In his youth, Pier Paolo Pasolini had a recurrent fantasy of imitating Christ’s crucifixion. “To be condemned and killed despite being innocent,” he wrote in a diary entry during his mid-twenties which recalled his pubescence, “I saw myself hanging on the cross […] my thighs were scantily wrapped by that light strip and an immense crowd was watching me. My public martyrdom ended as a voluptuous image and slowly it emerged that I was nailed up completely naked.” His early sadomasochistic lust for martyrdom is probably not remarkable for a person who grew up in a deeply Catholic country, but it might shed light on why his complex political vehemence brought him as “many enemies among the communists as [he had] among the bourgeois.”

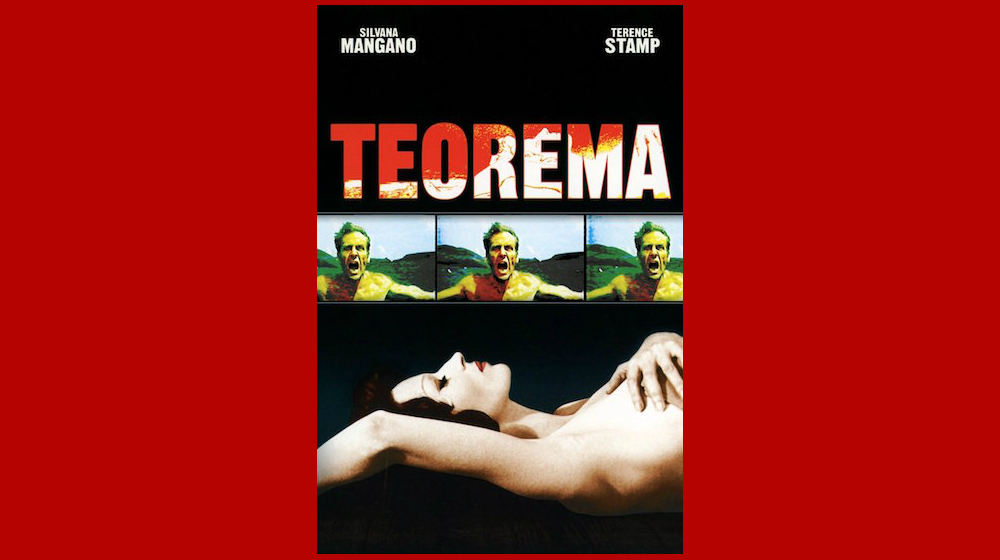

Half a century ago in September, 1968, Pasolini premiered his sparsely-dialogued, enormously influential erotic allegory Teorema (Theorem) at the Venice Film Festival, roughly seven years before his death. The polemical Marxist poet, novelist, critic, and filmmaker was brutally murdered in 1975, just weeks after finishing Salò, his film adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom.

In Teorema, an upper-class Milanese family is visited by an otherworldly Arthur Rimbaud-reading stranger whose sexual encounters with the mother, father, daughter, son, and maid have transcendental, life-altering effects. A fantastically eerie soundtrack by Ennio Morricone, with swathes of Mozart’s Requiem, gels the film’s disquieting tone.

Like its maker, the film drew mixed reactions from across the political spectrum. Many on the left abhorred its sympathetic critique of the bourgeoisie as humans suffering deeply unsatisfying lives. A Catholic film group gave it a prize for its undeniable “mystical character” before the pope himself condemned it. It was swiftly banned for running “contrary to every moral, social, or family value,” before finally being deemed a work of art. Parisians loved it.

