what need is there for novelists?

Consider a couple of possible plotlines. In Henan province, once the epicenter of Mao Zedong’s calamitous Great Leap Forward, a wealthy fanatic erects a giant gold statue of the late leader in a barren field; the half-million-dollar colossus is demolished just before reaching completion. Over in landlocked Jiangxi, a businessman running a green energy company is gifted an endangered eight-ton whale by a fellow boss in Zhejiang; the rotting carcass is set aside for a staff bonus, but after its foul smell draws media attention, local authorities declare its meat is destined for dog food.

Ample material one might think for any novelist to portray the runaway materialism and inverted rationale of everyday Chinese life, but for the fact it’s already been taken — by real life. What’s a writer to do? Up the ante. Beijing writer Ning Ken devised the term chaohuan (the “ultra-unreal”) to describe a long-emerging genre adopted by some of the country’s best writers. “The more true to reality fiction is these days, the more avant-garde it will seem,” Ning observed in a recent essay.

Preoccupied with themes of monstrous authority and accelerated time in a digital age, chaohuan lays claim to being a uniquely Chinese form of magic realism, its writers more humorous in style than their more melancholic Latin America counterparts, yet all the more “real” for it.

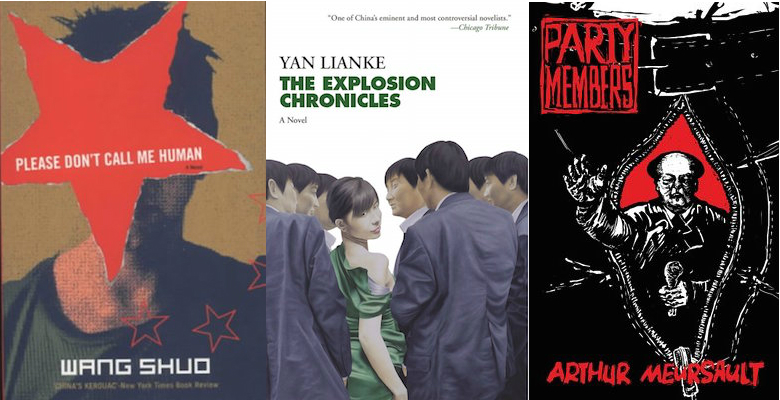

Admirers of Lu Xun (China’s greatest 20th-century writer) and Pu Songling (a literati figure from several centuries earlier) might argue that this sort of stuff has been around for ages. Elements of it can certainly be found in works such as Mo Yan’s boozy Republic of Wine (1992), Yu Hua’s ribald Brothers (2005), Koonchung Chan’s hallucinatory The Fat Years (2009) and last year’s Year of the Goose by Carly Hallman. Wang Shuo’s “vulgar” and “reactionary” Please Don’t Call Me Human (2000), though, was perhaps the first work to go full chaohuan (those adjectives, of course, come courtesy of censorious Chinese Communist Party critics; readers bought 10 million copies).

With an absurdist plot in which a “Chinese and Foreign Free-style Elimination Wrestling Competition Organizing Committee” attempts to gain face by resurrecting a master Boxer for a then-upcoming summer Olympics, Please Don’t Call Me Human offered all the vital seed elements of the genre: Bombastic officialese; the surreal grafting of modern capitalism onto Leninist rhetoric; and self-destructive face-saving taken to lunatic conclusions. The book ends apocalyptically, and earned Wang an accolade more precious than a coveted PRC Lu Xun Literary Award: the unswerving disapproval of censors, who banned his work and directed all future royalties to the pirate press.

One of the latest examples of chaohun, which like Year of the Goose comes from a foreign rather than Chinese author, is Arthur Meursault’s Party Members, a debut novel that promises readers “designer handbags, sex, karaoke, and shady property deals… a picture of modern China unlike anything seen before.” It seems ordinary enough at first (when has a recent portrait of China not featured some combination of the above?), but the author takes vicious pleasure in proving otherwise.

Our protagonist is Yang Wei, a low-ranking “one of a billion” official in the 88th-tier hellscape of Huaishi, an amalgamation of every rank-a-dank provincial city a PRC resident might have the misfortune to be sent to a conference in. Party Members (a 236-page book, published by Camphor Press) portrays a country toiling under the yoke of evil and incompetence; the ministry’s clock strikes thirteen only because “there had been a mix-up during the clock’s manufacture and no one could be bothered to change it.” There’s a splendid set piece in an utterly unremarkable and thoroughly overpriced restaurant (the embrace of mediocrity and pretenses at sophistication are a chief target of Meursault’s contempt). Here, Yang and rival “Little” Qi exchange passive-aggressive parries, each attempting to score points for the benefit of their bored wives. A revelation in this eatery’s dismal bathroom is the engine for the Metamorphosis-like plot.

Meursault enjoys scoffing at China’s routine mix of officious absurdity and extreme banality, such as the dreary offices where Yang and fellow cadres slack off, and his docile boss is known as “Great Wall” as his incorruptible nature has blocked the careers of so many grasping underlings. Surrealism soon swamps subtlety, though: Yang has a talking penis and the author is determined to follow this development to its bitter end. Part chaohuan, part Grand Guignol horror, part rant, Party Members is also, alas, often part bore.

Unlike Meursault, the acclaimed lampoonist Yan Lianke is an old hand at summoning the bleak mockery to critique what he calls the “incomprehensible absurdity” of events such as the Cultural Revolution (in Serve the People!) or the Henan AIDS blood scandal (in A Dream of Ding Village). In Yan’s latest, The Explosion Chronicles (translated into English by Carlos Rojas, published by Grove, and clocking in at a substantial 457 pages) he turns his eye on the last three decades’ economic boom via a rural village that violently expands into a teeming metropolis. The town is Explosion, a translation that alludes to both China’s perilously rapid growth and its catalyst, the briefcase stuffed with cash (“explosive gifts” in Chinese).

The townsfolk, named Kong, all claim to be descendants of Confucius, “though there are no genealogical records to corroborate this claim,” but the values of this dynasty are more in keeping with the likes of Yang Wei, Meursault’s avaricious anti-hero, than the venerable sage. There is plenty of emperor worship and ancestor obsession, but what truly binds this clan together is ambition — explosive ambition. Skyscrapers and airports are flung up in days, while flowers miraculously bloom in winter, watered by blood and official ink. The sense of impending cataclysm mounts with every extraordinary feat and godlike subjugation of nature.

Ultimately, the greatest misfortune falls on Yan himself. He sees his “mythorealism” as narrating a tragic misfortune; many of his foreign readers still consider him a humorist. Perhaps the last laugh will be on them. In the West, the last year has marked a time when things appeared to stop making sense. As the persistence of chaohuan demonstrates, it’s a situation that many Chinese have wistfully tolerated for decades.