By Austin L. Dean

By now you have probably heard of Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce company that had a gargantuan $21 billion initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange in September. You might have seen an interview with Jack Ma, the former English-teacher and CEO of Alibaba, as he made the rounds of the American business media. You might have even read stories about the vast number products for sale of Alibaba’s website: cherries from American farmers, freshly caught oysters from off the coast of New Zealand. Everything, it seems, is available through one of Alibaba’s online marketplaces—one of which, Taobao, was described in detail in Alec Ash’s post for this blog just last week. The company, or at least their public relations materials, claims it is bringing the world to China and China to the world.

But Alibaba is not the only website in China. In fact, it is not necessarily the best place for buying old Chinese books. For the collector, the academic, and the booklover — as Maggie Greene told reader’s of the China Beat, a precursor of sorts to this blog, back in 2011 — there is another web portal with more appeal: Kongfuzi. Named, appropriately, for the early Chinese philosopher Confucius, it is the largest website devoted to old Chinese books in the world. Its closest English-language equivalent is Alibris, a website offering new, used, and rare books along with music and other entertainment products. For everything from volumes that are hundred of years old to academic books published twenty years ago that are now impossible to find on the shelves of most bookstores, Kongfuzi is the place to go.

In fact, Kongfuzi is more than just a site for books; it’s also like an antique market. It has the reputation of being the place to look for all sorts of things that are find to hard elsewhere. Founded in 2002, it is a combination of a marketplace and an auction-house and follows a familiar model. Antique stores, used bookstores, and individual sellers register on the site to list their wares: books, paintings, calligraphy, old coins, and other types of collector’s items. The auctions cater to people who know that they want to buy but also nurtures the urge to buy things you weren’t looking for but suddenly decide you have to have because it is so rare once you see it.

Some of the hottest auctions from the site show just how varied it is: scrolls of calligraphy from the Qing Dynasty, wares from the Han Dynasty and complete sets of hard to find book collections. Of course, as with any online marketplace and with those specializing in antiques in particular, and especially Chinese antiques—a market rife with counterfeits — it is a caveat emptor environment.

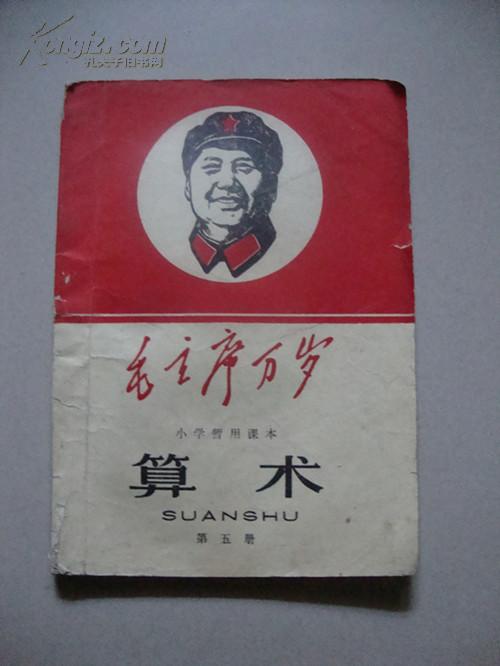

However, the site’s most interesting feature is not as a marketplace for material from the Ming, Qing, and Republican eras but as a repository for the historical memory of more recent Chinese history, particularly the early period the of People’s Republic of China circa 1949 to the to 1976, the year of Mao’s death. Searching Kongfuzi you can find materials that follows a person throughout the course of the Mao years: An elementary school arithmetic primer with a picture of the Chairman on the cover, review books for the college entrance exam, individual registrations sheets for the entrance exam, maps and propaganda poster, pamphlets about how to be a good worker, marriage certificates from the 1960s and a case about a divorce in 1970.

These are all simple materials—not many people are likely on the lookout for arithmetic primers from the 1950s—but, when put together, they form an archive of the recent Chinese past that despite its proximity often feels remote, particularly since China has changed so much. Kongfuzi, then, is a place to buy old books and paintings but also a place to piece together Chinese history.

Just as Kongfuzi serves as a repository of the Chinese past, the various sites of Alibaba serve as a record and a repository of the Chinese present and, searching through the various products, one finds all kinds of products and services needed or wanted in daily life: the mundane, like clothes, shoes, detergent; the immoral, people to do your homework and write college admissions letters on your behalf; the exotic, such as those imported oysters and cherries. The line by economist John Maynard Keyes describing the world one hundred year ago rings true today, with just a bit of technological and geographic transposition: “The Inhabitant of London (or, in this case, Shanghai), could order by telephone (or a smart phone), sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.”

Spending time scrolling through Kongfuzi and Alibaba reveals a lot about Chinese history. In fact, there are probably no two better sites for understanding just how much China has changed during the past 65 years: from math primers featuring Chairman Mao to advertisements for review classes to help Chinese students get into American colleges.