“Berlin Notebook: Where Are the Refugees?” is a straightforward journal transcription of my experiences in Berlin during October 2015, a time when the influx of refugees in Germany and the rest of Europe was peaking. I have tried to be as faithful as possible in my reporting of interviews. I have not tried to verify the facts that people presented (when they told them to me); I have tried, rather, to convey the experience of talking with them, what it was like to be there, and to listen, to ask. The form of the interviews may seem to move like the “streaming” metaphor one finds everywhere in use to describe the movement of people across national borders.

This journal transcript will appear here in daily installments. It begins each day with the new installment; to read from the beginning, go to the“Berlin Notebook” archive and scroll down to find the first entry. An ebook version of the complete transcript will be made available soon.

—JW

Friday, 16 October

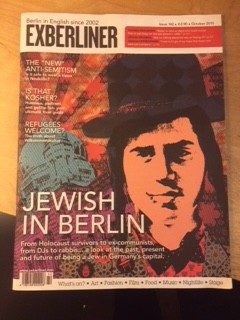

ExBerliner, the expat Anglophone magazine in Berlin since 2002, is devoted this month to two themes: the refugee Willkommenkultur (Welcome Culture), and being “Jewish in Berlin.” Two good things that go together? Jewish “right of return” by those of German descent has been joined in Berlin by a growing influx of Jews from all over the world, most controversially (for Israelis) from Israel. Willkommenkultur is the welcome to refugees demonstrated by members of churches, synagogues, community centers, mobilized neighborhood volunteers, and leftist activists who are stepping in to fill the gaps left by a government bureaucracy staggering under the burden of overwhelming refugee numbers and underwhelming preparation for a crisis that was apparently on its way from the vantage of many months. This staging of welcome is starting to show fault lines in the German people’s attempt to welcome so many desperate and hurting refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, most of whom are practicing Muslims. (Though when I write “practicing Muslims’ the image I call to mind is of the taxi driver I saw in Washington DC on my way to the airport, on his knees on a prayer rug outside the Marriott-Wardman hotel). While the government tries to expedite deportation of Balkan refugees (the Wirtschaftsflüchtlinge, or economic refugees) and constrict the spout of benefits, Berlin scrambles to find empty buildings and plan emergency construction of 30,000 apartments next year. The Federal Office of Migration and Refugees had been consistently low-balling estimates until the Interior Minister dropped the bomb of accurate numbers in August: not 450,000, but twice that number is now expected; it’s likely to be even more. Much more. Hungary has closed its borders; other countries are sure to follow. The grimmest indicator may be that Munich’s decision in September to house refugees in the Dachau concentration camp somehow made sense; the outcry, writes Ben Knight, was not as loud as when Rhine-Westphalia actually put refugees in an outlying concentration camp building only seven months earlier.

Although no state agencies collect data on Jews, the Institute for Jewish Policy Research estimates that Germany has the third largest and fastest growing Jewish population in Western Europe, after France and the UK. There are 120,000 or more Jews in Germany today; according to estimates, half of the them live in Berlin. Before the Holocaust, the ratios were even greater (170,000 of 195,000 German Jews lived in Berlin). The number of anti-Semitic attacks on Jews in Berlin hovers over 200, but parsing that number in terms of German perps or foreigners, explicit acts of anti-Zionism, and acts “against Israel’ (whatever that means), is rather like separating green beans from wax beans. Anti-Semitic crimes are recorded, writes Sara Wilde, by their political motivation. That’s a murky depth to plumb. Jews wearing kippah have been physically and verbally attacked in Neukölln (the Kiez with the thickest Muslim population); but many Jews who do live in the area say they have not experienced anti-Semitism there. Anecdotes and ambiguous stats make it difficult to draw a clear picture. Amongst Germans, feelings about Jews and the nation’s bloodied history is a deep psychic pool, deeper even than ideology, and something akin to the legacy of slavery in the US. The more time I spend here, the more I feel that anti-Semitism is a core problem in the form of a Gordian knot: the right’s hatred of Jews comes together with its hatred of Muslim immigrants, many of whom also themselves hate Jews. The left, with its self-inoculation against Islamophobia as well as against anti-Semitism and anti-facism, finds itself in a double-bind: how can it strike against Sharia and fundamentalist jihad without appearing anti-Muslim? Some are quick to point out that, hey, these guys (Islamic fascists) are not just anti-Semitic, they’re also anti-homosexual, anti-liberal, anti-democratic, anti-tolerant, and not big proponents of women’s rights. How can the left sympathize with the cause of Palestinian self-determination without reanimating anti-Semitic goblins? Can the German left make meaningful distinctions between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism? For many Jews, any criticism of Israeli policies is anti-Semitic; yet the Israeli left has long attempted an intellectual and activist critique of Israel’s reactionary policies (e.g. in the West Bank). You could spend your life sorting it out; and to some extent, to be determined only by your conscience, you should. As always, talking to people is the first step.

