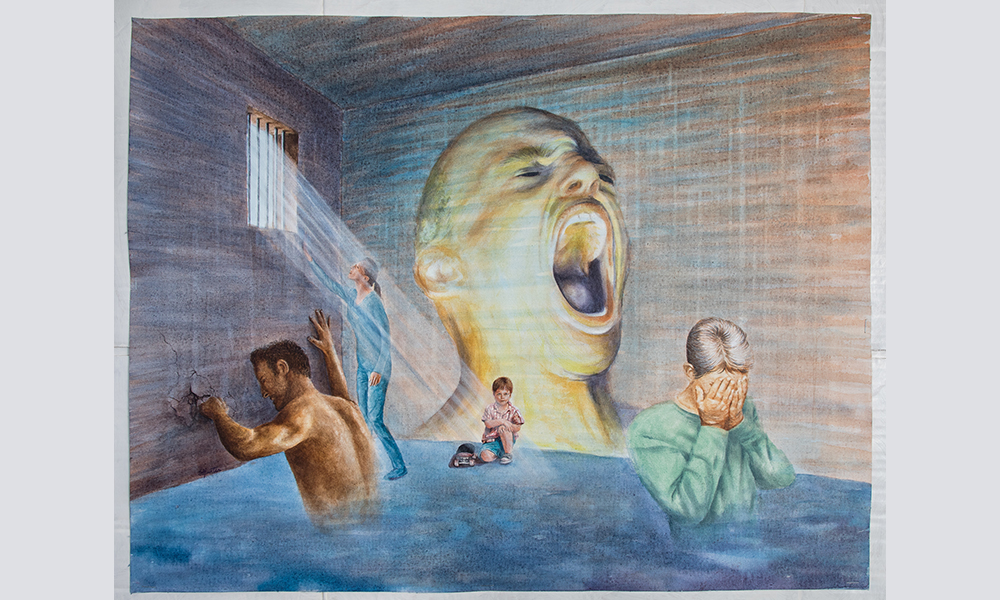

Top image: drawing by Stan Hunter, 2017.

