By Paul French

Shanghai’s sin districts that catered to foreigners were many and varied. They appeared moments after the city became a treaty port in the 1840s and survived through to the 1950s. Whoring at the brothel shacks in Hongkew, gambling at the first race course on Honan Road, illicit betting at the adjacent Fives courts and knock-down-&-drag-out shamshu bars in Pootung (Pudong), were popular pursuits for sailors, all up and running by 1850. Sin existed across the city — in the French Concession and the International Settlement, around the edgelands of the foreign concessions in the Western External Roads (Huxi), as well as the Northern External Roads that ran across the Settlement’s borders from Hongkew (Hongkou) into Chapei (Zhabei). All of these districts shifted, morphed, rose, and fell over the decades thanks to a variety of factors — from suppression by the Chinese and/or foreign authorities, and as a consequence of the Second Sino-Japanese War after 1937, the liberation of Shanghai from the Japanese in 1945, and the arrival of the communists in 1949. All these places were the subject of legend and anecdote, exaggeration, and not a little official embarrassment. The sin districts fill the pages of the files of the Shanghai Municipal Police and the jotter books of the Garde Municipal in Frenchtown. They were patrolled by the Japanese Gendarmerie that, in the late 1930s, controlled the Western and Northern External Roads, and by the Chinese police that governed the fringes of the settlements beyond foreign control. All saw prostitution, drug abuse, and gambling alongside murders, mayhem, and bloodletting. The stories are legion, and the tale of the murder of Eliza Shapera in 1907, of which there is an excerpt below from a new anthology of true crime writing, is but one of the many, many unsolved murders among Shanghai’s floating multi-national foreign underclass.

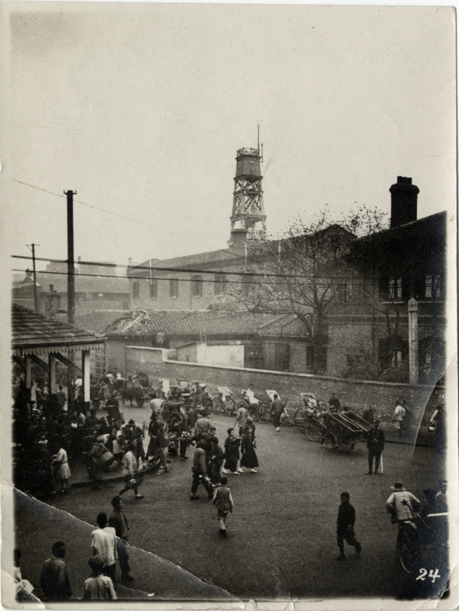

To recover such stories is to retrace the networks of old Shanghailander society — not those of the taipans and committeemen, the missionaries and paper-shuffling officials, but rather of the ever-present but invariably only briefly glimpsed in most histories, underworld of the city’s sin economy. Eliza Shapera’s story begins and ends in the so-called Trenches district of Shanghai, in the Northern External Roads centerd around Scott Road (now Shanyang Lu). At its high point, roughly from the start of the twentieth century to around the time of the First World War, the Trenches was home to an estimated 300 brothels, both foreign and Chinese, running along Scott Road towards Hongkew Park (now Lu Xun Park). Unsuspecting new arrivals to Shanghai found unscrupulous rickshaw pullers who would deliver them to Scott Road to be mugged, robbed, and beaten up by the violent Hongkew gangs (themselves reflecting Shanghai’s multinational underclass — Shanghainese, Cantonese, Jewish, British, Indian, American, Portuguese, among others) that controlled the area. The ever-enquiring William Willis, an anti-White Slavery campaigner who visited Scott Road in about 1910, claimed that, “If a drunken man or licentious European reprobate enters these quarters, the chances are ten to one against his ever coming out.” This was Eliza’s world.

