By James Carter

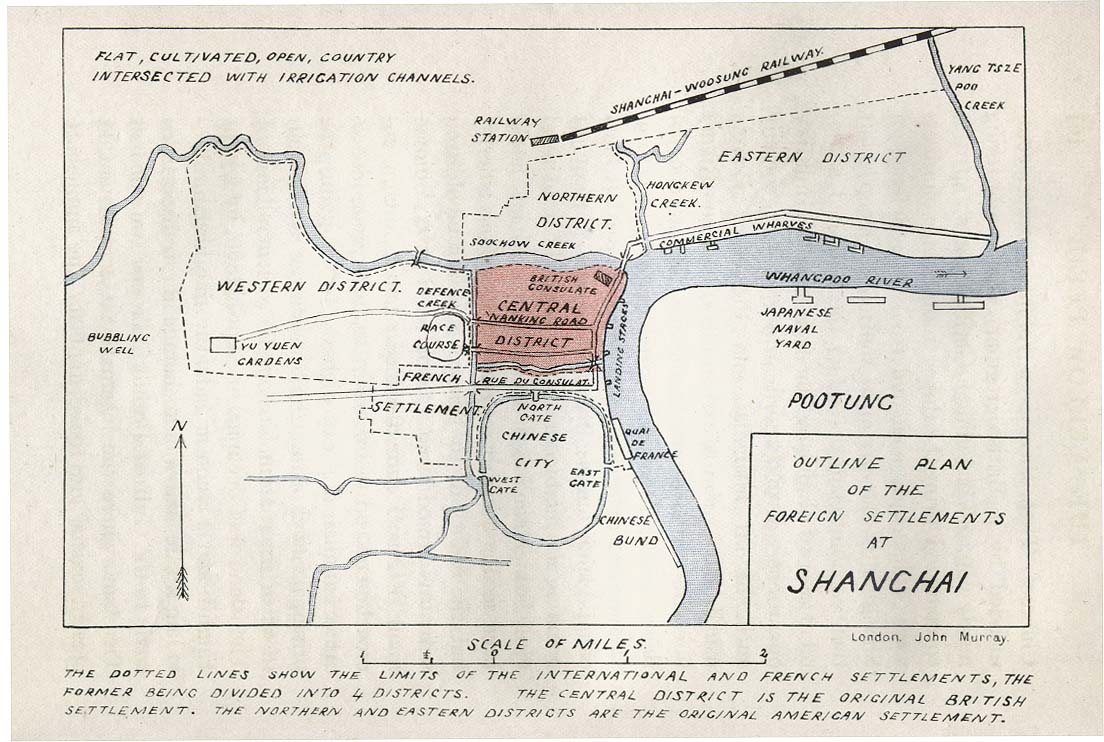

With Fall Break relieving me from teaching for a few days, I recently spent a week in Shanghai researching a new book that uses the events of a single day at the local horse-races to explore a variety of questions about China’s 20th-century history. I’m interested in that particular place at that particular time (late in 1941) in part because I like projects that draw attention to how porous seemingly basic boundaries separating cultural groups and periods can be. Shanghai spent a century (1843-1943) subdivided into Chinese-run districts and two foreign-run enclaves, a French Concession and an International Settlement, which were all interconnected even though each was governed differently. The racetrack, for example, was in the International Settlement, which was usually dominated by British interests, but people from all parts of the city and of all nationalities came to bet on the ponies.

Why is 1941 special? Because when writing about Chinese history, 1937 — when Japan invaded North China, occupied many coastal cities, and carried out the brutal Rape of Nanjing — is usually regarded as the start of “the war.” Yet, in Shanghai, while the Japanese took over the Chinese-run parts of the city that year, most Western nations remained neutral in the Pacific theater until December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong, Singapore, and other centers of Western power in Asia. In the foreign concessions, life went on more or less as usual after 1937, at least for a while. The race that interests me would be the last “championship” one run before Japan took over the International Settlement, but the 20,000 people who went to bet on the horses did not know that: for them, the drama of the day focused on the rivalry between top stables, not geopolitics.

Long-dead horses and jockeys, though, weren’t the only racers on my mind during this trip, as it came just five weeks before I was set to run my first marathon back home. That meant I wanted to log not just time in the archives but also some miles — ideally a lot of them, even if doing so would require breathing air much smoggier than what I am used to in Philadelphia.

Undaunted by PM 2.5 warnings (nothing Beijingers would fear, mind you), encouraged by jetlag, I set out early most mornings on the pedestrian walkway that runs 1.5 miles along the banks of the Huangpu River. The view was spectacular as the sun came up through the skyscrapers of Pudong, illuminating now-clichéd architectural contrasts: to the West, China’s past (the 19th- and 20th-century buildings of the Bund); across the river to the East, its future (the towering glass skyscrapers, including the world’s second-tallest, nearing completion).

So compelling is the view that it makes the clichés easy to accept at face value. Even the clock on the Customs House, hammering out “The East is Red” (Mao Zedong’s personal anthem) for the tourists seated at Starbucks or Subway, seems contrived to reinforce ironic observations that oversimplify just how it is that, Kipling notwithstanding, East and West meet in Shanghai.