Near the film’s beginning, parable is invoked through an over-acted angelic messenger who informs the family via telegram that a visitor is on his way. “The Visitor” (Terrence Stamp) arrives soon after without explanation, and exudes an immediate and captivating presence. Inheriting the propriety of the upper classes seen in Pasolini’s Kinseyesque documentary, Comizi d’amore (Love Meetings), Teorema’s bourgeois family initially repress sexuality by timidly acting on their desire for the ethereal houseguest. When the teenage son, Pietro, shares his twin bedroom with The Visitor, we watch as each undresses. The Visitor strips down matter-of-factly and gets into his bed naked. Pietro, on the other hand, is embarrassed by his own body and self-consciously removes his underwear beneath his covers. He puts on pajamas before saying “good night” and turns out the light. Unable to sleep, he tosses and turns, attempting to get up a few times, before finally going to The Visitor’s bed. He then slowly pulls the covers down and The Visitor opens his eyes and looks at him calmly, without fear. Pietro becomes terrified and shamefully returns to his own bed to sob. The Visitor then sympathetically goes to his bedside to console him by patting his shoulder. Later on, the father finds the two asleep in the same bed. In contrast, the religious servant Emilia runs to touch The Visitor. While he reads on a chaise longue in the garden, cigarette ash begins to fall onto his thigh and she rushes to brush it from his pants. Because of her peasant background, she’s able to recognize The Visitor’s sacredness, and is the first to have sex with him after he rescues her from a suicide attempt.

Two decades after filming, Stamp said he hadn’t noticed some of the film’s more provocative connotations at the time of shooting. In a scene where Paolo, the father, lies in bed immobilized from an internalized class malaise, Stamp noted “that the position in which I held him, with his [clothed] legs up on my shoulders, around my neck [to heal them], was one used by homosexuals in intercourse.” It wasn’t the film’s coded gay sex, its anodyne explicit sex, or male nudity that outraged so many. The problem was its transgression of the idea that an eternal conflict between flesh and spirit exists. Religious doctrine which insists that most expressions of sexuality are immoral has been naturalized through a cultural polarization of the sexual against the spiritual. In Western literature, writers like Herman Hesse, Christopher Isherwood, or Julien Green seem to suggest that this clash is a crucial component of the human condition, rather than a cultural construct used to control society. Camp filmmaker and author, John Waters, once quipped, “I thank God I was raised Catholic, so sex will always be dirty,” but anti-sex religiosity doesn’t only affect those of us directly indoctrinated by the church – it’s actually found pervasively throughout secular culture, for example, at the misogynistic roots of homophobia and in language used against women like “slut” and “whore.”

The notion that sexuality and spirituality are at odds stems, in part, from a heteromisogynist characterization of the erotic, and particularly of female sexuality, as debasement. In her seminal 1984 essay “The Uses of the Erotic,” Audre Lorde argues that because eroticism is a source of power within women, it is suppressed. “The erotic,” she asserts, “has often been misnamed by men and used against women […] made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation.” For her, a critical activation of the senses is necessary for intellectual work, like “writing a poem or examining an idea.”

One by one, The Visitor awakens each family member from his or her bourgeois slumber. By suggesting that the erotic can liberate one’s consciousness from the idles of consumerism — “a Fascism worse than the classical one,” according to Pasolini — Teorema collapses misogynistic anti-sex dogma. The sensual can be spiritual. Transformation and self-knowledge are accessible not by chastity, suppression, or self-flagellation (well, maybe some forms), but through love expressed as corporeal pleasure with an enigmatic stranger-saint.

The film remains controversial today because, in his metaphor of “divine love,” Pasolini breached another convention in an attack on the nuclear family and monogamy. There’s an overwhelming use of the verb “seduce” in analyses of Teorema to describe the sexual encounters with The Visitor, even though each person actually comes to the serene guest on his or her own. Behind the word’s connotation of manipulation is the cultural imperative that eroticism which does not confine itself within the institutionalized monogamous couple is malignant. Stepping away from dyadic notions of desire draws attention to the limitations of social constructs (monogamy, marriage, the family) and identities (heterosexual, homosexual) which rely on and perpetuate a conceptualization of eroticism chained to gender. Hence the duplicitous “bad” bisexual trope found in television, fiction, and cinema.

Many viewers had a myopic focus on the sex between male characters or on Pasolini’s same-sex preference. Critics called Teorema “a film on the difficulty of being homosexual” and accused Pasolini of creating an “auto-confession of the artist.” Just as happens today with films like Call Me by Your Name, a misreading of gayness was often made by an unwillingness to acknowledge The Visitor’s much more subversive omnisexuality. Neither gender nor age nor class are relevant to the eroticism of the story, which marks it as a rare piece of cinema. The film provides a template for an erotic imaginary which surpasses our culture’s dominant hetero and homonormativity. Like Rumi’s mystic idea of love, Teorema’s conception of the erotic lies somewhere “out beyond.”

