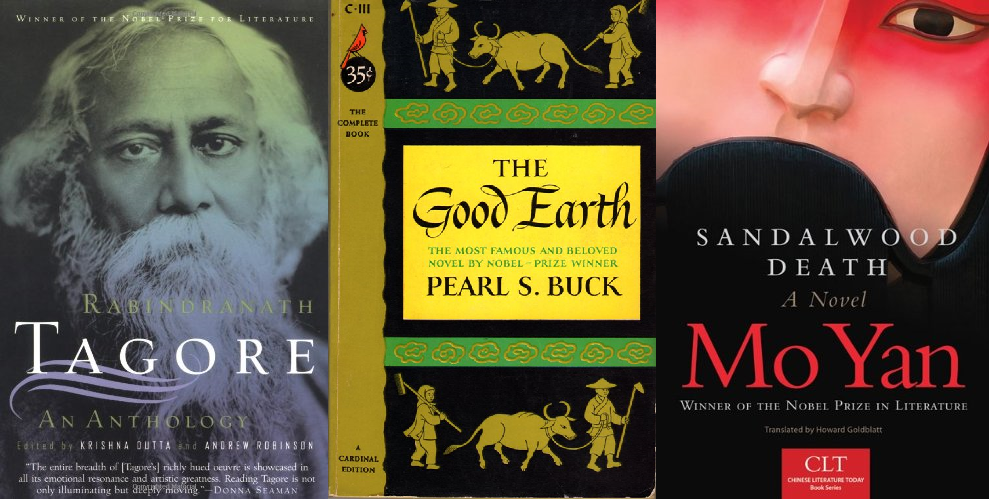

The title of this post lumps together three writers I’ve begun to think of as a trio, though I can certainly understand why some readers might think of them as having precious little in common with one another. Only the first was a major poet, after all, only the second wrote a novel that became a major Hollywood movie, and only the third’s career has involved navigating the challenges of writing in a Communist Party-run state. Tagore published such a prodigious amount that his page count leaves even those of the other two very productive writers far behind; only Buck was a woman; and only Mo is alive. Lists of contrasts like these could be extended almost indefinitely. And yet, thanks to my recent activities as co-editor of the LARB’s Asia Section and a writer working on a book about China in 1900, respectively, I’ve been ruminating a lot lately on two very different connections between them.

Let’s begin with the LARB side of things and the more obvious of the two ties between Tagore, Buck, and Mo — namely, that all three are Nobel laureates. How does the LARB come in here? Well, I’ve been working with Megan Shank, my Asia Section co-editor, on commissioning and now editing a series of short essays on China and the Nobel Prize. Mo Yan’s 2012 win, in addition to dramatically increased global interest in his fiction, inspired some readers around the world to try to find out more about Chinese literature in general.* Soon, the 2013 winner will be announced, putting a new author in the limelight and perhaps leading to new or renewed international attention to the literary landscape of his or her nation. Initially, though, there will be a window of time when last year’s and this year’s winner and their respective countries will be compared and contrasted. We see this as a last opportune moment to use Mo Yan’s win to increase awareness of various writers with links to China who have been, could have been, should have been, or might someday be literary laureates. We’re currently editing an essay on Buck, who became a laureate in 1938, and we’ll be grandfathering into the series the interview on Mo Yan I did with Sabina Knight almost a year ago. We won’t be commissioning a piece on Tagore. But as the first Asian writer to win the Nobel Prize (exactly a century ago this year) and someone who met with leading Chinese writers while touring China and giving lectures ten years after becoming a laureate, his name is sure to come up somewhere — certainly, if nowhere else, in the introduction that Megan and I write for the e-book based on the series.

