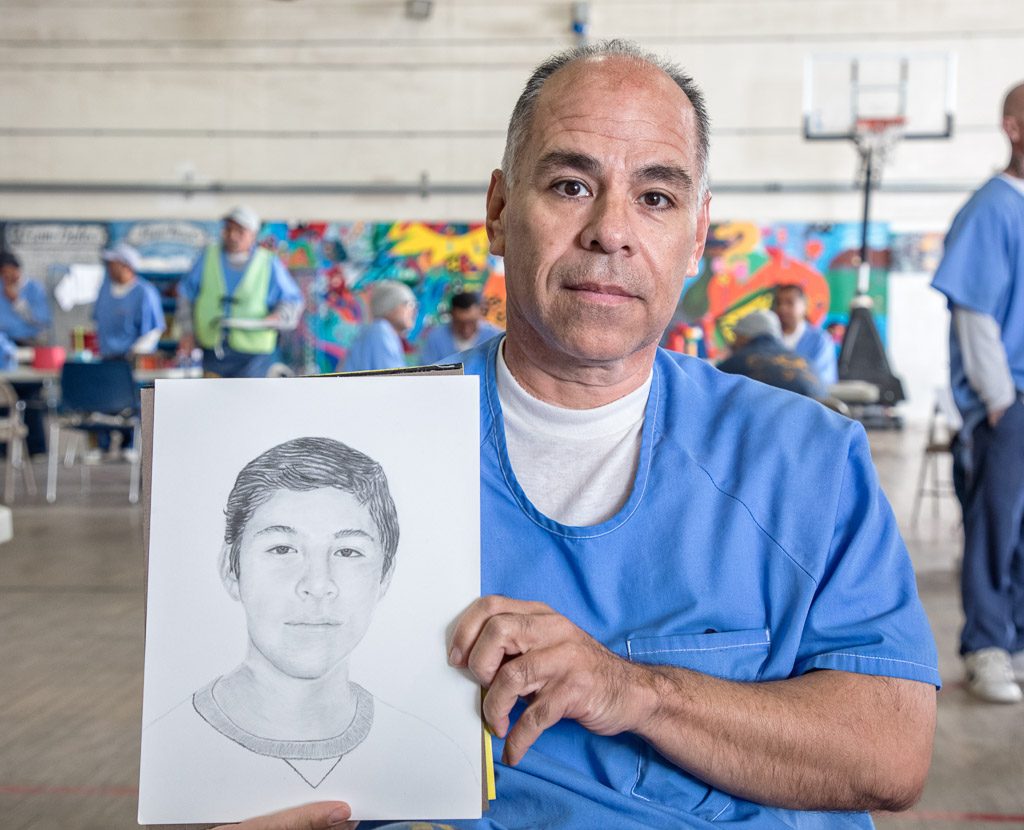

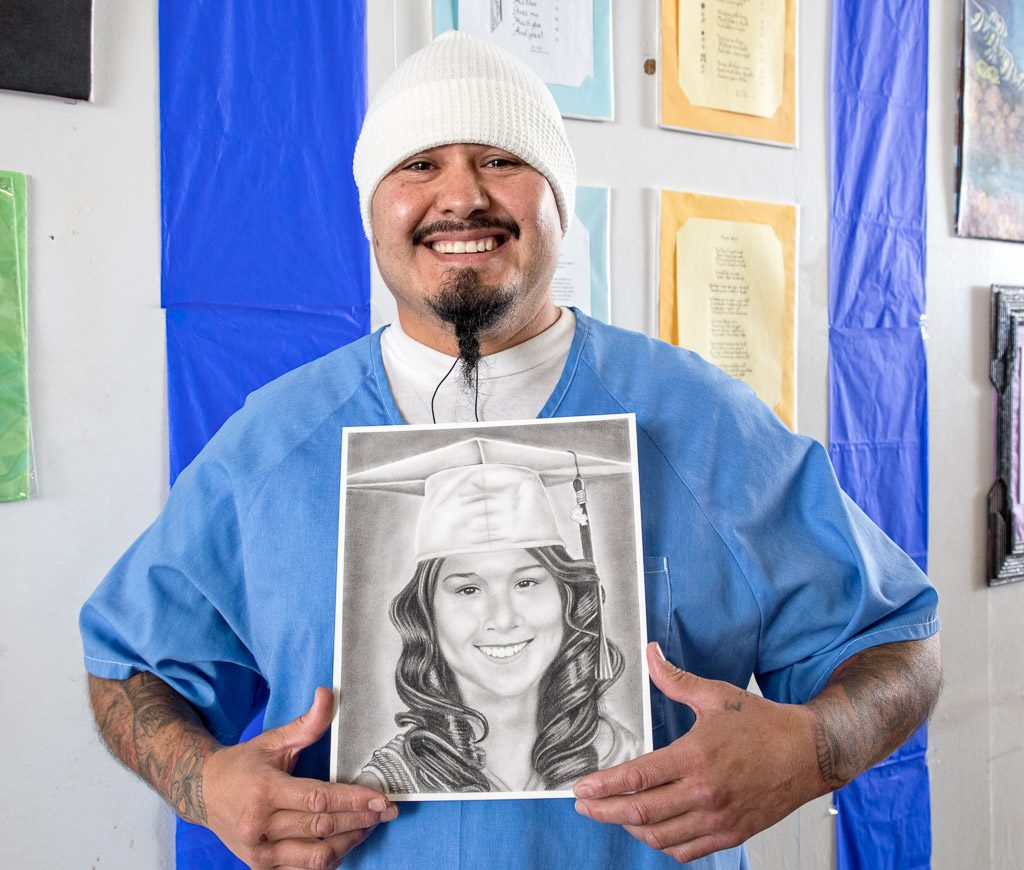

“It’s crazy how art can actually make you feel something.” I smile and nod. It is crazy, isn’t it? And yet sometimes — in the flurry of making and discussing, marketing and analyzing — we forget that primal aspect of art. But not here, never here: on the inside, where art is a lifeline like nowhere else. When I hear this comment, I am sitting with a group of men at a small table, one of multiple clustered around the large gymnasium. We are in a prison, one of four where I created and now oversee what has become an expansive and collaborative art program with 20 teaching artists facilitating multiple weekly classes in four prisons. At this table, we are looking at the men’s artwork and talking about their progress. One of the men, Shaun (all names are changed), has been with our program since the beginning and has taken nearly all of our classes. He recalls that when he started, one of our teaching artists looked at his colorful psychedelic drawings and said, “You’re an artist, man, you have to own it!” Shaun beams as he recalls this and proceeds to help the newer students look at one another’s art and express what they see.

There is something unique about being inside a prison when you don’t have to be there. I have been writing professionally for 10 years, and yet have never experienced the kind of writer’s block I did when reflecting on this experience and preparing to write about it. How to explain? Why? Because art can actually make you feel something. Being granted the unique opportunity to get to know and work with people that manage to survive and find hope in such a traumatic situation, one fraught with pain and guilt, is special. The artists and writers I work with have often been forgotten by society, and even by those that know them. And when they’re considered by a majority of people, it is often in judgment, and with a singular focus on crime. When I first started going to the prison, I was surprised at how the incarcerated people I met would say things like, “We are not all bad and evil people.” Of course not, I thought. But that is often how they are perceived — maybe that’s easier than acknowledging complexity.

One of the most incredible souls I know, Gregory Boyle SJ, founder of Homeboy Industries, puts it this way: “How would you like to be known only by the worst thing you ever did?” It kind of puts things in perspective, doesn’t it? We are all flawed. We are all guilty of something. It really isn’t any of my business what it is that any of the artists in our program are guilty of; what matters to me, and to the teaching artists and participants that I have the chance to work with, is the present and the art that exists, simply and wholly, in that moment — on paper or in conversation — What do you see? What do you think it means? How does it make you feel?

