By Mengfei Chen

Is it still a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife? Perhaps he’d rather spend that fortune on bottle service and club bunnies. Certainly, modern day Lily Barts need not die young, alone and poor because they nixed a number of suitable suitors — not if Sheryl Sandberg has anything to say about it.

Great nineteenth century novels built on the question of “will he propose and will she say yes” live on, but mostly as bonneted costume dramas on the BBC. They seem like historic relics in the age of the pre-nup and easy divorce.

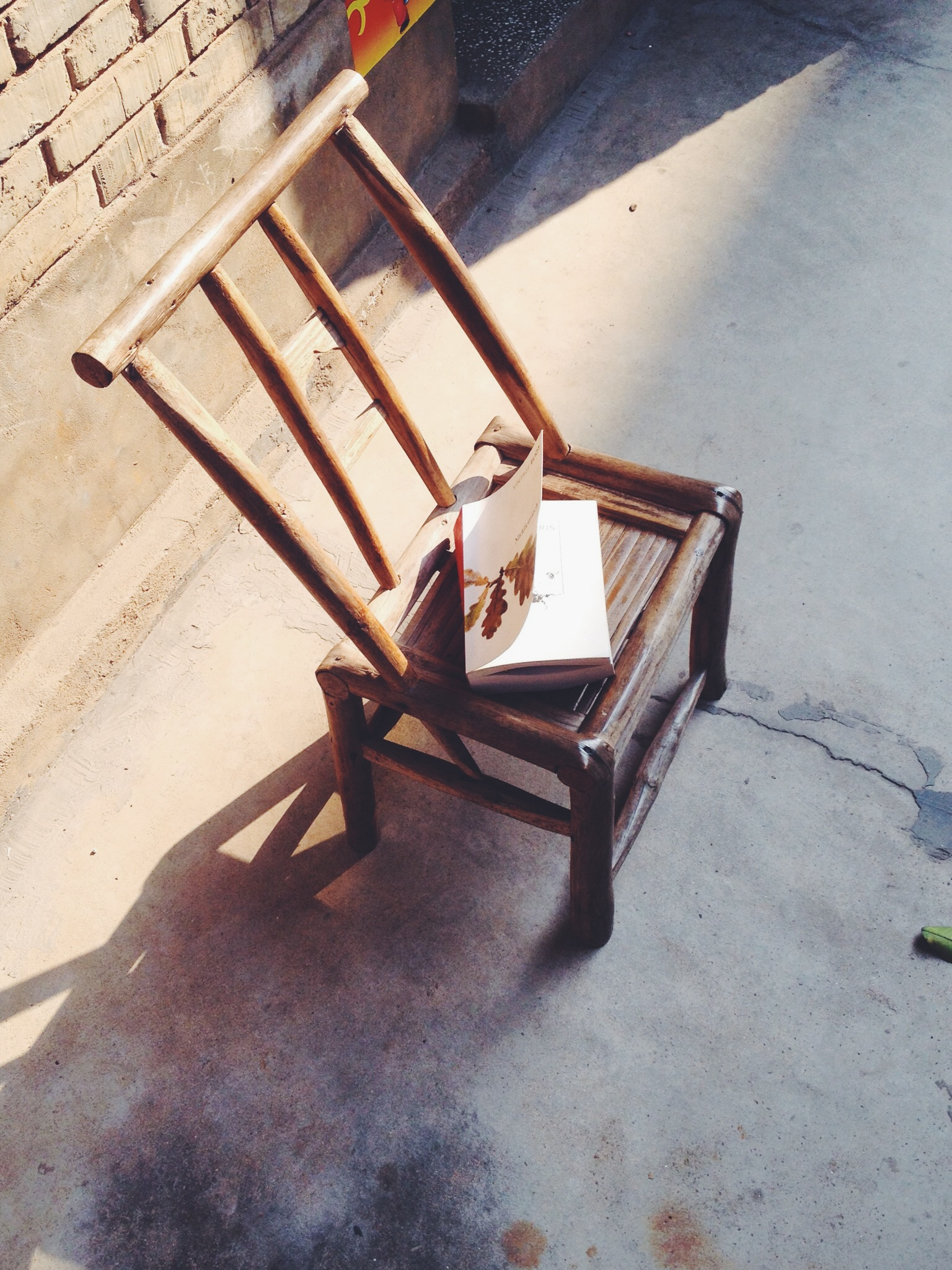

When I took George Eliot’s Middlemarch on my trip to spend Spring Festival with my grandparents earlier this year, I thought I was packing a work of historical fiction. It was holiday reading. I wanted to take advantage of the long journey home (17 hours by train each way, bracketed by another two hours on the newly built two-lane highway dodging tractors, overloaded long-haul trucks and the occasional confused water buffalo) to cross the book Virginia Woolf called the only novel written for adults off my literary bucket list. I did not expect the book, which charts with great sensitivity the marriages, successful and otherwise, of several couples in a 19th century English country town, to resonate so powerfully with the lives of people living in a 21st century Chinese one.