What then of the other tie between Tagore, Buck and Mo? Well, they will all be mentioned in the book I’m currently writing, which will tell the story of both the anti-Christian Boxer Rising and the invasion by armies marching under eight foreign flags that quelled it. Tagore, who followed the events in question closely, was dismayed at the brutality of the foreign invasion of China. Buck was part of a missionary family living in China that fled to escape from the Boxers. And the Boxers figure centrally in a recent Mo Yan novel, Sandalwood Death. At most, in past histories of the Chinese crises of 1900, you will find only one or two of the three authors listed in the index, but all members of the trio will make it into mine.

Of course, this is partly because most previous writers on the topic finished their books before Sandalwood Death had been written, but it also reflects some distinctive if not always unique aspects of my book’s approach. One thing I’m concerned with, for example, is how Chinese events of the time were understood in other parts of the world, including India — enter Tagore. I’m also fascinated by the rich afterlife that China’s 1900 has had in popular media, from early silent movies that included reenactments of Boxer attacks on Christians, to an episode of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” with a scene that takes place in Beijing in 1900, to a fascinating new pair of graphic novels that has just made the YA long list for the National Book Awards.** It is only natural, in light of this interest in fictional representations of the Chinese events of 1900, that I will be finding room in my book to talk about Mo Yan, who along with writing Sandalwood Death has told of growing up in a region where the Boxers had once been active, and as a result hearing stories about the insurgents in his youth. And it also makes it natural for me to discuss Pearl Buck, both as an author who wrote about the Boxers and the foreign invasion, and also as a character in a novel: Anchee Min’s Pearl of China, which includes discussion of her family’s experiences during the Boxer crisis.

It’s possible that some other laureates beyond Tagore, Buck and Mo will end up alluded to or quoted in my book. I still need to check, for example, if Gao Xingjian has ever written about the Boxers. Since I am interested in connections between the international conflicts underway in South Africa and China circa 1900, and since Winston Churchill was an eyewitness to the Boer War, he’s another laureate who may get mentioned. The same goes for Rudyard Kipling, whose Nobel Prize win preceded even that of Tagore, making him the very first laureate with significant ties to Asia. As Robert Bickers, the leading historian of British imperialism in China, has noted, Kipling’s poem “Recessional” meant a great deal to the Britons who were trapped, along with other foreigners, in Beijing’s legation quarter in 1900.

What is certain, as opposed to just possible or likely, is that two writers who have been described by some as having been unfairly passed over for Nobel prizes will make their way into my book. One of these is Mark Twain. A strong critic of imperialism, he wrote that, since the Boxers were just trying to get control of their country, if he had been Chinese, he might well have become one. He also had scathing things to say about the hypocritical way that Westerners, including participants in the often brutal campaigns of revenge that followed the lifting of the siege of the foreign legations, could carry out acts of savagery and say they were justified because “civilization” needed to be protected. The other great author who didn’t win a Nobel who will figure in my book is Lao She, the subject of a forthcoming contribution to Megan’s and my LARB series. How could he not get discussed? The Boxer crisis had a more profound impact on his life than it did on that of any other famous writer. His father was a soldier who was killed during street fighting in the capital. The author, who was born in 1899, was just an infant when that happened, but he remembers growing up hearing his mother tell stories about “foreign devils” who “were more barbaric” that the monsters in “any fairy tale.” Her stories, he claimed, had special power since they were not made up, but were instead “100 per cent factual” tales of events that “directly affected our whole family.”

* For a wonderful example of Mo Yan’s Nobel win, leading a reader to immerse herself in not just his work, but also that of many other Chinese writers, see Anjum Hasan’s “Chinese Whispers: Contemporary Chinese Fiction through an Indian Lens”, which just appeared in The Caravan: A Journal of Politics & Culture.

** The twinned graphic novels, which tell the story of China in 1900 through the eyes of two youths — a boy who became a Boxer (his version of the story is titled Boxers) and a girl who converted to Christianity (her version is title Saints) — are by Gene Luen Yang. Published September 10 by First Second, they are available both separately and as a single volume combined work, titled Boxers & Saints.