Living today isn’t easy. Nor is living without trips to our local movie theaters. We miss them, and they miss us, and our pocketbooks, enough so that their future might seem to be in jeopardy. The influenza pandemic of 1918 is not just the closest touchstone we have to our current health crisis, but so too is its lesson about the resilience of moviegoing.

As I discuss in The Perils of Moviegoing in America (Bloomsbury, 2012), movie theaters have faced threats from various epidemics and closures resulting from them over the years, but none more so than in late 1918, when at a given point nine out of ten were shut down. Many exhibitors understandably questioned whether or not they would ever reopen. And when some of them did, they had to close down a second time due to — no spoiler alert — a second wave of the flu. The situation was grim, and, sadly, a number of theaters never recovered. But most did. Despite all of the revenue loss and the initial trepidation some moviegoers had about returning to them after the plague, they survived. The history is simultaneously bleak and tragic, and yet, in the end, encouraging and inspiring.

We want movies. And we want to go to them. Not just to sit at home and watch from our own screens, but to go to them.

Think about this story from 1918. A movie theater in Montana screened the last episode of the serial The House of Hate (1918) over and over again on the last day it was allowed to open due to the pandemic, literally until midnight, the striking of which meant closure. Local audiences crowded to see it. They had to see it. They had to know what happened next, certainly before they sheltered in place. And thus, we have further insight into the current and future fate of film.

Movie serials weren’t something you ate with milk, of course. They were episodic cinema, a chapter-per-week. Here were spectacles meant to keep you on the edge of your seat until their cliffhanger endings, leaving you hanging until the next episode. And your next movie ticket. In the 1910s, these serials appealed to adults and children. And they were popular — very, very popular. Consider the two following examples in order to conjure, to awaken, to reawaken, your cultural memory: 1) A would-be victim tied to railroad tracks as a train approaches her; and 2) A would-be victim strapped to a wooden log inching closer and closer to a revolving buzz saw.

The influence of serials on Hollywood films was profound, particularly their drive for near-continuous action. One critic claimed The Crimson Stain Mystery (1916) “starts off with a rush like a whirlwind and the action continues at top speed until the end.” And an advertisement for The Third Eye (1920) declared it was a “serial that moves with the swift rush of a tornado!” Here were masked villains like the “Clutching Hand” and the “Hooded Terror,” who planned to do bloody murder on good people. Some of these evil-doers even had world domination on the brain. They were supervillains before there were supervillains, before comic books, even. To end their reigns of terror required heroes of great strength and intelligence. The most popular were women, as evidenced by their very titles: The Perils of Pauline (1914), The Exploits of Elaine (1914), and The Mysteries of Myra (1916). Here were the likes of Wonder Woman and the Black Widow before Wonder Woman and the Black Widow. (Yes, indeed. Penelope Pitstop stopped many a bad guy in their tracks, whether railroad tracks or otherwise.)

But dangers came in many forms. In The Lion’s Claws (1918) — as well as so many others — wild animals did what they do best: go wild. (Lions and tigers and Joe Exotic, oh my!) Yes, indeed, the need to know, the necessity of knowing, What Happens Next. The episodic prevailed during the 1918 pandemic, as it continues to do a century later: Tiger King and WandaVision triumph, whether binged or watched a chapter-per-week. Cliffhanging has kept us sane, whether it’s watching the next episode of The Mandalorian or watching the next episode in the saga of the now-infamous Gina Carano.

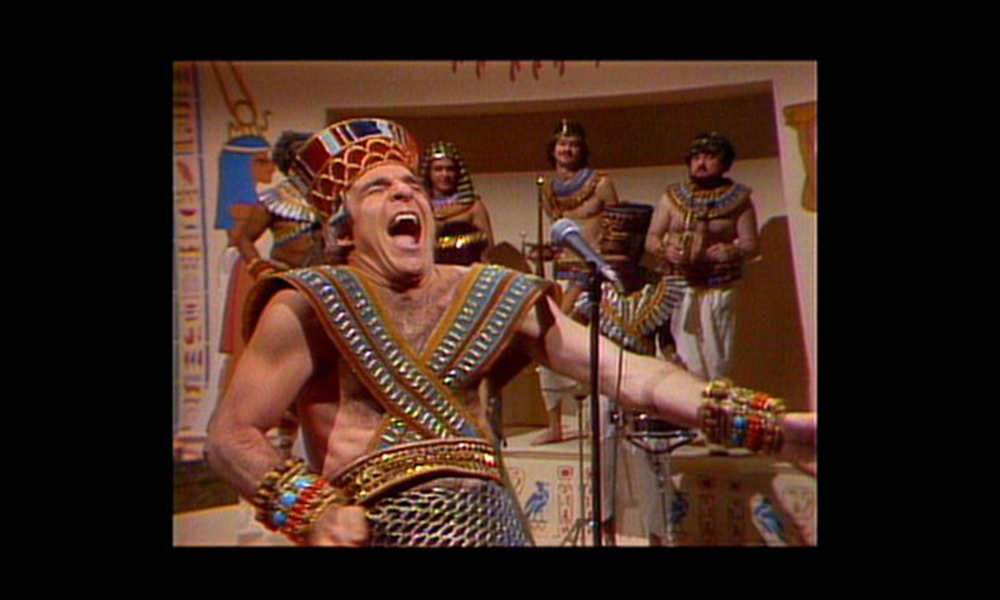

Oh, what’s that you say? We’ve learned how to do our cliffhanging at home? No need for the brick-and-mortar movie palace? “Tut, Tut,” said the King. And Steve Martin added, we need more than just streaming the small screen inside our “condo made of stona.” We need more than just cliffhanging, for that matter. We can get that from TV soap operas.

Without a doubt, we need the thrills and action and heroes and villains that stand literally 10 feet tall. We need to see and to hear what can only be seen and heard on the Big Screen, where cliffs really are larger-than-life cliffs, not just small bluffs. To do both home and theater viewing has been the norm since the rise of television. We could go out to the late movie and watch the late show at home.

And we will, because The House of Hate was just the name of a particular movie serial, not a description of the particular movie theater where it played. Besides, as popular as serials were once upon a time, the featured attraction was indeed the feature film.

We love our movies. We love going to see them, at the theaters we love. And we will again, over and over again, at a theater near us, very soon, and for a very, very long time. That’s truly what happens next, in our next exciting episode.