When this post goes live on November 5, I will have just arrived in Hong Kong. I’m heading there in part to give a pair of talks at a university, but more important than that is my desire to see for myself how the city, which has changed so profoundly since I first visited it in 1987, has been transformed by the recent wave of protests. My trip is linked to an experimental course that I’m teaching at UC Irvine. It’s titled “Global Crises” and has included presentations by various regional specialists. Some of these guest speakers have come across campus to give presentations, while others have visited the class long-distance via Skype. While in Hong Kong, I will take my own turn as one of those guests from afar. Joining me in that Skyped-in session will be a Hong Kong-based journalist, a Hong Kong-based academic, and a visiting researcher from the United States, all of whom have been tracking closely the events unfolding on the city’s streets.

The Hong Kong movement I hope to soon know much more about has been nothing if not an eclectic, creative, and cosmopolitan one. Its key symbols include yellow ribbons, umbrellas, and banners, the most famous of which was emblazoned with characters describing a desire for real elections that hung from a leonine rock face above the territory that is an icon of local identity and pride. Its anthems and sing-alongs include everything from John Lennon’s “Imagine,” to a rousing Cantonese pop ballad, to a tune from the Broadway show Les Miserables, to “Raise Your Umbrella,” a song written specifically for the movement. Its main call has been for more democratic methods to be used in selecting the territory’s top official in the future, but it’s a movement whose participants have had many and mixed concerns, inspired to act in some cases by worries about economic issues, such as the widening gap between Hong Kong’s superrich and everyone else. It’s the latest in a series of movements whose overarching goal has been in part simply to ensure that Hong Kong remains less shaped by authoritarian strictures than nearby mainland cities, and is able to retain its sense of distinctiveness and things such as a more developed rule of law that go along with that.

To prepare to make the most of my few days in Hong Kong, I’ve done my homework. I began with immersing myself in the journalistic and social media coverage of current events. I’ve watched YouTube videos and checked out webcams trained on protest sites; I’ve figured out which people using Twitter can be relied upon to provide the best comments, links, and images, and looked at countless photographs posted online, showing everything from students establishing study zones on occupied streets to keep up with their homework, to shots of reimagined struggles between protesters and police made of Lego figures, to people of different social backgrounds wearing goggles to protect their eyes from pepper spray and tear gas, to a local teacher reading aloud from a children’s book featuring allegorical animals dealing with the movement. I’ve also been talking to people I know who have spent time in the city to help me place current events into context.

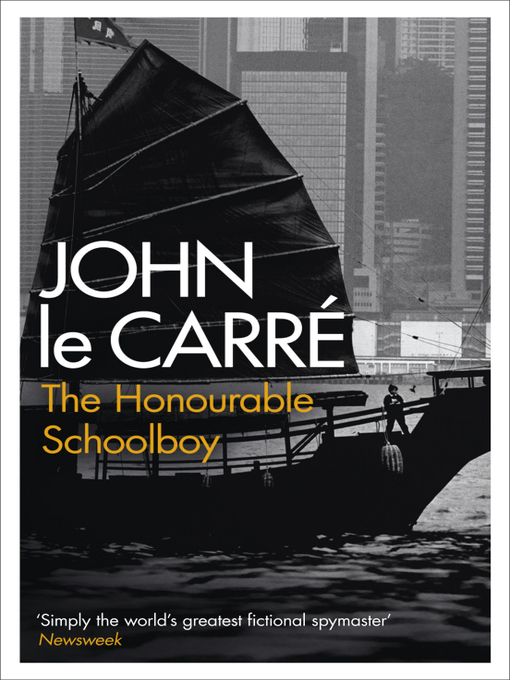

Hong Kong has been so much at the front of my mind that it has even shaped my choices of fiction to read for relaxation. Last summer, I discovered — coming very late indeed to this literary party! — the pleasures of John le Carré spy novels, and I had a vague memory of hearing from someone that he had done a book set in Hong Kong. A quick venture online confirmed that this was indeed the case, and within a few minutes I’d downloaded The Honourable Schoolboy onto my Kindle. I figured that reading it would be enjoyable; would help me expand my sense of Hong Kong’s history, since it was set in the 1970s, well before my first visit there, and drew on research trips to the city the author had made; and yet would be so far removed from contemporary political issues that burying myself in it could still count as a form of escapism. My first two expectations were definitely confirmed, but as for the third… well, true enough when it came to the fictional parts of the book, but not for one of the two prefatory notes by the author that came with the edition I bought.

This first of le Carré’s two Forewords, dated 1977, had no particular tie to today’s concerns, but the second, dated more precisely July 1989, is a different story. When the author wrote this, then-recent events in Beijing were very much on his mind, leading him to insert an allusion to “heroic young Chinese men and women” who were slain after they “asked peaceably for… redefinition of their political identity.” There are, as I have written elsewhere, important things that differentiate Hong Kong’s situation in 2014 from the mainland’s in 1989, but there is no question that recent events, as well as the passing of the 25th anniversary of the June 4th Massacre earlier this year, have once again brought to many minds the “young Chinese men and women” whose fate le Carré invoked.

Also of interest, in light of recent discussions of what has happened in Hong Kong, is the final paragraph of that 1989 Foreword. Building on comments he has just made about the fact that his portrayals of Cambodian settings in the novel need to be thought of as evocations of a “vanished” place, irrevocably changed since the time and hence of purely historical interest, le Carré offers these final thoughts on Hong Kong:

“As to Hong Kong — is that all history too? Even as I write, Mrs. Thatcher’s Foreign Secretary is in the Colony, bravely explaining why Britain can do nothing for a people she has dined off for a hundred and fifty years. Only betrayal, it seems, is timeless.”