Evening, I head out on the metro. The U-bahn to Charlottenburg is a stewing gumbo of disparate language sounds, and every stop introduces new ingredients — to a German base were added mixtures of Slavic, Arabic, and Asian. Some South American guys boarded with a small amp and brass instruments, and started up “When the Saints Go Marching In.” They smiled and sang and pumped the brass valves for a few coins, broke off abruptly at a stop and moved on to another car.

I was on my way to a shabbat dinner with Rabbi Walter Rothschild, Director of the Institut für Jüdische Besserwissenschaft (Institute for Advanced Jewish Studies) and his family, having been invited through an active listserv that started with an ordained feminist rabbi based in Hollywood, Florida — my aunt, Cheryl Weiner. A short walk past the infamous KaDaWe — the “shopping mall of the west” (and in DDR days greatest symbol of its decadence) — past some kosher stores, and I’m facing the apartment building on Passaustrasse. Two guys outside greeted me querulously as I approached the outside board of buzzers. Hallo, they said; it was a question. Hallo, I said, it was my answer. Hallo, they both said again, meaning what the fuck do you want here. Hallo, I said again, meaning none of your fucking business. I moved past them and rang up. (I later learned that they stand outside as guards for a small Sephardic community that convenes in the building).

I entered another spacious old high-ceilinged apartment with overstuffed, bulging, sagging bookcases, packed cd-racks, and a great milky way of everyday objects everywhere, the evidence of a vivacious and busy household. The home gave off a warm vibe boosted by good smells of roasting chicken. Rabbi Walter greeted me—we had never met—and offered me a whiskey. Shabbat hospitality indeed. We were off to a good start. We walked over to a set of old maps hanging on the wall. I began looking at them closely. One was a colored map of the Middle East, the other a city map of Jerusalem. Notice anything, he said. They were both German maps from the early 1940’s. Well, no Israel, obviously, I said, looking at a territory labeled Palestine, that would later become the State of Israel. These are tactical maps of the Wehrmacht (German armed forces), he said, you can see what they were planning for their invasion of the region. He pointed out where the Nazis were imagining train routes and where they would billet the troops in Jerusalem. Scary shit, I said. Yes, indeed, he said, very scary shit. A neighbor found them in his attic, he said, and let me hang them.

Rabbi Walter Rothschild came to Berlin from the UK in 1998 to help revive the Jewish community here. It hasn’t been easy, he tells me, in large part because of the conservative congregations that turn their backs on interfaith marriages and conversions. It’s hard to launch a revival when the values are stubbornly constrictive. The rabbi talked at a quick British clip, with precision, point, humor and wit. Listening to him and surveying his home, I gathered he was a man of appetite, discernment, ironical play, and intellectual and artistic endeavor. I soon found him to be a kind of Renaissance polymath — a poet, musician, scholar, a writer of short stories and memoirist reports from the front lines of rabbinical teaching. As our conversation took various turns, he pulled down notebooks of scholarly studies, volumes published long ago and just released, a cd of original songs with his band, a quarterly he writes and edits devoted to train systems in the Middle East, a satirical cookbook of cannibal recipes, another of anti-moralisms titled Aesop’s Foibles. His grown daughters were equally charming and full of great humor and openness. They welcomed me as an old friend, and were clearly practiced at the Jewish custom of inviting strangers into the home on shabbat. We were joined by a friend, Eva, and her new boyfriend, who, though he spoke little English, communicated engagement with sharp eyes, quick smile, and expressive brows. Dinner was the kind of bubbling conversation and cross table contact of people who delight in each other’s company. As we moved into dessert — Eva’s “cockies” — homemade joke cookies in genitalia shapes — and more wine, tea, whiskey and schnapps (will Berlin ever not be Berlin?) I grabbed my moment to ask the rabbi about the refugee crisis.

