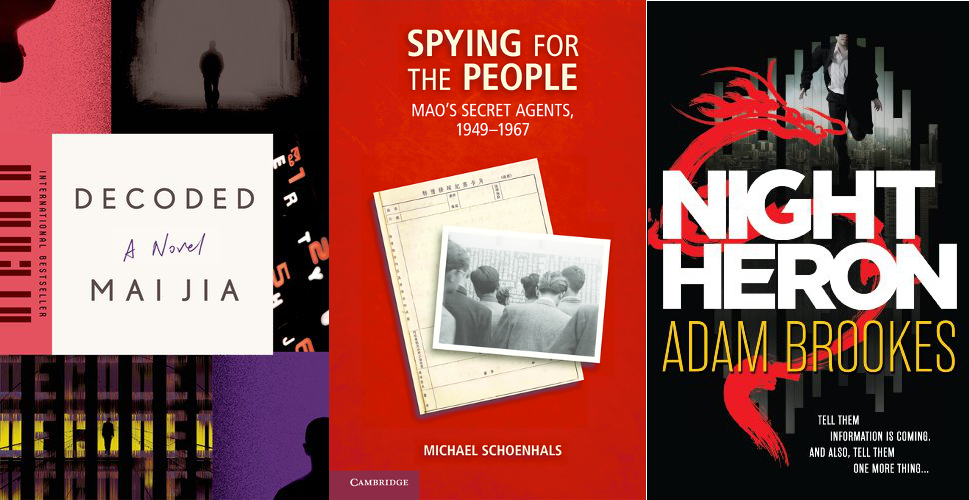

My last post focused on whodunits and true crime books with Chinese settings, but its title, “Noir Visions of China’s Past and Present,” used a capacious term that can encompass other sorts of writings as well. There are, for example, noir novels and noir-infused non-fiction that deal with spies as opposed to private eyes, code making and code breaking rather than police procedures, intelligence gathering drama more than the courtroom sort. And, in fact, when I alluded in that earlier post to China noir titles on the horizon that might be getting attention in the Los Angeles Review of Books soon, I was thinking in part of works by a pair of authors who have more in common with Ludlam and le Carré than Christie and Chandler. One of these is Mai Jia whose Decoded, a bestseller in China, is now out in English in a translation by Olivia Milburn. The other is Adam Brookes, a highly regarded BBC journalist, whose fiction debut, Night Heron, will be published next month. A series of positive reviews have put Decoded near the top of my “to-read” list. Night Heron, meanwhile, is among the favorite titles on my “recently-read” list: I tore through an advance copy, finding its largely Beijing-set tale of secret agents and international intrigue engrossing and compelling. I came away from reading it agreeing with Publisher’s Weekly that Brookes (full disclosure: someone I know and like) is a “thriller writer to watch.”

Of course, while some books can be placed neatly one or the other side of the mysteries-vs-espionage tales divide, others cross or at least blur the boundary. Take the Ellie McEnroe stories by Lisa Brackmann discussed in last week’s post. It’s tempting to categorize their protagonist as a “tough female detective” in the V.I. Warshawski mode, but Rock Paper Tiger and Hour of the Rat include characters involved in shady intelligence operations and McEnroe is sometimes on the run in Bourne-like fashion. And even in the tales of Sherlock Holmes, whose popularity in China was the subject of an earlier contribution to this blog by Edgar-winning true crime writer Paul French, the division between the domains of private eyes and spies was not always absolute. The Conan Doyle character is rightly famous as the archetypal “consulting detective,” but some cases he took up moved into the realm of the guarding and revealing of official secrets, thanks in part to his brother Mycroft’s ties to the British government.

A new window on the link between Holmes and China and between the realms of espionage and Baker Street-style detective work is opened by Spying for the People: Mao’s Secret Agents, 1949-1967, a fascinating book published last year by Cambridge University Press that I just finished reading. The book’s author is Swedish Sinologist Michael Schoenhals, whose previous publications range from Mao’s Last Revolution (an acclaimed history of the Cultural Revolution that he and Roderick MacFarquhar co-wrote) to influential studies of Communist Party rhetoric and terminology (including contributions to the “Indiana East Asian Working Papers on Language and Politics in Modern China” series that I co-edited with Sue Tuohy). In Spying for the People, which focuses on domestic intelligence gathering (as opposed to international espionage) and makes use of an impressively eclectic set of hard to find materials (from discarded diaries bought in flea markets to government reports), he provides a detailed look at how the agents who played such a central role in China’s “dossier dictatorship” of the Mao era were recruited and trained, promoted and purged, thought about and controlled.

Where does Holmes come in? His cameo comes on page 179, in a section devoted to the use those responsible for schooling Chinese agents in “tradecraft” made of various works on the subject produced abroad. After giving a rundown of some contemporary writings on espionage that were translated into Chinese—e.g., “the April 1963 Harper’s Magazine article ‘The Craft of Intelligence’ by the U.S. director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Allen W. Dulles” and, in abridged form, “David Wise and Thomas B. Ross’s 1964 exposé The Invisible Government, described by the CIA’s legal counsel at the time as ‘uncannily accurate’”—Schoenhals notes, on “a lighter note,” that agents were encouraged to read Conan Doyle’s fiction. “In 1961, at a conference on surveillance work in Shanghai,” he writes, “the municipal director of public security was heard observing that ‘whereas we cannot put our faith in Holmes’s repertoire of feudal, bourgeois, and fascist tricks—but must come up with our own proletarian and revolutionary Holmes—some of that old stuff may still prove to be useful here and there.’”

This is a nice light moment indeed in a book on a dark subject, but it is by no means the only place where Schoenhals has some impish fun with his topic. For example, section titles in a chapter on recruitment strategies, which explores different methods used to get people to agree to work as spies, include the following: “The Gradual Pitch: I Thought You’d Never Ask,” “The Hard Pitch: An Offer You Can’t Refuse,” and “The Patriotic Pitch: Your Country Needs You!”

In addition, just after his comments about learning from Holmes, Schoenhals tells an anecdote about a Chinese public security head asking his “officers to learn how to ‘adopt clever disguises and move about observing things incognito’ by emulating Kuang Zhong, the upstanding Suzhou governor of the Ming Dynasty in the Kunqu Opera Fifteen Strings of Cash.” He goes on to note that this same official also “boasted in private” that he had once used skills of this type himself to infiltrate a famous (and infamous) “entertainment complex” and, while incognito, had easily “distinguished the ‘ladyboys’ (yaoguai) from the common prostitutes plying their trade there.” As in many noir novels, there is plenty of room in Spying for the People, a noir-infused work of non-fiction, for discussion of varied sorts of social actors, activities, and settings, and many types of investigations.