Images by Peter Merts unless otherwise specified.

Eight-year-old B hid under the tables at any loud noise. If the classroom door slammed or the cabinet squeaked, he would leap up and crouch under his desk. On the rare occasions that he spoke, the soft monotone sound of his own voice seemed to startle him. This quiet boy, with a perennially downturned gaze and furtive eyes, was a student in my first class as a public school teacher. When his mother came to talk with me, she explained that she had brought her son here to the US to escape the war in El Salvador only to find another kind of war on the streets of Los Angeles. She and B lived next door to a house that served as a hub for a neighborhood gang and drug business. When I explained about the table hiding, she quietly volunteered her tragic story of intimate violence and trauma, observed by her son. It pains me still, more than two decades later, to think of this abuse and assault and the sensitive young boy crouching under a table while his mother endured it.

I was a young teacher just out of college and B’s story, though profound, was sadly not very unique among the narratives my young students carried with them. I didn’t know a lot but I knew from experience that art could transmute emotion. I gave B a journal and suggested that he draw in it whenever he wanted to express himself. To this day, my strongest memory of him is this lined composition book turned sketchbook. It was filled with page after page of open-mouthed figures, drawn with powerful dark pencil lines in a clear and confident hand. This near-silent and terrified boy found a voice through drawing and expressed himself powerfully.

My first year teaching coincided with the Los Angeles riots, which flared and burned directly around the school. Now my former students are in their late 20s, similar in age to most of the college students I currently teach. I haven’t seen B in all this time, but I imagine him having gone through high school and maybe to college, then into a job, utilizing his personal trauma as a source of strength to help others as a social worker or attorney or maybe to express truths about the human condition as an artist. While the optimist in me prevails and I still dream of happy endings for B and all the kids I taught, the realist in me sadly accrues evidence through the years of myriad ways in which the deck is stacked against so many kids like B.

¤

As greater awareness has built around the issue of mass incarceration, numerous groups and individuals around the nation have contributed — through dialogue and communications, programming and community building, lobbying and legal change — to seek and implement solutions to systemic injustices and oppressions. Over the past two years, I have had several opportunities to learn about these and to speak with people about the intersection of art and restorative justice. Our program holds panels to investigate this topic with leaders and practitioners in the field, including teaching artists, formerly incarcerated artists, and university students. These conversations explore the ways that the transformative power of the arts can impact and evolve individual and collective stories in the movement towards transforming the way we think about our embedded injustices in institutions.

Public education is one such system, one that I have worked in for nearly three decades. Several years ago, through a mutual friend, I met another artist and educator with a shared passion for expanding access to the arts. Artist Phung Huynh, now a professor of Art at Los Angeles Valley and the first chair of our Prison Arts Collective (PAC) Advisory Council, was part of a recent panel we held during the Freedom Festival on the campus of East Los Angeles City College. Huynh got at the core of the issue, stating: “There aren’t enough art programs. It has become a class divide, where people with money have access to art and art programs and those who don’t, don’t.”

Another panelist, Fabian Debora, once the longtime artist-in-residence at Homeboy Industries, who now teaches in prisons with the Alliance for California Traditional Arts, elaborated: “I believe that art is a universal language that needs to be reclaimed. Art is a language that allows homeboys and homegirls, the toughest of the toughest, to get into a vulnerable state. Art doesn’t speak and so it does not judge how vulnerable a person gets. Most importantly, it becomes a conversation, a dialogue that allows inmates to go back to their childhood to reclaim what was lost due to the impact of trauma. They can think about it, draw it, and then they can talk about it.”

The story of another panelist, Wendy, who took part in several programs in the arts while in prison, including our art classes, highlighted the ability of art to transform, transmute, and heal. Wendy shared, “As someone who found her bunkie hanging at 3:00 in the morning, art gave me a release and an area to go that kept me away from the cycle of the prison. Art was a space where I was allowed to find solitude and peace and relaxation. You can draw or paint, act or sing, and it can remove you from the realities of what prison is; anything that I did that healed me had to do with the arts. My goal is make mandatory arts in the prison system.”

Huynh added, “I can relate to the sense of art as a means of healing. I’m a refugee. My parents survived war and genocide but couldn’t talk to me about it. Art was a way of dealing with that; it is a way of making yourself visible. When I see participants in PAC classes smile and feel human, to be called a name instead of a number, that’s what it’s about.”

