As of this writing, 49,169 people who are incarcerated in California’s state prisons have tested positive for COVID-19. This translates to more than half the total population of 94,848 testing positive for the virus since the start of the pandemic. Tragically, 215 of these individuals have perished from the virus in the past year.

Unfathomable waves of loss continue to unfurl in the wake of the virus, including illness, confinement, poverty, loneliness, and grief. Around the country, and the world, millions of people are confined to their homes to avoid the accelerating spread. The most fortunate among us are home with income and family, using spare time to bake bread, learn a language, or enjoy a movie marathon. Others are home alone or without work. Some are tragically homebound with abusers. One of the populations most drastically impacted by the pandemic are those confined to institutions, including prisons, where the contagion is most difficult to manage.

A year ago, I sat in my office on the campus of San Diego State University. I had been in that role for less than a year, so the office hadn’t yet acquired the comfort of familiarity. Like nearly everyone around the globe, I had been listening to the news, trying to understand the pandemic before it was named as such. I had spent many of the prior few days, and would spend more in the coming months, attending hastily called emergency meetings. The leadership at the university aimed to determine exactly how to continue operations while keeping students and faculty and staff safe, what it looked like to run a university in the midst of a global virus.

It was a Thursday — a date I won’t soon forget — March 12, 2020. I had about a dozen teachers heading to prisons across the state to teach art classes four days a week. Those who taught on Thursdays were likely just returning home. I had been trying to decide all day whether to continue our classes or pause them until we had clarity about the situation. Then I received an email stating the California State University was halting all non-essential travel. I still wasn’t sure what to do. What is essential? It’s a question many of us have asked ourselves more over the past year than perhaps ever in our lives. Was it essential to drive hundreds of miles to teach art in a prison? Was it essential to bring supplies to our team members who are incarcerated and leading their own arts classes after completing a teacher training? More broadly, was art essential? Was teaching? Was supporting students in prison?

I would argue emphatically yes to all the above.

Yet, having determined our task was essential, I asked myself, more profoundly, Is it safe? For our participants that are incarcerated? For our teachers? For the correctional staff? Could we perhaps unwittingly bring in a virus that could be devastating within the confined spaces of prisons? The question of safety was still difficult but clearer. No. It was not safe, not for anyone involved. The risk was too great. I sent an emergency email to all of our teachers and we started a phone tree follow up to be sure they got the information. We would halt our weekly arts classes on 17 yards in 11 prisons across the state as of March 13, 2020 until further notice. I remember with irony that I chose the word “pause,” a pause in programming. We are still paused. We might be paused for another year more. It is unclear. Like so much, it is unknown.

The Cell; Roy Gilstrap/Gary Harrell; cardboard, acrylic, cloth, clay; 12x17x6.5.

But what is known is that, despite the incredibly high rates of COVID among the incarcerated population and those who work in the prisons, the arts are still, and perhaps more than ever, an essential activity. So, for me, the question immediately shifted to how? How might we teach in a distanced way? The answer was more complex than that faced by university faculty shifting to online education. As difficult as the shift to virtual teaching was for students and faculty — and I cannot overstate the challenges of it — the shift in the prisons was much starker. Students in our arts programs do not have internet access. They were not allowed to gather in small groups to learn from trained peers. Our only avenue for teaching was to mail lessons into the prisons. So we got busy figuring out how to translate our active in-person arts classes to paper lessons.

In the first weeks, we weren’t sure if funding would continue. Our colleagues at the California Arts Council advocated for the arts programming to continue and were given the green light by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which has in recent years put an emphasis on rehabilitative programming and education. For those who haven’t taught in prisons, the layers of rules and regulations that it takes to teach a rehabilitative art class in prison are daunting. But, soon enough, our team began to navigate the emerging set of rules and complexities that governed sending distance learning packets into 11 institutions, each with its own set of rules and guidelines. Some allow a self addressed stamped envelope for the participants to send back their lessons; others do not. Some only allow metered mail (stamps can be a form of currency in prisons). Some would let us send directly to students while others required that we mail lessons to administrators who would review and deliver them. Each packet had to be emailed to staff for review ahead of sending. None of this was a surprise but all of it was new. On top of that, the correctional staff who supported us in approving and distributing these packets found themselves in an extremely difficult situation, many still on site in institutions with rising virus numbers and others, like our teachers, working remotely from homes with varying degrees of readiness to become offices, with children or grandparents or pets competing for attention.

