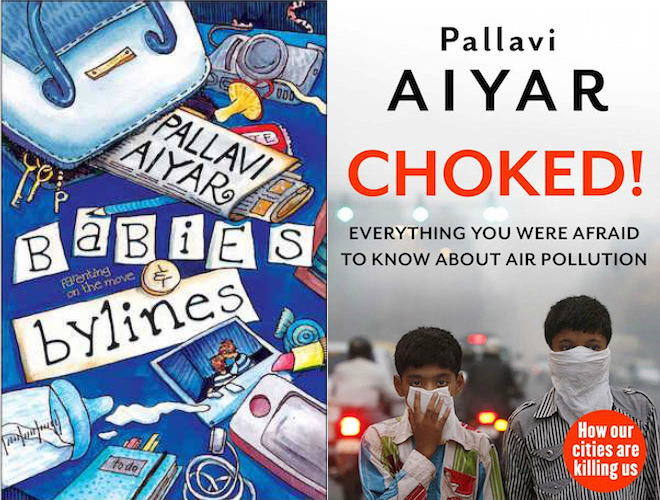

I’ve been a fan of Pallavi Aiyar’s writing since 2008. Back then, she was based in Beijing, reporting for the Hindu as its first Mandarin-speaking correspondent, and had just published her debut book, Smoke and Mirrors: An Experience of China, a prizewinning work that received many positive reviews — including one that I wrote for Foreign Policy. I have continued to read her regularly since she has moved on from China to first Brussels, then Jakarta, and now Tokyo, publishing a novel and several new non-fiction books along the way. I managed to catch up by email recently with the peripatetic and prolific Pallavi, who was incidentally among the first journalists that China Beat interviewed after that precursor to this blog was launched in 2008, and asked her to tell us more about her most recent books, Babies and Bylines and Choked, both 2016 publications.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: Even though Choked and Babies and Bylines are very different kinds of books, there are also clearly some links between them. In this excerpt from Choked, for example, you deal with the implications of not just living in heavily polluted cities as an adult, but doing so as a parent of small children. Can you say a bit more about the similarities, as well as underscoring the contrasts between the projects?

PALLAVI AIYAR: The two books are very different. Babies and Bylines is probably best described as a global parenting memoir, while Choked is more like a piece of long form reportage. I was, however, commissioned to write Choked in part because the commissioning editor knew that I had young children.

Parents tend to be the demographic most concerned about the effects of pollution because children are particularly vulnerable to dirty air. Their respiratory defenses have not reached their full capability and they also breathe in more air per kilo of body weight than adults do. Parents feel guilty wondering if they are harming their children by bringing them up in such polluted environments, and are often desperate for advice on what they can do to mitigate the worst effects of the toxicity. They are therefore an especially receptive audience for a book like Choked.

I am not an environmental or public health expert. I am rather, a mom and a journalist, who has lived in some of the world’s most polluted cities. The publishers wanted this personal flavor to the book. They wanted me to, in a sense, represent parents who are worried and frustrated about the bad air and the effects that it may be having on their family’s health; to ask the right questions and research the solutions on their behalf. So, while in Babies and Bylines my identity as a mother was in the foreground, it also plays a role in Choked.

Another similarity between the books is in the settings. They both move between Beijing, Delhi, Brussels and Jakarta, albeit to different effect.

What stands out for you as the most significant contrast in the way that choking smog in the different cities you’ve lived in is talked about and thought about by long term residents of those places?

What stands out most is not the contrast as much as the similarity in both the trajectory of the fight against air pollution and the general response to the choking smog. In all the badly polluted cities I’ve lived in, of which there are unfortunately many, what is startling is how easily toxic air becomes banal. It is often uncommented upon, even unnoticed. At most, it’s seen as an unmodifiable inconvenience that must be lived with. For many years there is denial of the problem all together. Putrid, sulfurous smog tends blithely to be referred to as “fog” by most citizens until an inflection point is reached, after which there is the opposite reaction of panic and despair.

This is not just the case for Asia’s industrializing megalopolises, but was also true for what are today the rich and relatively clean nations of the West. For example, during the great London smog of December 1952 that is thought to have killed 4,000 people prematurely, the then Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, insisted for days that the smog was merely bad weather.

What is also common to all these cities is that a combination of truly appalling episodes of air pollution, combined with the emergence of a growing, health-conscious middle class and greater international exposure eventually leads to an airwakening of sorts.