Of the ways that art can contribute to restorative justice, Debora added, “It’s a community effort; people always tend to blame mom and dad for the mess-ups of the child but the reality is that circumstances and the lack of opportunities where we come from are what influence some of the decisions that we make.” He expanded on how art can be integrated into healing and reintegration, “I’ve been a self-taught artist with no formal education. Art has given me a creative pathway and an opportunity to reclaim and exhibit my strengths, skills, and assets. As an artist, my responsibility is to continue to build these creative pathways [for others].”

One of our student interns, Alex, shares his thoughts on the intersections of art and the concept of crime as a community issue. In a panel we hosted at the Robert and Frances Fullerton Art Museum, Alex explained, “I was interested in the Prison Arts Collective because I do have many family members that struggle with incarceration and recidivism and I figured, if I can make a difference with the skills that I have, then why not do it? Art is a vehicle that allows people to discuss. I don’t think there’s any other subject or field like that, where it’s encouraged to disagree with one another and compromise and collaborate. Seeing that, and seeing our incarcerated participants talk to others that they wouldn’t have talked to otherwise, is really eye-opening to how thoughtful art is and what it offers.”

¤

More recently, I have taken this conversation behind the walls, asking incarcerated participants in our Arts Facilitator Training program what they see as the benefits and limitations of the arts in the realm of restorative justice.

I begin by asking if anyone knows what the term restorative justice means. As I have found with many terms and concepts that apply to a majority of our incarcerated population — at-risk, marginalized, limited access — a surprisingly few of them are familiar with the term. I start with the two or three hands that are raised. Typically, these are individuals that have learned the term in other programs, including Prison of Peace and Healing Dialogues in Action. They explain to the others that restorative justice sees crime not purely as an individual act but as an embedded community issue with an emphasis on healing for victims and the opportunity to make amends.

From here, we read a short text on the topic that comes from another prison program, the Victim Offender Education Group. It begins this way, “Restorative justice is a philosophy, a set of practices and a non-violent social movement.” The reading goes on to explain that restorative justice has a long history in indigenous cultures but is relatively new to the Western world, noting that it was utilized by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa at the end of apartheid.