Fortunately, a handful of virtual running companions complicated and illuminated the interactions between China and the West over the past several centuries. Podcasts have long been one of my favorite information sources, and listening to them makes commutes and runs both productive and entertaining. For those with an interest in China, the sources are many. Three reliable standards helped me pass the miles and at the same time situate my research, so I left Shanghai with both a productive research trip and about 30 miles under my belt. I’d recommend all three without reservation for anyone interested in deepening their understanding of China.

The most provocative of my choices was Carla Nappi’s interview with Oxford historian Henrietta Harrison, talking about her recent book, The Missionary’s Curse. Harrison is one of the leading voices in the field, and this book deftly undermines many of the clichés that make the Bund waterfront so appealing. She writes here about Shanxi, traditionally regarded as one of China’s poorest, most isolated provinces. Running past the European icons of Shanghai’s gilded age, like HSBC, AIA, and the Peace Hotel, it was easy to think that relations between China and Europe were best observed here. What could show this blending better than the Chinese-style roof atop the Art Deco Bank of China, for instance? Yet Harrison’s study — subtitled Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village — demonstrates that the mutual influence of Chinese and Western institutions and ideas has gone on for longer, at a much subtler and grassroots level, than is evident in the Art Deco monuments along the Bund.

Just as much as Harrison’s scholarship, this interview showcased the fine work being done in the New Books in East Asian Studies series. Nappi, an accomplished historian in her own right (author of The Monkey and the Inkpot: Natural History and Its Transformations in Early Modern China), posts interviews every week or two and shows a remarkable familiarity with her subjects, as well as an engaging interview style. Most interviews run more than an hour, allowing for in-depth and detailed discussions of recent books on China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. The New Books Network also has counterparts of other sub-areas, including History, Critical Theory, Philosophy, and dozens more. If you want a book review mobile and thorough, this is a site for you.

Nappi’s interviews feel like joining two very smart people for a cup of tea (and at least one recent interview actually was done over tea, though more commonly they take place over Skype). No less smart, Kaiser Kuo and Jeremy Goldkorn’s Sinica Podcast is more like gathering for a pint (or two) with the most well-informed expats in China. Readers with more interest in news stories than academic debates might find this the best place to start. Sinica — now archived at the Asia Society’s ChinaFile site — bills itself as a weekly discussion of current events in China, yet that is only part of its portfolio. Kaiser and Jeremy (forgive the familiarity, but the podcast frowns on pretension in all its forms) gather together journalists, authors, academics, and businesspeople, either based in Beijing or passing through. Top China-based journalists, including The Economist’s Gady Epstein, The New York Times’ Ed Wong (and in back episodes, Mary Kay Magistad of PRI and Evan Osnos of The New Yorker, both now relocated to the USA) are regular guests, making the podcast a source of insight and reportage, not just rehashing of yesterday’s headlines.

Keeping with the Sino-Western theme, the installment I listened to during one morning’s run featured author and diver Steven Schwankert, whose new book Poseidon details the story of HMS Poseidon, a British submarine that was lost in 1931, but secretly salvaged in 1972 by the Chinese navy. Schwankert’s insights on China and the West, like Harrison’s, complicate what we think we know. For me, the idea that a British submarine could be salvaged in the 1970s without any British knowledge whatsoever was surprising. Just as surprising was the fact that the submarine’s fate was revealed not through espionage or high-level diplomacy, but through the pages of a Chinese popular magazine that Schwankert came across while searching for information about the sub’s location for a possible dive: no such dive was possible, since the vessel was raised from the bottom 40 years ago!

Last up was the China History Podcast, which businessman Laszlo Montgomery has researched, produced, and presented for nearly four years. Its somewhat haphazard approach to several millennia of China’s history make for entertaining and unpredictable — but always responsible — glimpses into China’s past. My accompaniment on the Bund adhered to the theme of the week, detailing the life of Hong Kong shipping magnate Y.K. Pao, who counted Ronald Reagan, Deng Xiaoping, and other leaders — West and East — among his friends.

So, about five hours of running between the clichés of Shanghai’s waterfront provided not just fine views, but also fresh understanding of the current state of scholarship and writing about China’s relationship with the West. I also renewed my appreciation for the range of new sources, and new formats, available for today’s China watchers, and deeply grateful to the people who provide these (free!) services, strictly as volunteers. And of course there are lots more podcasts too: one recent addition is The China Hang-up, from the Economic Observer, that follows the Sinica model, taking on current issues in a group discussion format, with call-ins! Podcasts have now matured to the point that there is a “new generation” to challenge the establishment.”

Laszlo Montgomery, Carla Nappi, Jeremy Goldkorn, and Kaiser Kuo — as well as their guests — are crossing another boundary that has never been as solid as some would believe. The lines separating journalism, scholarship, punditry, and analysis are blurred on the Internet as never before. While some fret (with cause) about the degradation of standards that accompany the rise of citizen-journalism and open-source scholarship, the voices on these podcasts show that quality analysis and entertainment is now available on a scale never before seen.