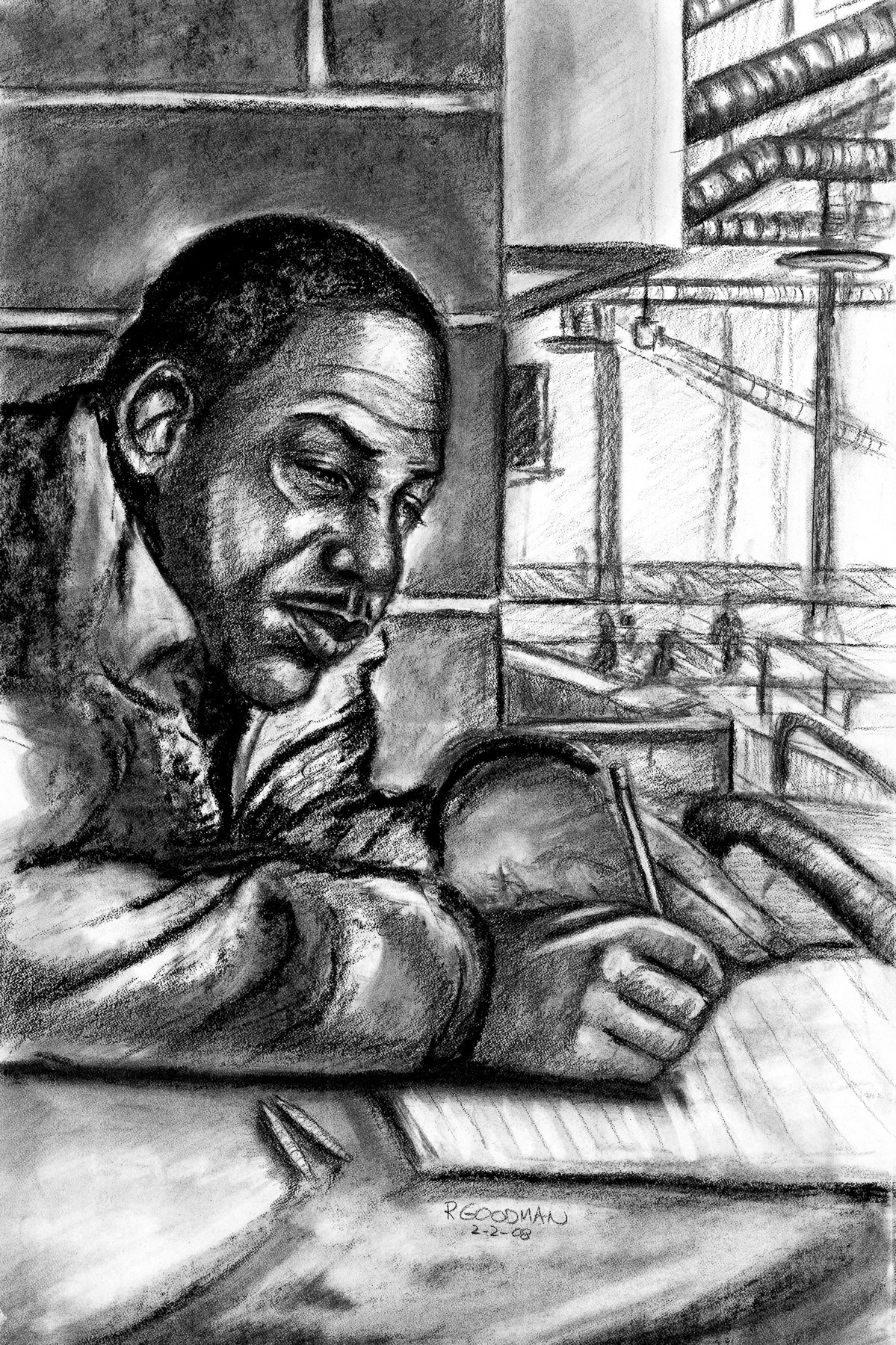

Untitled portrait by Ronnie Goodman, charcoal, 2008.

I admit that our first packets were less than perfect. Each of our dedicated teachers did their best and our administrative team maneuvered the baroque set of regulations to send them, but we had never done this before. We forgot to add page numbers and some of the participants got lost reading the stack of lessons that arrived at their cells in manila envelopes. We hadn’t fully accounted for the fact that many of the participants have less than a high school education and distance learning is ultimately made up of words on paper. In those early days, we presumed that this might last until summer. Our teachers wrote out lessons to complete the numerous classes in visual art, yoga, and art appreciation that had been in progress across the multiple prison yards.