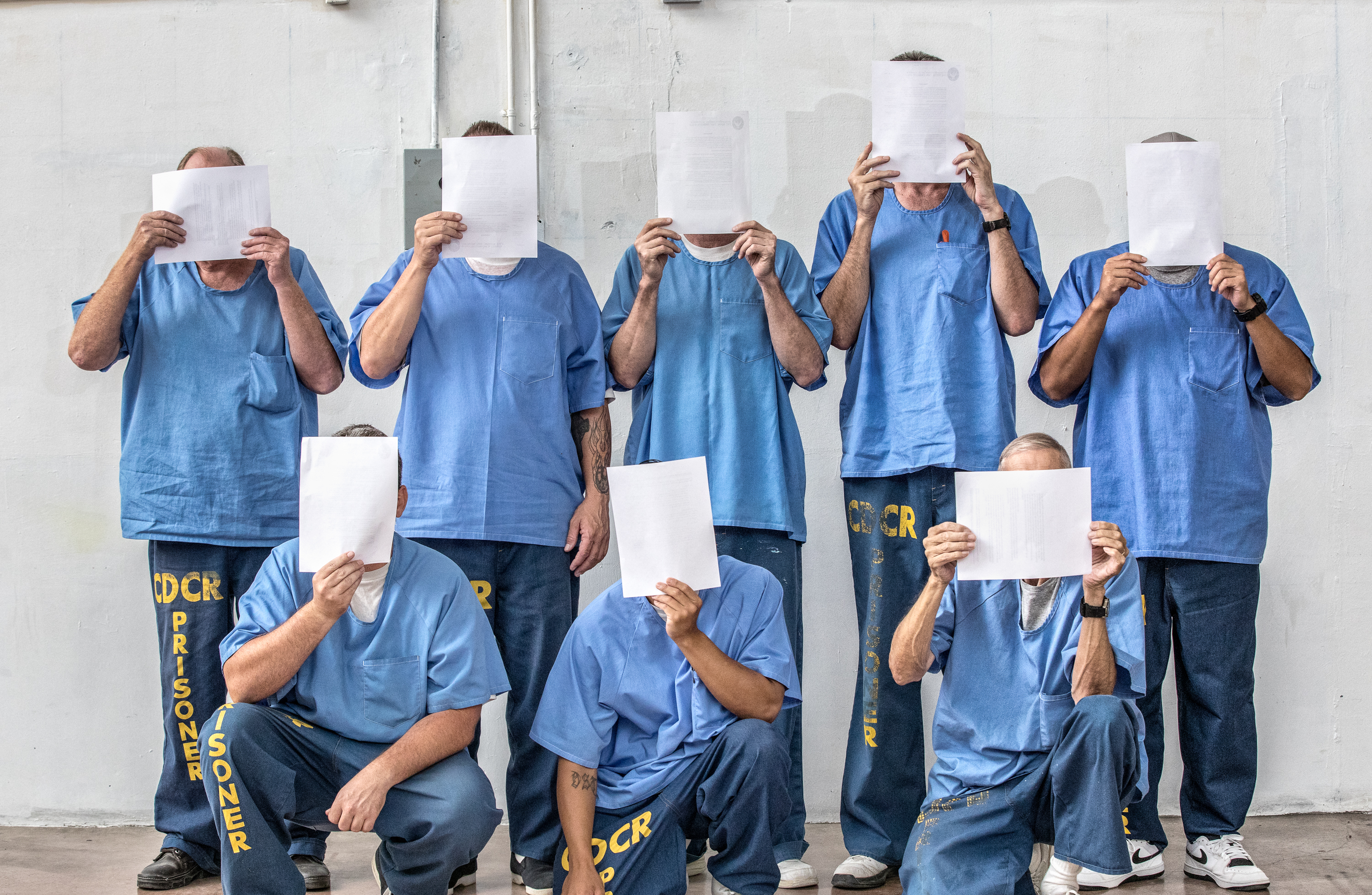

All photos by Peter Merts, courtesy of Arts in Corrections.

It was the last day of our six-month art facilitator training program at a maximum-security prison for men. We were scheduled to have a graduation ceremony that week and everyone was excited. This particular program had begun with a deep sense of desperation. Ours was one of only a few programs at this prison and the library had been closed for months. The men sensed the lack. Interestingly, this was also the first prison in which I had a student in class that had attended the first school where I taught. Luis hadn’t been in my class, but meeting him here, talking about the same teachers and students, was both uplifting and deeply sad. I was glad to connect, but not here, in this place. My first year as a teacher was 1992, the year of the Los Angeles riots. Our school was located in the middle of deep unrest — fires and looting and anger. Luis and I each remembered that unforgettable school day when riots broke out around us.

This was also the prison where our class was interrupted more frequently than most. More than once, correctional officers entered and stated calmly, “All free people outside.” The phrase is raw and shocking out of context. It is surprising the first time you hear it inside, too, and then it becomes strangely familiar, a reminder: We are free. And they are not. When called to do so, we waited patiently outside the classroom as officers swooped across the prison yard. Our teachers coughed as tear gas tinged the air from the next yard over. We peeked in the windows of the classroom and waved at our students, who smiled and tried their best to make the situation less weird and awful than it was. I was relieved they were allowed to sit in their chairs. Sometimes the incarcerated population must lie face down on the ground if there is a disturbance in the institution.

A mural painted by inmates, in an exercise yard at Pelican Bay State Prison.

When we were able to go back in the classroom, the students always apologized, as if there were anything they could do differently. They were sorry that we experienced this struggle, sorry that the stark line between us had been writ large for a time, sorry if any of our team felt afraid or nervous, sorry the class had been interrupted. I used to think it was odd that they apologized and brushed it off but then I have realized that it was the kind of apology you offer a dinner guest if something upsetting occurs. Even if it’s outside your house — a helicopter overhead or loud neighbor dog — you apologize. Even though they were captive here, this was their home and they wanted us to be comfortable.

From these challenging early days, the class had grown into a special opportunity to collaborate among creative peers in a highly restrictive space. At first, some of the men didn’t even know why they were in the class. Others thought they were going to learn guitar or poetry. Once we explained that they would learn to teach, many got nervous. But over time, the students had come together to help one another learn to develop lessons, teach a class, and most importantly, cultivate community. Now they had completed their 60-hour training, their challenging final project, and were ready to graduate. We worked with the institution to secure a space for the event. We invited members of the administration to attend and were thrilled that they allowed us to bring in cupcakes from a local store. It might sound trite, but in six years of programming in prisons, this was the first time that we had been allowed to bring in celebration cake from the outside. A few times before this, the institutions had supplied cakes or pies baked in their culinary services for our events, but it was special to bring one from a store.