Earlier in the evening the rabbi had said to me, rubbing his eyes, I know you’re here to write about the refugees, but I have almost nothing to say about the situation. Now though, with a “cockie” on my plate and a hot cup of tea, I tried a different tact. The good mood of the table and the sociable atmosphere helped. I know, I said, that the refugee crisis is being covered by mainstream media like flies on an open wound. They seem to be doing a good job, I said, I don’t have anything to add to it myself. But I do have a question for you. I waited for the invitation to proceed. So, I said, I’m wondering: What kind of pressure do you think a million Muslims entering Germany is going to put on the Jewish community here, specifically the community in Berlin?

The rabbi began by telling me about getting mugged by three Arab guys outside the Wittenberg U-bahn station, just two blocks from where we sat. Luckily, when a fist smashed his glasses against his face, the shattered lenses did not puncture his eyes. One of the three perps was detained by a security guard; the other two were later picked up by the police. Their heads, said the rabbi, were filled with hateful shit. I’m concerned with who put it there. So, he said, that’s a worry. One big problem, he continued, is that Germany is not really funding efforts for interfaith understanding. It’s difficult, he said, to educate people without adequate funding. The rabbi described efforts he had taken up with priests and imams to go into schools to talk formally with students — but the stipend is so laughably horribly small, that after taxes and paying for one’s own meals over the course of the day, one has only a few dollars left to pocket. It’s not working, he said, we can’t sustain the effort, and there are too few people who can do it to begin with. What’s going to happen to Jews in Berlin, I said. The influx of Muslims is an issue, he said, but it’s not the main issue. In 10 to 15 years, the meaningful presence of Jewish congregations will disappear because the older generation is not bringing up a younger generation. The average age of congregants is 85. There’s no interest in interfaith growth or conversion through marriage. What about all those Israelis coming to Berlin, I said. The Jewish Israelis and the Jewish Americans coming to Berlin, he said, are not coming here to practice Judaism. And even if they have an interest, unless they are registered to pay taxes, they cannot formally join a congregation. Because all these congregations are funded by the state. That’s why they exist, he said, because they get money. And whomever gets the money controls what the community does and how it does it. And in the meantime, they don’t really know what being Jewish is. The whole thing is a Potemkin village, there’s no Judaism there; the continuity has been broken. There was continuity in England, he continued, because German Jewish refugees went to the UK, they taught there. I grew up in that German Jewish liberal tradition, he said. And that’s why I came to Germany, to complete that circle of Jewish renewal. But I look around at the rabbinical conference here and I despair. I thought, he continued, in 1998 that there could be a generational change. But people warned me. My big mistake was in not realizing that change couldn’t take place because the only role models here were the previous generation. There is no real spirituality in Berlin; no prayer; it is a Judaism without God. He then explained his own congregational experiment, to see if there were enough Jews in Berlin to begin a community that would detach from the state tit and renew a practice of Judaism determined by individual commitment to a collective spirituality. It’s been very hard, he said. There is very little creative Jewish writing in Germany right now; there is no new German Jewish theology, no new ideas. So, in terms of your question, there is no critical mass here to counter the pressure of a Muslim presence. There are 200 Jewish births a year in Germany. So, say half of them are boys. That’s two circumcisions a week. No mohel can make a living doing two a week! And the Jewish butchers and bakers are slowly disappearing, he added. The disappearance of fresh food expertly turned out seemed like the final exhausted tap on the coffin of conversation. The rabbi rubbed his eyes. I could see the circles under them. It’s been a hard day, he said, maybe we can’t stay in Germany. We poured some more Tullamore Dew.