We sent them off and waited for feedback, which was a long time coming. By mid-summer, the mail started to trickle in at our university address. The participants’ gratitude that we “remembered them” was profuse, both heartwarming and tragic as it reminded us of their plight. It soon became clear that we needed to retool the lessons we had sent. We added more images and activities, included graphics to indicate which pages to send back, shortened the text, made word searches and puzzles for the vocabulary. We brainstormed how to help them to create a mindset for creative arts practices when they were in lock down in a prison during a pandemic. How, we wondered, might we encourage a reenactment of the safe space that is so vital to our in person classes for individuals locked in cells with a spreading virus?

This brings me back to the question: What is essential? Is art essential? Is it a good use of time, energy, and funding to make distance learning art packets to send to people imprisoned during a deadly pandemic? Again, I say emphatically, yes. Is it perfect? No. Is it an ideal art class or modality? No. Do we wish we could do better, connect with our students via Zoom or phone? Of course, even despite the new complications, it would make the classes more accessible. But this is what we have access to now, packets made collaboratively by a team of teachers and interns, printed and mailed with a small bag of art supplies (pencil and eraser, a few colored pencils, sometimes watercolors). This is what we can do. Is it helpful? Is it enough?

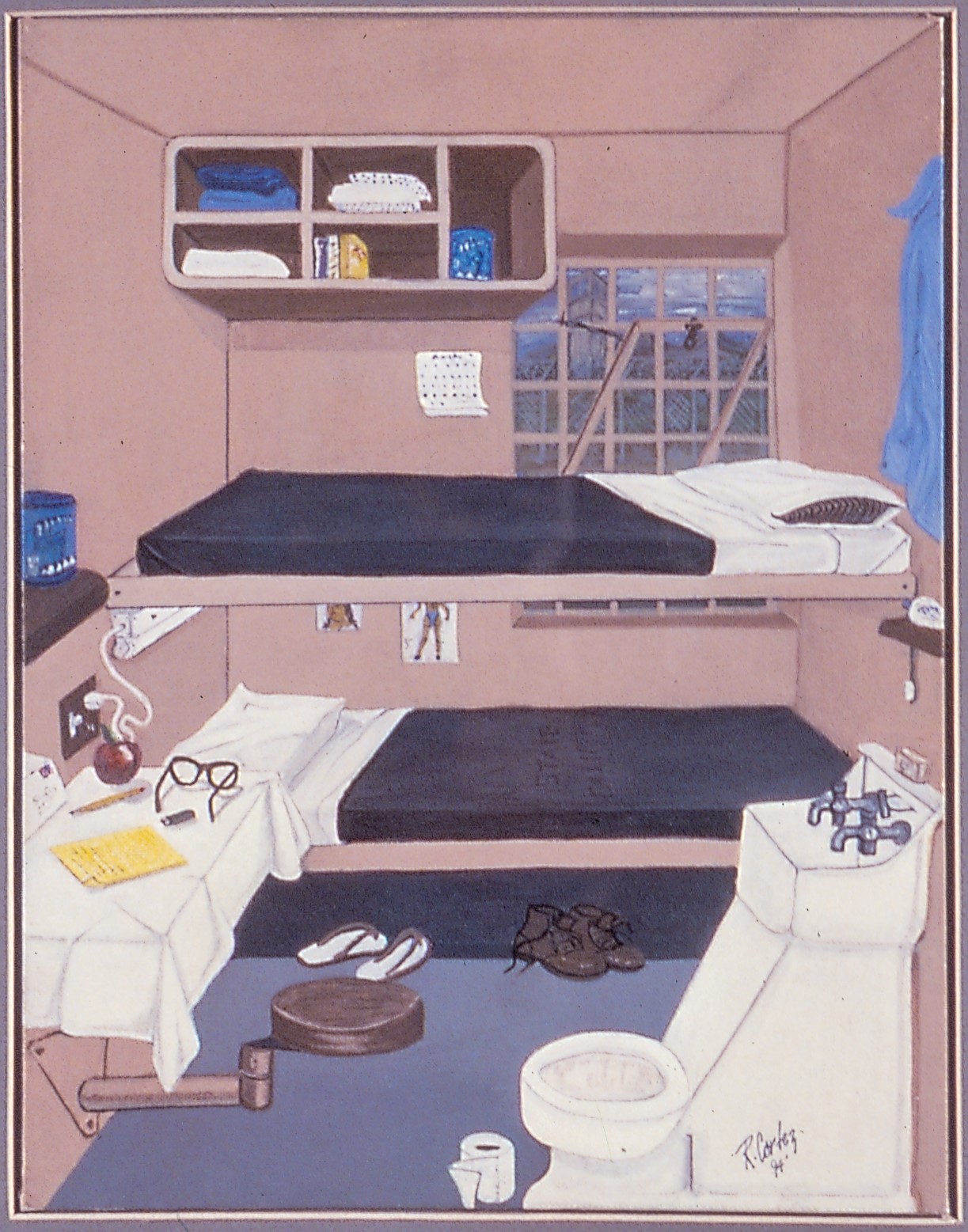

My House; Roy Cortez, painting, CTF Soledad, 1994 (William James Association archives).