¤

Xinggan, the town in Jiangxi Province where my grandparents live, is a dusty place that has a knockoff fried chicken restaurant because KFC couldn’t be bothered to go there. It’s still possible to grow up in Xinggan thinking a cherry is an exotic fruit. Many Theresas, to misquote Eliot’s prelude, have been born there “who found themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action.”

Everyone who wants more from life than half-heartedly checking for stowaway candy bars at the grocery store exit gets out. My father did. As did his sister and brother. Like many others in China, they return home once a year (at most) during the weeklong Lunar New Year holiday, China’s Thankschristmukkah, the most important time for family reunions.

For a week, my grandparents’ house filled with children (three of four) and grandchildren (five of six) returning from lives in China’s big cities. We watched TV, set off firecrackers, went to visit the white elephant-GDP boosting municipal civic center, and fought over the limited supply of hot water.

We also ate. My grandmother stir-fried a small menagerie of fish, fowl, cows, pigs and some sort of wild animal apparently legally consumable in only a select number of provinces in a giant wood-fired wok. When my cousins and I pleaded for more vegetables, we were heard—and promptly ignored. It’s not a real New Year without the chicken, grandma said.

The time between meals was spent chatting with visitors. Neighbors, relatives whose exact relationship to me would have been a Victorian novelist’s delight to chart, high school classmates of my aunts and uncles, and the man who wired the electricity in my grandparents’ home in exchange for two bags of rice and some oil coupons — all stopped by to catch up.

What did they talk about?

Marriage. They talked about marriage in ways that seemed lifted straight from the pages of the 140-year-old book I was reading.

Was that Mrs. Cadwallader speculating on the effect that too much education would have on the marital prospects of the neighborhood beauty? Mr. Brooke sharing with satisfaction the size of his daughter’s dowry? Mrs. Vincy evaluating the property and salary of a would-be son-in-law? No, it was their Chinese kindred spirits, Mr. Chen and Mrs. Zhao and Mrs. Gu.

One mother predicted the end of her son’s five-year relationship by spouting a common Chinese proverb about like marrying like. Her husband makes a decent but modest living renovating the homes of migrants whose remittances have contributed to an odd fashion for Roman columns in the area’s farmhouses. However, while the family is now firmly middle class, having sent both boys to college, they are far lower on China’s class totem pole than her son’s second-generation-rich girlfriend. The social standings of the families, all those present agreed, were too mismatched for things to work. Catching an heiress, it turns out, is not always cause for celebration.

Another matchmaking mama planned to gift her daughter with an apartment and a six figure check on the occasion of her wedding — a bride price to ensure her independence should the marriage go wrong.

There was little talk of personal compatibility, more of marriage as the fulfillment of a social and familial obligation, “an outward requirement” of adulthood, as one of Eliot’s characters put it. There was more talk of relief than happiness.

Many parents seemed willing to field any candidates as suitors for their daughters as long as these men ticked off a series of requirements: employed, preferably at a state owned company, in possession of apartment, car, most teeth and some wits. They would have seen nothing unusual in Middlemarch’s town beauty’s belief that “it was not necessary to imagine much about the inward life of the hero, or of his serious business in the world,” so long as “he had a profession and was clever, as well as sufficiently handsome.”

When my own family turned to me and cautioned that the time for being picky was coming to an end (My aunt: “Mengfei, are you familiar with the term shengnü?”*), I was only able to offer the unhelpful suggestion that perhaps it would be easier to auction everyone off on Taobao.† George Eliot, I’m sure, would have come up with a better answer.

Mengfei Chen was born in Nanjing, China. She spent several years in Xinggan, before moving to Southern California. She currently lives and works in Beijing.

*As regular Los Angeles Review of Books readers know, thanks to a recent review by Mei Fong and a blog post by Lu-Hai Liang, this is a disparaging term for unmarried women over twenty-seven years old. Roughly equivalent to the Victorian term “spinster,” it literally means “leftover women,” sharing a first character with a term for leftover food (shengfan).

†A Chinese website that is like EBay plus Craigslist on crack: according to a recent BBC article, products range from live scorpions, to gaming credits for World of Warcraft, to a pretend-boyfriend to bring home to the parents over Spring Festival.