By Paul French

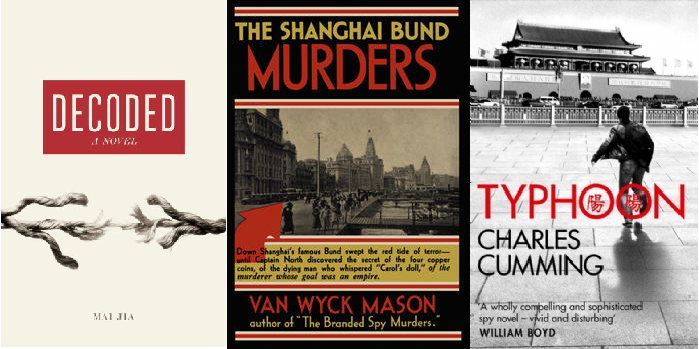

One of the most noteworthy books set to hit the U.S. market next week is Olivia Milburn and Christopher Payne’s English translation of bestselling Chinese espionage author Mai Jia’s latest thriller, Decoded, which was published in other markets last year and has already generated a good deal of interest in the U.K. This is just the latest development in a broader publishing tale: the resurgence of interest in Asia generally, and China specifically, as a settings for stories of intrigue.

One sign of this phenomenon has been the appearance of recent thrillers with present-day Asian locales, such as Charles Cummings’s Typhoon (2010) and Ridley Pearson’s The Risk Agent (2012). Both of these were set in a contemporary Chinese milieu where shopping malls proliferate, post-socialist but still Communist surveillance mechanisms are in play, and industrial espionage is a feature of the international business scene. Scandi-crime top sellers Jo Nesbø and Henning Mankell have recently made brief excursions to East Asia. A China of the near future features in the thrillers Dragon Strike (1997) and Dragon Fire (2000), both by Humphrey Hawksley. And even Asia as it was, rather than as it might soon be, can still cast a spell, as shown by David Downing’s choice of pre-WWI Shanghai as the place where the plot of his recent Jack of Spies (2013) unfolds. Old Shanghai has long held a special allure for espionage writers, and other recent books prove that its attractiveness endures: cases in point range from Adam Williams’s trilogy The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure (2004), The Emperor’s Bones (2005) and The Dragon’s Tail (2007), to Tom Bradby’s The Master of Rain (2002), or Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans (2000) — all of them set in the city between the 1920s and 1950s.

Given this recent interest in China and Asia among writers interested in spies, this seems a good time to look back at some of the Asian adventures conjured up by greats of the espionage writing game of earlier generations. Here is a sampler of choice works, a mix of novels by famous past masters and noteworthy books, by now little known, but in their time influential or at least popular contributors to the genre:

The 1930s saw China emerge as a destination for espionage in novels. Now almost forgotten, but popular at the time, was Francis Van Wyck Mason’s The Shanghai Bund Murders (1933) — full of warlords, gunrunners and damsels in distress. Van Wyck Mason, a Bostonian novelist, had a long and prolific career spanning 50 years and 65 novels. His mysteries were filled with characters from the American government’s intelligence services, a world he knew well, having lived in Berlin and then Paris, where his grandfather had served as U.S. Consul General. As a teenager he served in first the French, and then in the American army as a Lieutenant during World War One. After the War he attended Harvard where he was mistakenly arrested for homicide after borrowing a dinner jacket; he was wrongly identified as a waiter wanted on murder charges. He published his first book in 1930 featuring his proto-James Bond character Captain Hugh North, a detective in G-2 Army Intelligence. This was his seventh in the Hugh North series and he eventually ends up solving the Shanghai Bund murders and nailing the western gunrunning baddies who were clearly based on the many westerners running guns along the China coast at the time.

Shady foreigners in Peking who might just be involved in espionage also feature in Vincent Starrett’s Murder in Peking (1946). Set before the war, murder strikes an elegant foreign dinner party in Peking. During the course of the investigation the enquiries move in and out of the Legation Quarter, into the temples of the Purple Mountains where the foreigners picnic, and through the backstreet hutongs of the city. Starrett visited China many times and knew Peking well, and it shows.