Contrary to what many viewers in the late 1960s thought, Teorema is not a celebration of sexual freedom. After The Visitor leaves, Lucia, the mother (who appears to be in housewife drag, with drawn-on eyebrows and full makeup in bed) tries to replace the ecstasy she experienced by picking up young men for sex in their rented room or a countryside ditch. But, lacking an emotional intimacy, these encounters do not transcend. People were shocked to learn of Pasolini’s skepticism of contemporary “sexual permissiveness.” Much has been said of his frequently contradictory political commentary and severe anti-modernism (he hated TV and spoke against abortion and divorce), but considering what we now know, his distrust in “free love” is not so odd. He saw the sexual “liberation” of the time as false, the beginning of the commodification of sex. He later remarked that “the body had become merchandise.” He was right. There never was a sexual revolution. Most sex, in both how it was thought of and how it was performed — privileged straight men’s pleasure, as it does today. We’ve only just entered the nascent stages of a sexual revolution as we define what sex is not (nonconsensual), before inevitably joining Nicki Minaj in asserting one’s right to pleasure — to “demand that [women] climax.”

Pasolini was openly gay his entire career, and made no secret of his lifelong pursuit of working-class teenage boys. An early scandal forced him to flee from Friuli to Rome with his mother, and got him expelled from the Italian Communist Party, with whom he had a torturous relationship until his death. He once wrote that marriage is “a funeral rite,” and probably would have viewed today’s fight for marriage equality as an evolution of the false neo-liberation of the 1960s. As Barth David Schwartz explains in Pasolini Requiem, “the least attractive world he could imagine was one where homosexuals were like everyone else.” The undercurrent of eroticism throughout his life’s work recognized how deeply political sex is, and he was of the mind to disrupt (he stood thirty-three trials for obscenity, contempt of religion, and blasphemy among other charges), rather than become “the new normal”: a hygienic, palatable queer. After all, the security and comforts of normativity are a key value of the petit bourgeois, whom he feared the “whole of mankind was becoming.”

That’s why even with a newfound realization that their lives were vacuous and complacent before The Visitor’s arrival, the family in Teorema are unable to escape a vegetative existence when he departs. While Emilia, the maid, returns to her village to work miracles, eat nettles, and levitate, most of the family breaks down in despair. The daughter goes into a catatonic state and the son becomes a solitary abstract painter who urinates on his art — a bleak answer to the philosophical question of whether or not people can live without self-delusion.

The film’s ending is ambiguous. After giving his factory to his workers, Paolo sees a hustler in the Mussolini built-Milan Central Station and takes off his pinstriped suit, his shirt, his tie, and (yellow) underwear. The camera cuts to his bare feet which walk, not toward the hustler, but out of the station. In the final scene he is screaming naked into the sulfurous desert — a motif throughout the film. It’s unknown whether these are cries of desperation or redemption.

Ali Smith’s literary revision of the film, The Accidental (2005), imagines a much more optimistic outcome, and employs similar plot devices in a houseguest enacting transformations via sex and sensuality. A resplendent female stranger, Amber, disrupts the alienated lives of a middle-class British family with the idea that crisis precipitates much-needed change. In Smith’s feminist remake, Amber rescues teenage Magnus from hanging himself for his part in the deadly sexual humiliation of a female classmate. His path to self-forgiveness is reached not through the grace of a virgin mother, but via the defiantly-hairy vulva of a child-free woman.

Today, 50 years on, in a spiritually-bankrupt internet era of global consumerism and transactional Tinder romance, Teorema‘s portrait of sublime eroticism unburdened by sexual orientation, monogamy, or the double standard, remains a radical vision of the transfiguring power of sex. While we ready ourselves for the coming erotic revolution, as theorist Paul Preciado has said, “we must learn how to desire sexual freedom.”