Art is an outlet. Art is expression. Art is communication. Both before and during this pandemic, art has been a means for all of our team, me included, and our participants who are incarcerated to connect — with ourselves, with one another, and, for our participants behind the walls, it was a also a vital connection with the outside. Even if each of those is limited, and the last drastically curtailed, the significance of the arts remains. Art connects us, even and maybe especially during a frightening time. It has now been one year since our “pause” on in person classes. Everyone is getting tired. Some team members have moved on. Happily, some of our participants have reached out to let us know that they were released.

Meanwhile, our skills and ingenuity at distance learning have improved. We have collaborated with colleagues across the state and nation, even across the world, to share ideas and hatch plans to make the distance learning packets the best they can be. Many teachers that used to guide students in person have learned to navigate a digital landscape, write how-to guides, determine copyrights, and more. We have sent in over 2000 packets to hundreds of people in the prisons. In addition, our team made a series of instructional videos in art and yoga that now play in all 33 California prisons. With the ingenuity of a new volunteer, we started a radio program that plays on KSPC so that our participants in the prisons in Chino can, if they happen to have access to a radio, listen to interviews with artists, writers, and musicians who, like themselves, were in prison but are now free. It felt like a sign that something was working when a student inside wrote that he had heard our radio show featuring an artist he had been in classes with in the prison who had released. He was inspired and hopeful to hear of this man’s transition.

The mail continues to expand, with more of the lesson responses coming back to us every day. Our participants send sketches from the lessons — such as posters about social issues, like bullying and recidivism — and their thoughts in response to reflection questions in each lesson. Sometimes, they include their own little sketches, a cartoon of a square faced man hopped up on coffee with the words “must draw,” a poignant pencil sketch of a cell, the artist’s only view day in, day out, or a funny face drawn on a feedback form. They share that they have learned the point where two parallel lines meet, how to draw an elephant, that contemporary art has heart and meaning. They reflect on their identity and reasons for making and teaching art. Is all of this essential? In a deadly pandemic, does it matter that someone can draw an elephant or interpret art? In a word, yes. One student shared, “Oftentimes, using our imagination and creativity, it would seem, is the only escape from our physical and social isolation.” Another said simply, “The experience made me feel like a part of something.” This might be the most essential role of art during a deadly pandemic.

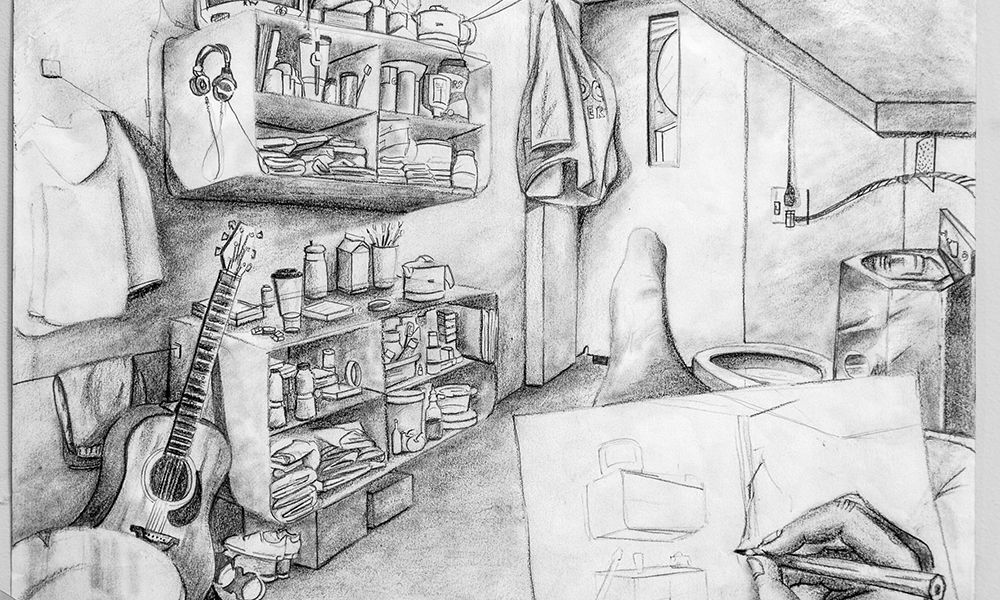

Top Image: View of my Cell; Anh “Ben” Nguyen, pencil drawing, 2014.

All artwork photographed by Peter Merts.