Wartime China is the setting for any number of novels but the most widely read at the time, and one for which espionage is at its heart, is Jan Maclure’s Escape to Chungking, published in 1942 and a popular book in Britain in what would nowadays be called the ‘YA’ market. It’s a sort of World War Two Kim with 14-year-old Christopher, or Kit, discovering that his mother is party to hidden military secrets in Japan. Kit finds his mother’s friend nearly dead after trying to take secrets to the British and is handed a package containing the formula for a new kind of explosive before the friend dies. He takes this on a long journey from Japan to Chungking to deliver the secrets to the Chinese government battling Japan from the head of the Yangtze. The author remains a mystery, with no other books listed under her/his name, but was obviously someone who knew China, Japan and Asia well, as the descriptions of the Chinese countryside, as well as Tokyo, Singapore and Malaya, are spot on.

I inherited my mother’s old wartime book club copy that she read as a young teenager in Blitzed London and in these days, when it’s fashionable to say that China was a forgotten element in World War Two, the bestselling success of Escape to Chungking perhaps indicates a greater awareness of the war in China than many assume.

Murder and espionage in pre-revolutionary China became popular themes, and remained so until the Bamboo Curtain fell and the idea of a white spy running round Mao’s China became impossible to imagine. Authors could not get access to research and writers looked elsewhere — to other countries and other historical events — for inspiration.

Pre-revolutionary China would have been perfect territory for “Greeneland”, but it was not to be. Early in his career, Graham Greene did pen a play featuring spies and kidnapping in Manchuria, but never finished it, didn’t like it and destroyed it. He had been fascinated with China since he was a boy and read the now long forgotten Captain Charles Gilson’s The Lost Column, a book published in 1909 about the Boxer Rebellion. After school Greene joined British-American Tobacco in the 1920s and enrolled in Chinese language classes at London’s School of Oriental Studies, where his teacher was none other than a young Chinese writer sojourning in the capital, Lao She. Of course Greene did eventually return to Asia in the masterpiece that is The Quiet American (1955) where, around the time of Dien Bien Phu and the French retreat from Indo-China, the hard bitten English hack Fowler drinks away his career on Saigon’s rue Catinat, until he encounters the mysterious American, Alden Pyle.

That early retreat from empire in Indo-China was to inspire other writers, not least Nicholas Freeling, the creator of Amsterdam’s Commissaris Van der Valk, who in Tsing-Boum! (1969) uncovers a murder in sleepy Holland that takes him back to the disaster at Dien Bien Phu and trouble with the French intelligence services.

China was closed but South East Asia and Hong Kong were still accessible to writers, and one master of the spy genre, Eric Ambler, ventured across the region, taking in the newly free state of Indonesia as well as Singapore and Hong Kong in Passage of Arms (1959). The clients are different after the war but western gunrunners are still active and the British and American intelligence services still want to be part of the action. Ambler’s descriptions of Hong Kong are particularly acute. Speaking of Hong Kong, of course, it’s worth re-reading James Clavell’s under-appreciated follow up to his best seller Tai-Pan (1966) — Noble House (1981), where the taipan of Struan’s trading company, Ian Dunross, finds himself in the 1960s struggling to maintain the family firm from interference by Soviet, American and British spies.

We can’t not acknowledge Ian Fleming and Bond, despite being so well known. Fleming himself knew Asia reasonably well. Of course his brother, Peter, was an inveterate traveller to China and wrote his own bestselling books on the country (News from Tartary (1936) and One’s Company (also 1936)). Less well known, though recently republished, is Fleming’s collection of travel articles for The Sunday Times, Thrilling Cities (1963), where he visits Hong Kong, Macao and Tokyo, among others, in 1959-1960. Profitable research time!

We end our short trip into the earlier years of Asian espionage writing, with a true classic — John Le Carré’s The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), the only outing by George Smiley to Asia and the second book in the Karla Trilogy. Hong Kong as the western listening post on Red China, British intelligence determined to hang on and still count in an American-dominated Cold War espionage world, opium still a valuable commodity to China and a truly memorable description of little known Vientiane. Any (male) visiting espionage fan to the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club will have stood at the club’s urinals and looked out the windows over the view that greeted the gangly twenty-seven-year-old, and badly hungover, Vietnam War reporter Luke as he stands in the same spot, watching a typhoon approach to engulf the Colony, in the opening pages of the novel.

China and Asia are still “sweetspots” to western espionage authors and now, it seems, they are being joined by a new crop of Chinese spy writers. Long may the tradition continue!