The day before the ceremony, we gathered to prepare for the graduation. The students elected representatives to share portions of the art lessons they had taught to the group as their final project. We wanted them to demonstrate their abilities as artist facilitators. We practiced multiple times. Everyone was nervous but we were ready. In the hotel that evening, we signed the certificates, counting twice to be sure none were missing and double checking the spelling of each graduate’s name. We wrote to staff to ensure that the invitations had gone out to all the administration. And we drove to the market to get a specialty cake, piled high with sugary icing and decoration in the colors of our program logo. The front desk attendant let us store it in the hotel refrigerator.

Painting by incarcerated artist in a visiting room at RJ Donovan State Prison.

The next day, we made our way through multiple prison gates and across the dusty yard to the visiting room where the graduation event would take place. The participants arrived shortly after we did, one by one, through a locked door on the side of the visiting room. An officer checked each one off a list and took his ID before he could enter. Everyone seemed cheerful and eager for the celebration to start and everyone helped get the room set up. Some men brought handmade posters they created for their lessons so we taped these to the windows to share their work. Others brought paintings and drawings, which we laid out on tables for guests and peers to review. We arranged the chairs in rows and laid a plastic baggie with markers and pencils on each chair in the back row, where our guests would sit. We were ready.

It was a Friday. I remember because Fridays are a day in which many prison staff wear red in honor of the military and our veterans. Right before we began, a group of prison administrators and staff arrived, right on time. Most were dressed in red polo shirts and slacks. The shirts were a shift from the typical khaki officer uniforms and dark suits on administrators. It was somehow more relaxed and cheerful. The group of staff was larger than had shown up at any of our previous events. It looked to be a great day.

I welcomed everyone to the event, explained our program, and introduced the participants that had been selected to teach a section of their class to show what everyone had learned. It was important to us that the guests participate in the projects. We wanted them to see that the men had learned to teach and experience the unity that comes with creativity. Ron started us off. He was a little nervous but proudly shared his lesson about adding shading to drawings. He invited the staff to take a pencil out of their bag to try it. A few did. Most did not. It was fine. He continued and everyone listened politely. The lesson went smoothly.

The next facilitator stood up. Angel was going to teach a project with colors. He asked the guests to get out two markers. When only a few followed along, he applied what we had learned in class about teaching and gamely encouraged the guests, his students for the moment, adding with enthusiasm, “There are no mistakes in art.”

At this point, one of the higher placed administrators raised his hand. A little nervously, Angel called on him. “Yes, I would like to say something,” the officer said loudly. He stood up. He was a tall and imposing man, even with the red shirt in place of a correctional uniform. “We aren’t going to do this,” he began. He cleared his throat and continued. “We aren’t going to use these colors. We aren’t going to draw these things with you. We are here, and that’s how we show our support, by showing up.”

It wasn’t necessary but seemed reasonable. We knew that, under normal class circumstances, the officers have a job to do and cannot participate in the class in any way. We had hoped that they might take part in this limited way as members of the audience but understood if they couldn’t. That’s when things turned. The officer did not sit down. He straightened and continued, “We’re over here, and you’re there. There is a line between us. It’s a line we can’t cross. That line divides us and keeps things safe.”

The room fell quiet. Poor Angel did his best to finish the mini-lesson after that. As a first-time teacher that had literally just finished his training program, it was a big ask to teach after that statement. It hurt that he had to do it but he met the challenge gracefully. I was glad that our next and last presenter was Jonah, a wry and witty creative writing teacher. I knew that he could handle facing this room filled with heartbreak. The division, the lack of humanity, we had worked so hard to ease throughout the class had been writ large by the officer’s comment. In that moment, the raw truth was exposed and it cut into the unity we had created. With full recognition of the pain elicited among the graduates in the room, Jonah taught a short lesson in poetry and throughout found ways to make everyone laugh. That laugh was good teaching. It showed his leadership and allowed everyone, staff and students, free and captive, to recognize our camaraderie. It erased the line. It brought us back together. I was proud, impressed, and moved.

Next on the schedule for the day was the distribution of certificates. Everyone in the room applauded as each man’s name was read. When it was over, we thanked everyone for coming and invited the guests and graduates to have cake. Our team donned plastic gloves to cut the cake. Not having done this before, we asked some of our participants to wear gloves and help pass cake to the guests. To our surprise, one after another, they demurred. One of them finally came up to me and quietly explained, “We want to help but you should give it to the staff. They won’t eat it if we give it to them.”