Cleaning up the air is not asking for a miracle, it can be done. But it’s a tough process that that requires a combination of political will, citizen awareness, civil society activism, commercial compliance and bureaucratic incentives.

And, as a follow up, what is the most significant contrast about how the Chinese media and Chinese government have dealt with the issue of Beijing’s smog as opposed to the way that Indian media and Indian government have dealt with Delhi’s?

Given that the Chinese media (strongly state controlled) and Indian media (relatively free) landscapes are quite different, the domestic media responded to air pollution in surprisingly similar manner. I think in part this was because in both China and India, the public was inured to what in the West would be considered an array of horrific public heath emergencies. The focus on public discourse in China and India remained on poverty and economic growth. Therefore the environment was not a primary concern for the media until a tipping point was reached. In China this was perhaps the 2008 Olympic Games, whereas in India it was a 2014 WHO report which named New Delhi as the most polluted city in the world.

Although the Chinese media operates within certain constraints, reporting on air pollution has been extensive in recent years. In India, reporting is becoming more intensive but tends to be seasonal. Every winter when weather inversion, the burning of trash and leaves for warmth, and agricultural burning in neighboring states combine to create a visible smog in the capital, reporting on toxic air spikes, but it is then forgotten as the smog recedes and other pressing issues jostle pollution off the headlines

However, what is really interesting is how differently the international media covered air pollution in the two countries. In China air pollution has for long been a primary focus of foreign reporting, whereas even as Delhi’s skies were undeniably toxic there was very little international reporting on pollution in India until fairly recently.

A partial explanation has to do with sympathy for India’s democracy. While foreign correspondents in China saw their role as one of holding an authoritarian, censorship-prone government to account, India was cut greater slack. India was worse off than China on most parameters of human development. Yet, because it is a democracy and therefore assumed to be an ally of western “values,” India was often let off the international hook, on issues that China was skewered for. Air pollution was one case in point.

A clear example of this double standard was in the run up to the Commonwealth Games that Delhi hosted in 2010. These were held only two years after the Olympic Games in Beijing where air pollution had loomed over the international coverage of the event like a smoggy colossus. Yet, in the case of Delhi, although the foreign media did express concerns about the lack of cleanliness at the athlete’s village, corruption and an outbreak of dengue fever, pollution was startlingly missing from their writings

Today, Beijing is synonymous with smog in the global imagination. Contrary to this negative image however, the Chinese authorities have in fact undertaken broad-based and difficult pollution fighting measures that India and other developing countries should study.

According to NASA satellite data, the PM 2.5 levels across India got worse by 13 percent between 2010 and 2015, while China’s steadily improved. Last year was the worst on record for India in terms of particulate pollution and the best in China. PM 2.5 levels across China fell by 17 percent between 2010 and 2015, with quite a dramatic improvement towards 2015 (Beijing saw a 16 percent annual fall in PM 2.5 levels).

It is not some magic wand that has made this possible in China, but the institution of national and regionally coordinated plans including a vast network of air pollution monitoring stations, the installation of pollution abatement equipment on a majority of its power plants, and measures to restrict car ownership in major cities.

For example, China has also developed a network of 1,500 air quality monitoring stations in over 900 cities (India has only 39 such stations covering 23 cities). China is today a world leader in the use and production of wind and solar photovoltaic energy. It produces almost as much energy from wind, sun and water as all of France’s and Germany’s power plants combined.

The share of thermal power plants with basic pollution abatement equipment in China is 95 percent, compared to 10 percent in India. Performance evaluations for local officials in China now factor in environmental measures that they are responsible for. Significantly China has instituted regional air quality regulations to ensure that air pollution is addressed jointly across city and state boundaries.

The Indian government is only just waking up to the crisis. And it’s going to be harder for India than it was for China to tackle dirty air. To begin with, India is less industrialized than China. It is also poorer and will soon be more populous. Consequently its potential for future industrial and vehicular pollution is greater.

Moreover, India’s multi-party, democratic, federal polity is less effective at implementing policy than China’s one-party state. And finally Indians are less public-minded than their Chinese counterparts for complicated historical and cultural reasons including the caste system and the absence of a communist revolution.

Choked has been published in an unusual way. Can you tell us a bit more about that, as well as the best way to get it?

Choked has been published by Juggernaut, a new Indian venture established by Chiki Sarkar, the former publisher of Penguin Random House India. Juggernaut is focused on digital publishing for the mobile market. Choked is available on the Juggernaut app for both IOS and Android, as well as for desktop downloads. International payments should be possible by early December.