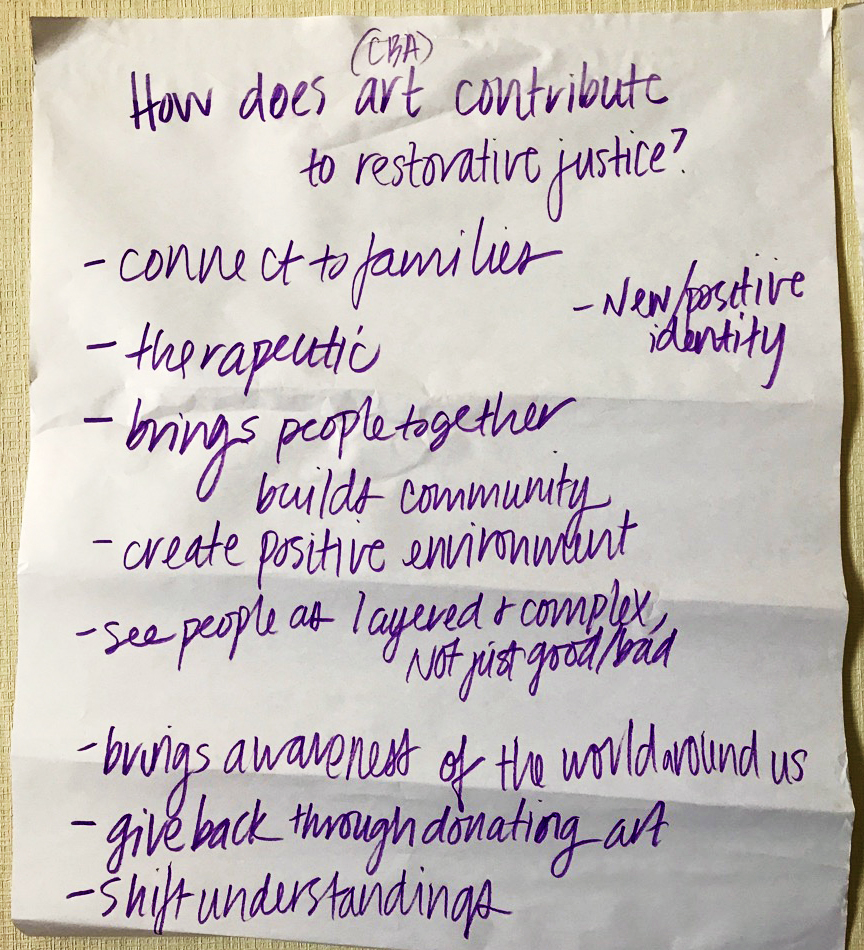

I ask the participants whether art can be part of restorative justice and we chart their ideas. When I ask this question of an incarcerated population, I am genuinely interested in their responses; they have a knowledge base and insight that I don’t share and I am curious to know what they think about it. Most often, they are enthusiastic and share a multitude of ways that art contributes to restorative justice.

The prevailing response is typically, “family connections” and “connecting to community.” These are often followed by “art is therapeutic” and “art promotes healing.” Another response that comes up often is the way that “art brings people together” and “builds community” both inside the prison and outside. Several participants share that they donate art to charities to “give back” and send art home to friends and family members to have a positive way to contribute. Others speak about art as a positive means to “guide youth and the next generation.”

The subject of shame comes up often and, with it, identity and bias. Students mention that art is a means of “personal transformation” and a way to create a positive identity. Many speak of the way that others only see them as “bad” and continually associate them with their worst acts. They often share a passion to change misperceptions and stereotypes of those that are incarcerated through art.

I also ask where art falls short, how does it not meet the needs of restorative justice. That chart is generally much shorter but, on a recent visit, it inspired a spirited conversation. One student, A, argued passionately that art could not do anything for his victims, that “a pretty picture” does nothing to ease their suffering and does not make communities safer. The others listen respectfully but several rebut the idea. J shared that funds from sales of art from prison could be used to promote victim awareness and public safety. Others express the value of connections they have reformed through art, with families and communities. When I offer that art does not put victims and offenders in dialogue, a few students rebut this as well, sharing that they have used journaling to directly tackle forgiveness and write letters of amends.

In one peer-led class, a former student in our Arts Facilitator Training regularly leads his students through creative writing and journaling that builds empathy and promotes healing and understanding. In another of the peer-led classes that result from this training, the teacher guides students how to connect interpretation in art with interpretation in life, guiding them to consider alternate interpretations of events from interactions with correctional officers to phone calls with family members. These approaches to art even more specifically integrate the tools and principles of community building and personal healing inherent to restorative justice.

¤

I don’t know what happened to B but I did have an experience recently that reminded me of him and rattled my persistent optimism. I was visiting our peer-led art classes at one of the prisons when a student in the drawing class looked familiar. I have been teaching behind bars for the past five years so this is not uncommon, but I couldn’t for the life of me remember where I had met him. He was a tall but slightly stooped, as if apologizing for his height, a black man with a gentle smile and ambling gait. I continued to make my rounds to each of our peer-led classes, sitting in as the newly trained facilitators led classes in drawing and creative writing.

The next time I passed by the drawing class he was attending, the man asked softly, “So, you still teaching at the university?” I nodded and explained that I teach in the institutions during the summer. The question didn’t provide much of a clue about how I knew him since most of the incarcerated participants know I am a college professor. He said he was in my class so I asked if he had been in our class here but left early. The he added, “at the college” and I immediately remembered him as a student in one of my classes at the university. I got chills and sat down. I told him it was good to see him again but that I was sorry to see him here. I realized quickly that I had to slow down, choose my words carefully. I wanted to be supportive but it would be hurtful to show that it was heartbreakingly surreal to see him in this other setting.

We spoke briefly about the art class he took with me — neither of us recalls which specific course it was, but we remember the experience — it seems worlds away now and, at the same time, familiar. I remember him clearly as an earnest but quiet student that seemed nervous, as if uncertain or surprised to find himself in a college art class at all. He remembers it as the only art class he ever took.

I tell him that I am glad he found the classes here and ask if he’ll be out soon. He shares that he has a long sentence, was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I ask about his family and he says they haven’t been around, expressing with empathy that they are disappointed in him. “They’ll come around,” I offer, but really, what do I know? Many don’t. And maybe they did for years and then stopped. Or maybe they were never there or are part of the problem. There are as many scenarios as people and there are also institutional realities — poverty, the bail crisis, systemic biases — but in the here and now, there is a student, our shared memory, and the detailed drawing that he continues to work on the whole time we talk. He tells me that he is making it as a card to send to his daughter that is about to graduate.