Back around the turn of the decade, when the “China Beat” was still up and running as a blog, rather than just the Twitter feed it is now, members of the editorial team would periodically offer readers suggestions for last-minute holiday gifts. We focused on books about China, and even compiled two lists of titles in 2008, one that had no special focus and another that just had publications by contributors to the blog. These lists seemed popular, so we thought: why not revive the tradition here? What follows are two suggestions apiece from the two of us and several of our most frequent fellow “China Bloggers” (sadly, not nearly as nifty a nickname as “China Beatniks” was back in the day). We asked for two titles from each person, making clear that one or both could have only a loose tie to China or perhaps no tie at all.

— Maura Elizabeth Cunningham and Jeff Wasserstrom

Alec Ash:

My first selection is The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin. This Chinese science fiction bestseller bucked the trend of declining book readership when it came out in 2008 to critical and popular success. It’s the first in a trilogy, just released in English with parts two and three to follow soon. The story opens during the Cultural Revolution, with astrophysicist Ye Wenjie out of political favor but offered a reprieve to work in a mysterious cordoned-off satellite dish base called Radar Hill. It turns out they’re sending signals out into space. They get an answer.

It’s a good read in its own right, and science fiction can be a fascinating window into modern China. Whereas contemporary Chinese literature often feels toothless to convey realities about China, sci fi fills the breach because of less stringent censorship for a more roundabout form, but also because some of those realities in a country that has squeezed so much change into just a few decades can frankly seem a little fantastical. Another good read (this one banned in mainland China) is The Fat Years by Chan Koonchung. Plenty to dig your teeth into, for both sci fi geeks and China watchers.

Maura Elizabeth Cunningham:

Back in 2012, I was working at the online magazine ChinaFile and copy edited two excellent travelogues by journalist Michael Meyer (here and here). Meyer told us that the pieces were excerpts from the book he was working on at the time, and so for the past two years I’ve been eagerly anticipating the day when I would get to sit down and read the whole thing. In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China won’t be out in time to leave a copy under the Christmas tree, but I’d highly recommend giving that special someone the gift of a pre-order. I just finished reading an advance copy of the book and decided that it was absolutely worth the wait. (If your gift recipient hasn’t yet read Meyer’s first book, The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed, you might tuck that pre-order slip for In Manchuria inside a copy.)

Another book I tore through in 2014 was Night Heron, the debut spy novel by former China-based BBC journalist Adam Brookes (reviewed for the LARB by Paul French). Night Heron takes old tales of Cold War espionage and updates them for the 21st century, in addition to delivering a nicely observed account of life in China. I’m not really much of a spy novel reader, but I’m already looking forward to the second volume in Brookes’s Night Heron trilogy.

Austin L. Dean:

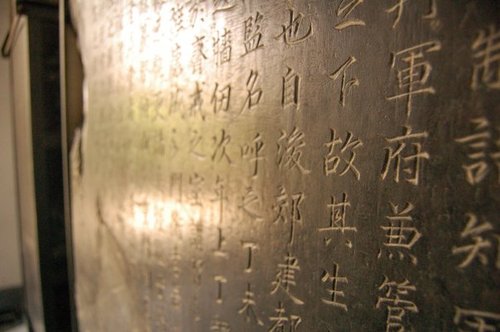

If December makes us reflect on the year that was, a trip to a museum makes us reflect on a much longer time period. In Exhibiting the Past: Historical Memory and the Politics of Museums in Postsocialist China, Kirk Denton, Professor at Ohio State University, visits the plethora of museums that have emerged in China during the last several decades and considers the interpretations of Chinese history they present. Combining the images of a coffee-table book with sharp analysis, Denton examines what exactly museums of modern literature, of ethnography, and of urban planning are trying to say.

Despite the explosion of museums in China, there isn’t likely to be one devoted to the history of golf anytime soon. As Dan Washburn explains in The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream, no sport in China is quite so politically sensitive as hitting the links. The country club activity and communism are hardly natural allies, but they find themselves in an uneasy relationship in contemporary China. In both books, no matter if you are in the museum or on the golf course, the contradictions, changes and tensions in China are on full display.

Paul French:

Everyone has an e-reader now, so two virtual recommendations. Taiwan’s Camphor Press has been reissuing some great China classics as e-books. Peking Dust, Ellen La Motte’s largely forgotten memoir of World War One-era Beijing, is both worth discovering and timely as this is the Christmas, a century ago, that the war wasn’t over by! Camphor also have excellent e-book reissues of classics from Carl Crow and Somerset Maugham. Also, Lao She’s Mr. Ma and Son is now a Penguin Modern Classics e-book. His keenly observed, and often very funny, novel of 1920s London life is a wry take on East-West relations and should provoke a chuckle over the sherry trifle.

Tong Lam:

The London-based Polish writer Agata Pyzik’s Poor but Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West is a highly enjoyable book on pop culture, art, and society in post-1989 Europe. Instead of reinforcing the notion that the collapse of the Berlin Wall signals the end-of-history, Pyzik delves into a wide range of topics in order to reassess the former East. In a broader sense, this book is a critical reflection on the rise of neoliberalism, and what it means to be living in the post-1989 Europe where divisions and nostalgia abound. For readers who are interested in China, thinking about post-1989 China via post-1989 Europe can be a very productive and rewarding intellectual detour, and Poor but Sexy is definitely a good place to start.

A meditation on post-1989 China would perhaps conjure up endless dystopian scenes caused by China’s breakneck urban transformation in the recent decades. For those who are interested in photograph books, Peter Bialobrzeski’s new book, Nail Houses or the Destruction of Lower Shanghai, is a must-have. Urban demolition in Chinese cities is certainly not a new photographic genre, and the book’s one-page introduction does not do justice to these complex issues. But Bialobrzeski, a professor of photography from Germany, is a master of turning night images into surreal and dreamy landscapes. The very unusual layout and paper quality of the final product will also make this stand out as a unique gift.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom:

If you are trying to find the perfect gift for someone who likes striking visual imagery and dystopian fiction, you might consider Chinese historian and globally minded photographer Tong Lam’s Abandoned Futures: A Journey to the Post-Human World. Chockfull of powerful shots of industrial and post-industrial ruins found everywhere from North America and Europe to China, it would fit nicely on any bookshelf right between Greg Girard’s Phantom Shanghai and Mike Davis’s City of Quartz.

My second last minute gift idea is Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation, a deeply informed yet sometimes wickedly funny travelogue-meets-state-of-the-country account by journalist and epidemiologist Elizabeth Pisani. The conceit behind it is a bit reminiscent of China Road, but the author’s writing has a gonzo edge to it that makes her a very different virtual traveling companion than the amiable Rob Gifford. The book is, quite simply, a hoot, which is also filled with information relating to and portraits of memorable people living in a complex nation about which Americans know too little. (China-related trivia bonus: Pisani’s has spent much more time in Southeast than East Asia, but before being trained in the spread of diseases, she studied classical Chinese, and, as regular readers of Granta know, she was an eyewitness to the June 4th Massacre.)