The cake had seemed like such an accomplishment when we were given permission to bring it. Now it only highlighted the separation further. We continued to pass the cake and most graduates ate some. They were much quieter than usual at a celebration like this but politely thanked us for the cake and congratulated the presenters. Most of the guests, in red shirts and khakis, a few in dresses and one or two in suits, graciously stayed to look at the art so carefully arranged on the tables. Not many took a piece of cake, even with our team passing it. But they enjoyed the artwork and posters and commented at the talent among the group. Most of them talked to one another and did not acknowledge the graduating students, who stood quietly several feet from the tables with the art. One or two of the guests asked to meet some of the artists to personally tell them that they liked their work. I was more than happy to make the introductions and appreciative of this gesture. But overall it was a strange afternoon.

Members of a Prison Arts Collective workshop at the California Institution for Men explore issues of identity through art.

Their graduation from the facilitator training had been a success but the officer’s comments had stripped something from it, cast a shadow on the event. He didn’t say anything untrue. Yes, the men were in prison. And yes, we knew that there were barriers and rules. But the class had offered a way out, a way for the men to see themselves as something other than a prisoner — as a man, an artist, a team member, as a teacher, as valuable. The day was a celebration of accomplishment and hard-won effort, not only of the content learned, but also of relationships formed and a sense of self rediscovered. Hearing those words, true or not, cast a pall on that accomplishment.

I always knew that, as soon as they left the space of the class, our bright, creative, dedicated, kind students returned to the cold reality of prison. I had visited their living quarters and chapels a few times but I had never heard the stark divide that marked them day in and day out articulated quite so bluntly in such a setting. I had experienced the line literally, from the side where I stood, when our students were strip-searched before class or, less distressingly, as our art supplies were dumped out and counted one by one, but this was different. I had not felt the invisible line quite so palpably or emotionally.

I knew that the officers had come to support the men and our program. I was pretty sure that the officer who spoke up had not meant any harm by the comment. I think, maybe, he felt that he was clearing the air, trying in his own way to be supportive. But that’s not what happened. When the staff left, the men seemed deflated. Some took it better than others. Jonah brushed it off. Everyone told Angel he had done a great job. But some of the men expressed their discouragement that these comments had been made.

“That’s how they are,” one said, resigned.

“That really changed things,” another shared.

“Why’d he have to say that?” Luis asked. It was a good question. Why exactly did that administrator, an officer who had all the power and control in the room without saying a word, feel compelled to express it verbally at that moment, rather than simply leave the baggie of art supplies quietly on the chair as other officers and staff had done. The psychological dividing line had been writ large and was impossible to un-see.

Prison might be the most extreme example but these lines between us exist throughout society. Our laws and institutional structures operate on assumptions that some people are more worthy or good or deserving of safety than others. This is wrong. This is not true. On a good day, I can see that this belief is based on bias, implicit or explicit, and long-adopted norms. On a clear day, I also see that it’s not that simple. Regardless, it’s time to change. It’s time to break down the barriers that mark some groups as “us” and others as “them” and see that we are and only ever have been we. It’s not just time — it’s long overdue.

“The Cell”; Roy Gilstrap/Gary Harrell; cardboard, acrylic, cloth, clay; 12x17x6.5

Back in 1992, when I was a new teacher, my students taught me so much in their youth, resilience, and wisdom. On that surreal day in early May, by 10:00 a.m., my third graders were saying “Huele humo” (“It smells of smoke”) as fires burned all around our school. Luis may have been in the class next to mine, or down the hall, a young student trying to understand why the city around him burned.

I am an optimist. I am hardwired to believe things will change for the better. But I no longer believe this will happen without radical rigor, and even with that it’s getter harder all the time to believe in change. It wasn’t fair for Angel to address that room after the painful division was demarcated. It isn’t okay that Luis, a bright kid in a poor neighborhood, and so many others like him lost their youth and their freedom. It isn’t right for those that have lived under this weight for so long to bear it alone.

It’s time for us to reimagine the way we consider one another, who is valuable and deserving. We have to redesign the way resources are distributed so that my third graders from back then, and all the others before and since, have the same access to books and laptops and art supplies as any other kid. We have to recreate the way we teach so that the first time a student learns about a black artist isn’t during March and the first time a student reads a feminist theorist isn’t in a women’s studies class. We have to reengineer the healthcare system so that the weight of a global pandemic doesn’t fall with such ferocity on the shoulders of individual doctors and nurses, and on communities of color. We have to remake the justice system so that the students in classes at prisons reflect society at large instead of being comprised overwhelmingly of people that are black and brown and poor.

It is incumbent on all of us to stop these invisible lines that divide us, from the concrete walls and metal gates to the more insidious barriers around our hearts and imaginations. We must stand up to demand and create change from the inside out. I see the crowds protesting injustice around the world today and I think, maybe this is it. Now is the time.