There’s been a lot of commentary lately about the challenge that Disney faces marketing the new Star Wars film in China, due to comparative lack of familiarity there with the story and characters. When the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter films premiered on the mainland, things were very different, since they began appearing at a time when Chinese and Western popular culture were increasingly entwined. They also included characters from books that many Chinese had read in translation. By contrast, the Star Wars films do not ride the coattails of books that are well known in China, and the previous movies in the series have only rarely made it into Chinese mainland theaters. When the first Star Wars movie came out in 1977, it was not shown on the mainland for years. This was hardly surprising, given how cut off from the flow of Western popular culture China was throughout the Mao years, and for a decade or so after that period ended. Mao may have already been dead when American viewers first met Leia, Luke and Han Solo, but China was still, “for all intents and purposes,” as Julie Makinen put in a recent Los Angeles Times article on the topic, “in a different universe.”

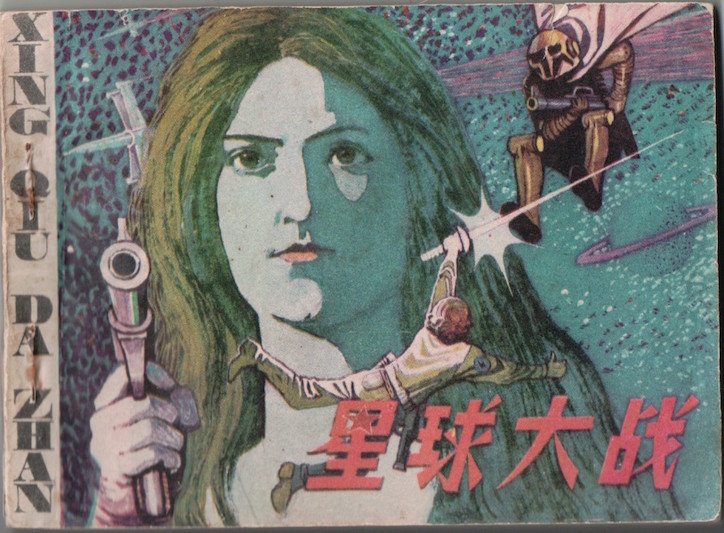

And yet…there was one curious intersection of the early Lucas and early post-Mao universes back in 1980 that historian Maggie Greene discovered via, of all things, collecting lianhuanhua, a genre of illustrated story books. She first wrote about her find in 2014, in a piece for her own website titled, naturally, “A Long Time Ago in a China Far, Far Away…” This led to all sorts of websites, such as iO9, and news services including the BBC describing her find, running excerpts from her post, and/or interviewing her. Reminded of this while reading news coverage of the latest Star Wars film opening in China, I persuaded Greene to respond to a few questions.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: Can you describe in a few sentences what you found and how you found it?

MAGGIE GREENE: In the spring of 2011, I was living in Shanghai while researching my dissertation. I always enjoyed hitting the Sunday book fair at the Confucian Temple (Wen Miao 文庙) to see if I could find anything of use to my work on traditional opera in the 1950s and 1960s. Many sellers had heaps of vintage lianhuanhua — “linked picture books,” little comic books, basically — which are generally very cheap ($1 USD or less), so inexpensive and easy to collect. I asked one seller if he had anything related to my research subjects, and he pulled a few out — including this one. It took me a beat to realize what it was: a 1980 lianhuanhua adaptation of Star Wars. It was so incongruous, and the price was right (about 8 RMB), I simply couldn’t leave it behind.

What is your favorite page from the comic? Why?

There are almost too many to mention! Many discussions of the comic have gone to some lengths to show the source material — such as a cameo appearance of the Yamato from the mid-1970s Japanese anime Space Battleship Yamato — for some of the stranger parts. Learning about those has been one of the neatest things of following up on where the post has been linked. But if forced to pick one, I would probably say Darth Vader and the triceratops. Darth Vader’s pose apparently goes back to an illustration by the fantasy and sci-fi artist Frank Frazetta — where the triceratops came from is anyone’s guess.

What is strangest about the way people and objects from the Star Wars universe are presented in this text?

I think what fascinates me most is how many sources the artists drew from. The lianhuanhua may not have been licensed, but this is really creative “bootlegging.” I like to think of it as a visual remix of a wide variety of sources. I’ve seen some references to comic panels being taken from 1940s comic books, which is pretty amazing if you think about it, especially when combined with the diversity of other materials found in the comic.

How would you define the lianhuanhua genre, for those unfamiliar with it?

Lianhuanhua are little books — most are about the size of your hand — that consist of pictures with captions, originally designed for children or less literate adult readers; they originated in the early 20th century. Generally, traditional stories from mythology, operas, novels, and the like were the sources, although after 1949, the Chinese Communist Party also used them to promulgate socialist virtues and political lessons. Many of the ones I own are exquisitely drawn, so while the text is not necessarily very sophisticated, they are beautiful little pieces of popular art in their own right.

Is there anything important you think has been missing from the reporting on The Force Awakens opening in China — other than allusions to this text, if it indeed hasn’t been mentioned (it may have somewhere I haven’t seen)?*

I think many reports have missed the historical background of Hollywood in China. A number of articles I’ve seen refer to this global film market as if it is some new phenomenon. It’s not! During the Republican era (1911-1949), major cities like Shanghai and Tianjin had a robust market for Hollywood films, and not just for Western residents. Major newspapers carried advertisements for scores of American films being screened — many quite current. Flip through popular magazines like Linglong, and you will see photos of Western film stars like Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, and Shirley Temple, stills from contemporaneous Hollywood films, even sheet music for Marx Brothers musicals! Western films were even put in service to domestic issues — I once saw a very late 1936 ad for a Hollywood Western that made clear allusions to the threat of a Japanese invasion. My students are often surprised by how “globalized” the world was “way back then,” since we often treat this as [if] it’s something that only came about in the 1990s or after.

You noted in your post that this kind of thing isn’t your main focus. Is there any link, though, between your Star Wars post and, say, what you do in the classroom?

Well, as a cultural historian, I use a lot of visual sources in my teaching and like meditating more generally on the refashioning and reshaping of culture over time (and this adaptation certainly counts as “refashioning”!).

How about your research and writing?

I do think these seemingly trifling bits of culture can often reveal a lot about society at specific moments; in that vein, I have an article coming out in Cross-Currents this month on mahjong’s changing position from the late 19th century to 1949. My main task at the moment, however, is pretty far removed from the realm of the Force. I’m preparing a manuscript based on my dissertation entitled “The Sound of Ghosts: Cultural Reform and Censorship in the People’s Republic of China.” In it, [I] examine the relationship between intellectuals, artists, and the state in the 1950s and 1960s, largely by tracing debates and policy regarding classical literature on supernatural themes — particularly ghosts. A commenter on the original blog post expressed surprise that a story about “fighting tyranny” would’ve been so casually published in early 1980s PRC — something that didn’t surprise me at all when I thought about it. In a follow-up post, I connected this kind of story and historical moment to the literary products I study — most of which are stories about fighting tyrannical social systems or corrupt and callous government officials. Will Star Wars have the staying power of something like Tang Xianzu’s famous opera The Peony Pavilion (1598)? I guess our descendants will find out!

*Interviewer’s Note: Since conducting this Q&A, I have seen that at least one publication, TimeOut Beijing, has brought Greene’s find into their discussion of the Chinese opening of The Force Awakens— in a piece with some nice illustrations from the original text.