It has now been about half a year since Maura Cunningham started a new position with the Association for Asian Studies and switched from being a co-editor of to an occasional contributor to this blog, so this seemed a good time to check in with her about her new job. It is also an apt moment to check in with her about her activities as a writer, since she has an article in the latest issue of the World Policy Journal.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: Before we get to your new job with AAS, can you tell this blog’s readers a bit about the impressive piece you wrote for the World Policy Journal? I’ve read it but I’m assuming most of them won’t have yet, so just fill them in on what it deals with and what you most want readers to take away from it?

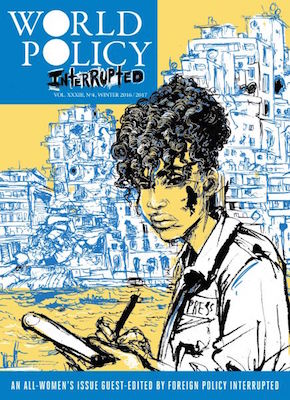

MAURA ELIZABETH CUNNINGHAM: The essay I wrote for World Policy Journal’s all-female-contributor “Interrupted” issue is called “Good Girls Revolt: The future of feminism in China” and is my attempt to consider the past, present, and future prospects of feminism in China in 3,000 or so words. It grew out of an idea that I’ve been thinking over ever since the “Feminist Five” case back in 2015: that although feminist activists like those women attract attention and scare the Chinese leadership, with its paranoia about maintaining social stability, they’re too outrageous to gain a large following among Chinese women. They’re not going to lead a large-scale feminist revolution of the type we associate with Gloria Steinem and her counterparts here in the States. But since my first time in China in 2005, I have seen a shift in the way that some Chinese women — specifically educated urban women — approach the world and articulate their place in it. There’s more discussion about gender equality, more resistance to hierarchies and patriarchies (including the Chinese Communist Party leadership, the ultimate #allmalepanel), and a few attempts at using the legal system to fight against practices like employment discrimination. If I had to guess, I would say that the biggest future changes in gender equality won’t come from women who want to upend societal norms altogether, but those who fight small, personal battles to participate in education, work, marriage, reproduction, etc. on a more equal basis.

World Policy Journal doesn’t include footnotes on its articles, so what are some of the works that you drew on in writing this essay — or just think that people wanting to know more about feminism in China should read?

Leta Hong Fincher’s Leftover Women is certainly the place to start for people interested in learning about gender relations in contemporary China. She’s working on a second book about Chinese feminism today that I’m looking forward to seeing. For those who are interested in women’s history, two books by UC Santa Cruz’s Gail Hershatter are absolutely essential reading: Women in China’s Long Twentieth Century and The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past. And University of Michigan professor Wang Zheng recently published a new book on women in Mao’s China, Finding Women in the State, that I haven’t had a chance to read yet but which looks like important new research, based on the excerpt available online.

What exactly is your position at the AAS and what types of things do you work on there?

I’m the Digital Media Manager, which is a newly created position at AAS, and most of my job falls into two areas. First, I do all the association’s social media, so I’m the woman behind the curtain of our Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram accounts (follow us!). Second, I’ll be the editor of a new blog that will offer commentary and analysis about Asia, as well as news for and about AAS members; that site will (fingers crossed) debut in the next couple of months. In the non-digital realm, I’m also starting to develop some professionalization activities for AAS members. The first one of those will be a special roundtable on non-academic careers for Asianists that will be held at our annual conference in Toronto this March.

When you get time to write, what are you working on?

So many things …! I’ve been keeping a personal blog, “The Wandering Life,” since 2011 and try to post there at least a few times a month. I write freelance articles and essays for a variety of publications. I have a stack of books that I want to review and would like to make inroads on that in 2017 (or at least keep the stack from growing any larger).

But the most important items on my to-do list right now are two book projects. The first is one you know very well, since we’re co-authors; that’s the third edition of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know and will be done as soon as we figure out how to revise that pesky closing chapter on “The Future.” The second project is a graphic history about the life and work of Chinese cartoonist Zhang Leping, which I’m producing in collaboration with artist Liz Clarke for a series of world history textbooks published by Oxford University Press that began with the award-winning Abina and the Important Men. I’ve been working on that manuscript off and on for a couple of years — nobody ever taught me how to write a comic book in graduate school, and it’s been far more difficult than I anticipated! — and have promised my very patient editor that this is the year it gets done.

As a final question, is there any podcast you’ve heard, blog post you’ve read, or Twitter feed you’ve begun to follow lately that made a special impression on you and you want to bring to the attention of our readers?

I’m going to recommend Tricia Wang’s Instagram feed, which will be of interest both to China hands and to academics looking for new ways to share their research (as well as anyone who likes Swedish food, one of her passions that has nothing to do with China). Tricia did a PhD in Sociology at UC San Diego and now works as a “global tech ethnographer,” making regular trips to China. When she’s out in the field doing research, as she has been during the last few weeks, she posts “live field notes” on Instagram — photos with a paragraph or two of description and analysis. Not only do I enjoy her posts because they help me stay in touch with China when I’m not there, I think Tricia has found the perfect medium to disseminate quick notes and impressions from the field in real-time. Her live field notes also show what’s possible when you look beyond the celebrities and lifestyle brand promotions to take Instagram seriously as a platform for discussion and collaboration.