I began this work about four years ago as part of the Community-based Art initiative that grew out of my service learning class at California State University, San Bernardino, where I am on the faculty. I didn’t set out to bring art to people that are incarcerated and I don’t think I ever could have imagined that it would have had the impact that it has had — on me, on our teaching team, and on the hundreds of participants in our classes each week — when I started. But when this new student shared his insight with such infectious enthusiasm, I couldn’t help but smile. Art can make us feel — and grow and thrive and connect. I have always been interested in the way that art touches and bridges people, and in the parallel need to break down barriers in access to art, but in recent years, I feel more and more that this connectivity is all that really matters.

That’s one thing I like so much about my work in prisons: the experience inherently has the gift of immediately breaking down the hierarchies and extenuating circumstances that can complicate our relationship to art. It’s as if, when we walk through those multiple metal gates, each slamming shut behind us, cell phones and internet left behind on the outside, a button is reset. On the inside, as it’s often referred to by those in the system, art is a means to liberation. That’s true outside, too; I know from my experience as an artist and teacher that art can save lives. But to see its impact, over and over and in such a clear and unfiltered way, is uplifting and inspirational.

On the day that I hear the comment, half under breath, in awe, that art can make you feel things, I am there in my capacity as a mentor and guide. I invited faculty members from three universities, including ours, to serve as mentors to our participants. Most of what goes on in our multidisciplinary and collaborative program is more similar to what happens in art classes on the outside than it is different. Just as on a campus, the participants in our advising groups are a bit nervous and also kind of excited; they want to know how to succeed, how to graduate from this yearlong certificate program in which they are enrolled, and how they are doing. We go over the classes and check off what each has taken. They ask questions. We clarify. But there are differences from a college campus, too: the participants are dressed in uniform, and they each wear their label as an incarcerated person on their back. They have to get a pass to attend. The biggest differences are subtler and more profound. It’s like art class anywhere, but with all the meaningful stuff — the expression and communication, the sharing and making and interpreting, the breakthroughs and the struggles — amplified and thrown into sharp relief.

I take a brief break from my group to visit the music class, where the peer facilitators have asked to talk with me and want to show me how their classes have progressed. In that area of the gym, men are seated in three clusters practicing guitar, each led by a mentor. These three men approached me about nine months ago, asking if we could bring music alongside our art and creative writing classes. I said that I didn’t have a music teacher, and they offered to teach the class. So we talked and planned and now here they are, teaching peers.

I pause and look around the vast gym. Behind me, one of my university students leads a painting class in Spanish; she is assisted by one of our peer leaders, a young man who has been with our program since we started and took nearly every class before he asked to help teach. Next to them, an alumna from my program, assisted by a current university student brand new to our team, facilitates a printmaking class where the men look at art throughout time, learn the vocabulary of the discipline, and experience the magic of seeing an image revealed by utilizing the approaches to printmaking that our teachers have come up with using the limited materials allowed inside. Nearby, a group of men in a circle stretch themselves into Tree and Warrior poses, led by a new volunteer yoga teacher and one of our teaching artists. All around us, the cement walls are lined with murals. I have watched these evolve over the past four years.

When I return to my group, Shaun has engaged the newer artists in an animated discussion about their work. I ask him if he brought any of his pieces and he pulls several colorful drawings and collages out of his brown paper portfolio and lays them carefully on the table. We survey them for a while. The newest student looks at one bright compilation of shapes and imagery for a while and says admiringly, “Man, when I look at yours, I automatically see joy and wonder.”

About “Art Inside”: This project and my reflection on it are possible with deepest gratitude to the artists and writers that let me and our team into their lives and worlds while in such difficult circumstances. I am equally grateful to the institutions that support programs such as ours and all the staff that work with rehabilitative programs in prisons. The state of California recently reinstated Arts-in-Corrections, a unique collaboration between the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and the California Arts Council. Our university-based program began in 2013 with volunteers and internal grants and received an Arts-in-Corrections Demonstration Contract in 2016 that allowed us to continue and to grow. In addition to writing about the projects and people that I know, I will be writing about arts programs that I visit. I have sought and received permission from CDCR and the California Arts Council to document these projects. Because I have changed the names of the participants to protect their privacy, I will also change the names of all teaching artists, staff, and volunteers whenever feasible. Thank you to Peter Merts for allowing the use of his photographs of Arts-in-Corrections in this series.

Images by Peter Merts