Other areas came and went. Before the Trenches there were casinos, brothels, and bars to the west of the city near Siccawei (now Xujiahui). American-run dancehalls and casinos, such as The Alhambra, drew the curious in horse-drawn carriages in the late-nineteenth century. Early establishments, such as The Del Monte, lasted until the late 1930s when the area morphed into the lawless Shanghai “Badlands” around the triangle of Avenue Haig (now Huashan Lu), Edinburgh Road (Jiangsu Lu) and the Great Western Road (Yan’an West Lu). Nightclubs, cabarets, casinos, opium dens, and brothels proliferated, protected by the Japanese and the puppet collaborators of Wang Jingwei who “taxed” them for profit. Squeezed up against each other in hastily-erected structures were Farren’s, the Arizona, The Gardenia, the Ali-Baba, the Zau Foong, the Six Nations, the Monte Carlo, the Yih Loo, the Hollywood, the St. George’s, the Argentina, the Shanghai Garden, the Eventail, and others.

Blood Alley (officially Rue Chu Pao San, and now Xikou Lu) in Frenchtown became a legend among sailors, soldiers and curious slummers. The Palais Cabaret, the ’Frisco, Mumms, the Crystal, George’s Bar, Monk’s Brass Rail, the New Ritz, and The Manhattan all vied for business. Love Lane (Wujiang Lu) in the Settlement saw the rise of the St. Anna’s, Van’s Dutch, and Margaret Kennedy’s long-lived brothel where the girls didn’t work on Sundays. Both strips lasted until the 1940s. At the start of the twentieth century the American-run brothels of Kiangse Road (Jiangxi Lu) were the most exclusive establishments — the street referred to simply as “The Line.” It died out largely with the arrival of the White Russians and a collapse in prostitute prices as volume very nearly (but never quite in Shanghai) outstripped demand. Brothels and bars for sailors proliferated in Hongkew along Wayside (Huoshan Lu) and Broadway (Daming East Road). They were joined in the 1930s by Jewish-run bars and cabarets that clustered on the edge of the ghetto. Some lasted till the early 1950s when foreign ships still called at Shanghai and sailors still got shore leave.

Often it is real people who link the areas; blood links usually, the free flowing kind …Gracie Gale dominated “The Line” as its premier Madam from the early years of the century until she saw the bottom fall out of the high-end bordello business and blood on the streets of Shanghai in 1927. She slit her wrists rather than enter a new era of commoditized sex — modernity had limits for Gracie. Sammy Wiengarten, a Romanian, trafficked women from Eastern Europe to the Trenches before World War One, ran clubs in Chapei afterwards, and was murdered in 1936 counting his Christmas take after-hours. Al Israel came from California and pioneered the nightlife of the Siccawei Road and Huxi. His Del Monte club went from tree-lined streets on the fringes of the city in 1900 to the heart of the Badlands of the Japanese occupied city in the 1930s. That transition was bad news for Al, shot dead at his desk above the casino floor of the Del Monte in 1937. And finally Stuart Price, a man who stepped off a boat and entered Shanghai in the nineteenth century. He killed a customer at his notorious Alhambra dancehall in 1906 (whisky and opium over the downstairs bar, girls and roulette upstairs), got off on a technicality, and survived the vicissitudes of fifty years of Shanghai vice to become an old man who’d seen it all in a Japanese internment camp in World War Two.

New times brought new customers and new red-light areas. By 1945 the Badlands was deserted, most of the giant casinos and nightclubs shuttered, the “Trenches” mostly destroyed by Japanese bombing, “The Line” a memory but, as Allied troops flooded into newly-liberated Shanghai, scores of new bars and brothels were opened by foreign “entrepreneurs” — Black Eyes, the Victory Bar, the Dollar Bar, the Diamond Bar, the Lear Bar … they lasted but a few years and all were gone by the early 1950s.

But this tale takes place in the Trenches: Shanghai’s pre-Great War low-end red-light area of trafficked women and brutal pimps living in appalling conditions. Before the Rue Chu Pao San became Blood Alley, a world away from the plush bordellos of The Line, and three decades before Huxi became the “Badlands” there was Murder in the Shanghai Trenches…

Scott Road, Shanghai International Settlement, Wednesday 18th September, 1907

At 7.45pm a disheveled young woman of apparently Russian or East European origin burst into Hongkew Police Station on Woosung Road and reported the murdered body of a white woman at No.56 Scott Road. Sergeant John O’Toole grabbed P.C. Cornelius Hamilton and the two Shanghai Municipal Policemen set out to the address leaving the distraught woman under guard at the station.

