Terry Lautz is the author of John Birch: A Life (Oxford, 2016). He is interim director of the East Asian Program at Syracuse University and former vice president of the Luce Foundation.

We’ll get to your fascinating book in a minute, but you’ve spent a long time thinking deeply about U.S.-China relations, both as a scholar and in your capacity until recently as a leading figure in the Luce Foundation, so I want to begin with some general questions relating to the tensions and ties between the two countries. We are at a delicate moment in U.S.-China relations and a tricky point in time when it comes to images that Chinese and Americans have of one another. What strikes you as most interesting and most dangerous about this juncture?

From a U.S. perspective, I think the most interesting development is a growing sense of disappointment, disillusion, and even alarm over China’s current direction. I’m wary of the growing chorus of pundits who say China has made an irreversible choice to reject more liberal policies. From a distance, Westerners tend to view China as a monolith that moves in lockstep on orders from Beijing. China is more like Dr. Doolittle’s pushmi-pullyu, an imaginary animal with two heads and two minds pointing in opposite directions. One is pushing toward openness and reform, while the other is pulling toward control and repression. At this juncture, the second head seems to be winning out, and we should be concerned about a more authoritarian direction under President Xi Jinping. But China is in a state of constant social, economic, and political change.

I think the greatest danger in terms of Sino-American mutual perceptions is the risk of a self-fulfilling prophecy. If both sides perceive the other as an enemy, it increases the possibility that we will actually become enemies. Despite significant mutual interests — ranging from trade and investment to climate change to nuclear proliferation — the relationship is in a downward cycle right now. So it’s more important than ever to stay engaged and try to address the sources of distrust. Americans need to adjust to China’s status as a major world power, and Chinese should understand the hazards of anti-foreign nationalism.

Do you hear echoes of past rhetoric about China in current discussions of the threat that the country poses to the United States?

The idea of China as a threat has been a steady theme in American perceptions, alternating with more positive, often romanticized views. Early on, it was the racist dread of a Yellow Peril. After Mao seized power, it was the specter of a Red Menace. These stereotypes assumed that all Chinese look and act alike. Fortunately, as our two nations have become inter-connected, U.S. public opinion has evolved. Stereotyping still exists, but Americans are mostly worried about practical issues such as the loss of jobs, trade deficits, and cyber attacks as well as China’s impact on the environment and its growing military power.

We hear a lot about China as a threat in the South China Sea. While this is a source of concern, I think it is mainly a test of wills. China is deeply ambivalent when it comes to the U.S. presence in East Asia. On the one hand, many Chinese believe that the United States opposes China’s rise and seeks to undermine its political system through “peaceful evolution.” According to this line of thinking, America’s arms sales to Taiwan are evidence of a U.S. policy to prevent China’s unification. On the other hand, China’s leaders realize that the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the region could lead Japan and South Korea to arm themselves with nuclear weapons. So Beijing resents the United States as a “hegemon” but understands the stability that continued U.S. presence brings to the region.

In terms of the rhetoric coming from the other side of the Pacific relating to pernicious “Western” ideas and values, how concerned are you about official pronouncements in China about the need to be more vigilant in protecting the country from these and about new regulations regarding non-governmental organizations (NGOs), a category that includes civil society groups and apparently also educational institutions with ties to the United States?

The current campaign against so-called Western values is perplexing. At the same time Chinese students are being warned about the risks of glorifying foreigners, they are flocking to Western universities in record numbers. China has become a global power, yet it practices extensive censorship of the internet. Contradictions like these reflect a confusing mixture of confidence and insecurity on the part of China’s leadership. What seems clear is Xi Jinping’s determination to avoid the fate of the former Soviet Union, which means that advocates for constitutional democracy and freedom of speech will not be allowed to challenge Party rule.

The recently announced foreign NGO management law looks like part of a broader movement to control and limit outside influence. International as well as Chinese organizations that support activities such as poverty relief, healthcare, and education should be able to continue their work. But advocates for legal and human rights will face an even more restrictive environment. The silver lining in this dark cloud may be that China’s civil society sector will grow stronger as it becomes more self-sufficient. It is worth noting that China is following others, including Egypt, India, and Russia, in limiting the influence of foreigners.

No one can predict the future, but a couple of things seem clear. First, China is no longer a weak supplicant subject to well-meaning American (or Western) paternalism. And second, there is no viable alternative to Communist Party rule in China for the foreseeable future. This means we have to revisit the longstanding assumption that sooner or later China will follow a liberal, democratic path and become more like us. Whatever the path, history tells us it won’t be a smooth and straight line.

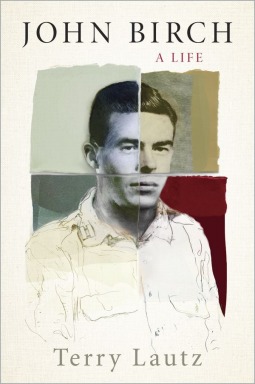

Turning to your book, for Americans, like me, who grew up during the Cold War, the name “John Birch” immediately calls to mind one thing: a staunchly conservative organization. Your biography of the man shows, though, that the chain of associations conjured up by the term “John Birch Society” has little to do with the historical figure. Who exactly was he? And why did you feel that having a background in Chinese studies made you a particularly appropriate person to write his biography?

Like you, I grew up thinking John Birch was a right-wing fanatic, and was quite surprised to discover that he had absolutely nothing to do with naming the John Birch Society. Birch spent five years in China during World War II, first as a Baptist missionary and then as a military intelligence officer, working for Claire Chennault, who commanded the Flying Tigers and then the 14th Air Force. Ten days after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Birch was shot and killed in an altercation with Chinese Communists in North China. It was later claimed that he sacrificed his life to show that the Communists were enemies of the United States, even though they were cooperation with the U.S. against Japan at the time. I argue in the book that Birch had no desire to be a martyr and his name was misappropriated.

I’ve long been interested in U.S. relations with China during the Second World War and the origins of the Cold War in Asia. This started when I lived in Taiwan as a teenager. After college, I served with the U.S. Army in Vietnam and concluded that Americans needed to learn much more about Asia. I was also drawn to the story of Birch as an idealist young man whose life personified the basic American impulses to save, rescue, and defend the Chinese people. Through various twists and turns, he then became a symbol of America’s fear and rejection of China.

The biggest challenge in writing the book was educating myself about the history of the U.S. conservative movement. I wanted to understand why the Birch Society, which is now viewed a predecessor to the Tea Party and even the conspiracy-minded Donald Trump, was popular with many middle-class Americans during the late 1950s and 1960s. I also wanted to know how it became so controversial.