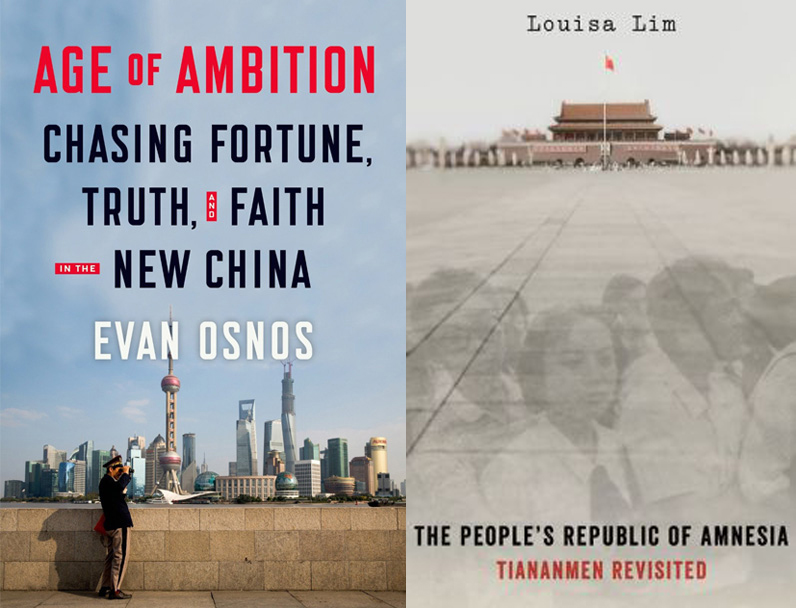

Many twelve-month periods witness the publication of one or two significant books by talented journalists with long experience covering China. 2014 was special, though, due to seeing not just an unusually large number but also a great variety of works of this sort appear. It was the year, for example, of Howard French’s China’s Second Continent, an ethnographically minded work based on interviews conducted with Chinese migrants in Africa, and also of the largely Beijing-set spy thriller Night Heron, by Adam Brookes. These two books have nothing in common save for the fact that both are by authors with a deep understanding of China, derived from their long experience covering the country — in French’s case for the New York Times, in Brookes’s for the BBC. And neither of those two 2014 publications were much like either of the ones flagged in the title of this post, which were part of the same bumper crop of China books. The first of these, by Louisa Lim, offers a detailed look at the legacy and contested memory of 1989’s protests and massacres, while the second, by Evan Osnos, provides a profile-driven survey of the current Chinese political and social scenes.

As regular readers of this blog will know, Lim and Osnos agreed last May to participate in a complexly structured collective post, for which I questioned them and then they questioned one another. Since paperback editions of their books are due out this spring — Amnesia at the start of June, and Ambition two weeks before that — it seemed fitting to email Lim and Osnos to see if they were game to be part of a less complicated sequel that could run as the first post of the season. I promised that this time there would just be a single question to answer, and that they should feel free to respond as briefly or expansively as they wished.

I was pleased when both agreed, even though my emails reached them at busy times. Lim was midway through a semester of teaching at the University of Michigan and getting ready to travel to Chicago for this week’s annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, where she’ll participate in a special panel on protest and dissent on Friday morning. For his part, Osnos, now based in Washington and writing mostly on U.S. politics, was prepping to give a high–profile talk on China at Sidwell Friends — a school with a long tradition of Chinese studies and pupils who include President Obama’s two daughters.

What I asked Lim and Osnos — whose works were both recently shortlisted for a prestigious New York Public Library book prize — was what they thought was most noteworthy about the last year, as far as the themes explored in their books were concerned.

***

Louisa Lim: I have written an epilogue to my paperback edition focusing on Hong Kong’s Umbrella movement, when Hong Kong people occupied some of the city’s most important roads for seventy-nine days, demanding democratic reforms. It was the largest challenge to the Communist party since the protests of 1989, and I write about the similarities — and the considerable differences — between the two movements and Beijing’s response.

Last year was a particularly repressive year in China. One overseas human rights group, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, counted 152 people who had been detained, disappeared or questioned in the run-up to the June 4th anniversary. The reprisals continued when Occupy Hong Kong erupted with 115 mainlanders detained for expressions of support for the Hong Kong protestors. Internet censorship intensified, with censors deleting twice as many posts as they had during the June 4th anniversary. The question remains: why are the authorities so fearful that they deemed it necessary to detain twenty-seven-year old Liu Wei for the act of taking a selfie while making the peace sign in front of Tiananmen gate? Why was factory worker Zhu Tao detained for “creating a disturbance” for posting a picture of himself online wearing black on the anniversary of June 4th?

As I write in my epilogue:

“The message is unmistakeable: June Fourth was forbidden territory, more so in 2014 than ever before. The passage of time has not lessened the Chinese government’s sensitivity towards the events of 1989. On the contrary, it has increased it. As George Orwell wrote in 1984, ‘Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’ Tiananmen was the past, Occupy Central is the present, and to control its future, China’s Communist Party was doing its best to make both disappear.”

Evan Osnos: In the year since Age of Ambition came out, I’ve been struck that an underlying conflict has burst fully into view. For years, those of us who lived in China, or thought about it for a living, had watched as Chinese friends registered growing alarm about corruption. Over dinner at my house, a woman who lives in Guangzhou had complained about having to go to ATMs in the hospital to withdraw stacks of cash with which to tip her mother’s doctor before the surgery. The government used to suppress this kind of discussion because it was unattractive, but today it has taken control of the discussion and amplifies it in a very specific way.

China’s leaders wants to demonstrate that the Party recognizes how severe corruption had become—and is doing something about it. But it’s the latter part that’s less clear. Will an anti-corruption campaign that relies on a kind of investigative fury, rather than on institution building, have a lasting effect? Is the effort to arrest high-ranking corrupt “tigers” actually solving the frustrations with “flies” at the local level? These are questions that confront us more clearly today than a year ago.