When O’Toole and Hamilton reached Scott Road they found a large crowd gathered outside No. 56 including one Indian man, apparently drunk, shouting and screaming in the middle of the road. They ignored him and headed immediately inside the narrow detached house and made their way upstairs to the front facing bedroom looking down onto the crowd below.

Sergeant O’Toole was just shy of 30 and had left Ireland and the Royal Irish Constabulary to join the Shanghai Police in 1900. Since arriving in the International Settlement, he had seen his share of dead bodies among the driftwood of life that somehow made its way to the great foreign-controlled centre of commerce for eastern China and the Yangtse Delta. For P.C. Hamilton, barely out of his teens and arrived in Shanghai from rural County Limerick just months before, this was his first murder.

In front of them, on the room’s only bed was the body of a dead European woman, sprawled across the mattress and with a pillow partly covering her face. O’Toole and Hamilton then moved back out into the corridor to check the back bedroom of the house. Nobody was in that room, though the window was ajar but all appeared to be in order. They heard a noise behind them, returned and found the Indian man from downstairs had entered the house and come upstairs. He had removed the pillow from the victim’s face. He started to turn the body before the policemen grabbed him and ejected him from the room, ordering him to go downstairs and leave the house. P.C. Hamilton went down with the man and detained him outside.

O’Toole felt for a pulse and found nothing. The woman was wearing a tattered nightdress and white stockings loosely tied with ribbons. The charge-room at Hongkew Station had contacted the senior detective on duty and O’Toole was to secure the crime scene, touch nothing, and await the arrival of the designated investigating officer.

Detective-Sergeant Thomas Idwal Vaughn, a stocky Welshman, had joined the Shanghai Police in 1900 in the same intake as O’Toole, but had since made detective. He arrived at 8pm and found a large crowd of excited and argumentative European women in the hallway of the building shouting in what he believed to be Russian. He called up to O’Toole, told him to come downstairs and clear them out of the house while Vaughn inspected the body.

Vaughn noted that the body was cold and lying on its left side, partly sprawled across the bed. It smelt of putrefaction, which indicated she had been dead some time. The autumn weather in Shanghai was still mild, the room’s window was slightly open and the room stuffy, which could have accelerated the decay in the warm room. Her legs were bent at the knees, and just above the ankles, were tied tightly together with a towel. Around her neck was another towel, tied in a reef knot, and a twisted curtain that had clearly been used to strangle her. There was heavy bruising around her neck. Her arms appeared to have been forcibly pulled back behind her as if they had been held there as she was strangled. There were bloodstains on the curtain and towel, which had been left slack after asphyxiating her. The woman’s face was black and swollen and she had heavy bruising around her left eye and further bruising under her right eye. Her false teeth had fallen out and were lying next to her on the mattress. The dental plate was broken. Next to the bed were three more blood stained towels. The sheet covering the mattress was also blood stained as were a pillow by her head and a beige shawl lying nearby.

Both the bedroom and the other upstairs back room appeared to be untouched apart from the murdered woman. Vaughan went downstairs to investigate the rest of the house. He found the downstairs back room, the house’s living room, ransacked. A large travelling trunk, seemingly filled with clothing had been upturned and emptied and the clothes strewn about the room. A tray from inside the trunk had been removed and was lying on a small bed in the corner. Clearly the entire room had been searched and all the cupboard drawers and several boxes in the room opened and the contents thrown out. However, none of the heavier furniture had been moved, no crockery or glass was smashed and Vaughan concluded that while the ransacking had been thorough it had been conducted quietly.

Completing his preliminary examination Vaughan took hold of the corpse and lifted it up to check if there was anything underneath. He’d found no weapon that could have made the bruising around the woman’s eyes so far. As he lifted the corpse he saw something drop onto the bed from inside the stocking of the dead woman – a handkerchief with one corner knotted. He picked it up and unfolded it to find two sovereigns, two American five-dollar gold pieces, a Korean 50 cent coin and a small gold locket and chain.

Murder in the Shanghai Trenches by Paul French is contained in the newly published Truly Criminal (The History Press, 2015), an anthology of true crime writing from the UK Crime Writers Association.