By James Carter

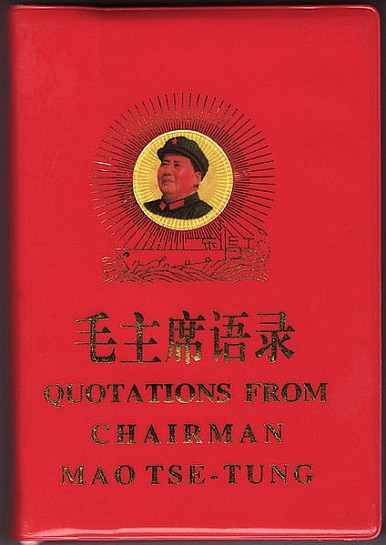

The Grolier Club, sitting today in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the United States, just around the corner from Park Avenue in Manhattan, was established in 1884 “to foster the study, collecting, and appreciation of books and works on paper.” One of the club’s tenets is that it embraces the power of the book, and rejects the notion that the future of the printed page is jeopardized by new technology or social convention. In keeping with that spirit, the current show celebrates one of the most powerful uses of the printed page in recent history, Mao’s “Little Red Book,” a work officially titled Quotations From Chairman Mao (毛主席语). This is the book that launched the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and took Mao’s cult of personality to unprecedented heights. The Grolier Club exhibit devoted to it — “Quotations From Chairman Mao: 50th Anniversary Exhibition, 1964-2014. From the Collection of Justin G. Schiller” — runs until January 10, 2015.

There’s an irony to the fact that the very first page of the canonical collection of quotes by the Chairman is an excerpt from a 1948 speech, in which Mao stresses that without the leadership of the Communist Party “it is impossible to lead the working class and the broad masses of the people in defeating imperialism and its running dogs.” If those “running dogs” he had in mind have a native habitat, it would be Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The exhibition may be devoted to one of the most recognized icons of Communism, but it stands in a part of New York City dominated by sacred names of American capitalism: Park Avenue, Fifth Avenue, Trump Tower, Bloomingdale’s, Madison Avenue. This placement might seem appropriate, given China’s current embrace of state capitalism, but the show is a chance to see some remarkable artifacts from a different time in Chinese history, when leaders in Beijing promised to lead a revolution of proletarian struggle.

When the first editions of the text came out in 1964, they played a central role in Mao’s rehabilitation after the disastrous Great Leap Forward and accompanying famine. Promoted to a figurehead position while Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai navigated China on a much more moderate path forward, Mao fumed at being cast aside and at the “capitalist road” his successors followed. Mao rebuilt his powerbase through the army with the help of Defense Minister Lin Biao. Little Red Books were distributed to every soldier in the People’s Liberation Army. The sheer quantity of Mao’s words was overwhelming and immediate: 720 million copies of the book were published within four years of the first edition.

The Grolier Club exhibition features more than 40 editions of the book, including the rare first edition, from the collection of Justin G. Schiller, an antiquarian bookseller and collector, who became fascinated by the red book on a 1993 trip to China. The exhibition fills just one room in the beautifully appointed second floor of the Grolier Club, but it shows both the scope of the Maoist propaganda machine and its idiosyncratic nature. It’s hard to imagine, in today’s era of standardization, the many varieties and provenances of the book’s many editions, some printed by party schools, military bases, and political committees. Accompanying the books is an array of artifacts illustrating just how broadly and deeply the cult of Mao penetrated Chinese society: sheet music, wall hangings, mirrors, alarm clocks, and rubber Red Guard dolls, all celebrating — sometimes revering — the image and words of Chairman Mao.

By the time Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, the little book of aphorisms was in the hands of millions of Red Guards and other Mao supporters. The first edition of the book was actually white with red letters, and some early editions were different shades of blue, but by the time it went into wide distribution the familiar red vinyl cover had become standard. The name “little red book,” based simply on the book’s appearance, was first applied by foreign observers, and has never been used in Chinese (though the nickname “treasured red book” was adopted, back-translated from English).

Fueled by Quotations, the Cult of Mao transformed China for more than a decade. The Cultural Revolution shattered the educational system and the economy, making ideology paramount. But the book’s effects extended far beyond China. That the Red Book owed its popular name to foreign observers hints at the volume’s global impact. By 1967, copies could be found in bookstores around the world, including the United States, where it was issued as a Bantam paperback. Beijing Foreign Languages Press issued official translations into 50 languages, and there were unofficial versions as well. From Berkeley to Paris to Rome, the Little Red Book became a symbol of anti-establishment left-wing politics. In other settings, like Peru and Tanzania, the Red Book became a central text for revolutionary movements.

The worldwide influence of Mao’s quotations is also at the center of Alexander C. Cook’s recently published edited volume, Mao’s Little Red Book: A Global History, which was mentioned in passing in an earlier contribution to this blog just before it was published. With contributions from scholars in fields ranging from sociology (e.g., Guobin Yang), to history (e.g., Elizabeth McGuire), to literature (e.g., Andrew F. Jones), Cook’s volume follows the Red Book around the world, assessing its impact in Europe (ironically, it achieved cult status in Western European democracies, while it was strictly regulated in Soviet client states), Africa, South America, and Asia. It is perhaps the final irony that while, abroad, the Little Red Book came to symbolize dissent and resistance to authority, in China its goal was to enforce uniformity, and for a time it was so successful that failure to carry the book in the proper circumstance could have serious political consequences.

The Grolier Club’s exhibition reminds us of the power the book had to mobilize a nation at one specific moment in the past, while also offering curious testament to that same small work’s ability to capture the imagination of many living far beyond China’s borders. And isn’t this a particularly apt moment to revisit both the domestic and international impact of the Little Red Book? For not only is much being made in China of the appearance of a new book linked to its latest leader, Xi Jinping, but according to recent news reports it is also making its presence felt in at least one important American corporate headquarters. Just as no history of Mao’s “Little Red Book” is complete without acknowledging its popularity from Paris to Peru, as Cook’s impressive edited collection reminds us, if Xi’s The Governance of China should ever be deemed worthy of an exhibit, surely the curators will need to make space for a photograph of the work being displayed on Mark Zuckerberg’s desk — at a time when that new media maven’s best known product was still banned in Beijing.